Nineveh and Its Remains

Volume 1

By Austen Henry Layard, ESQ. D.C.L.

Part 1 - Chapter 10

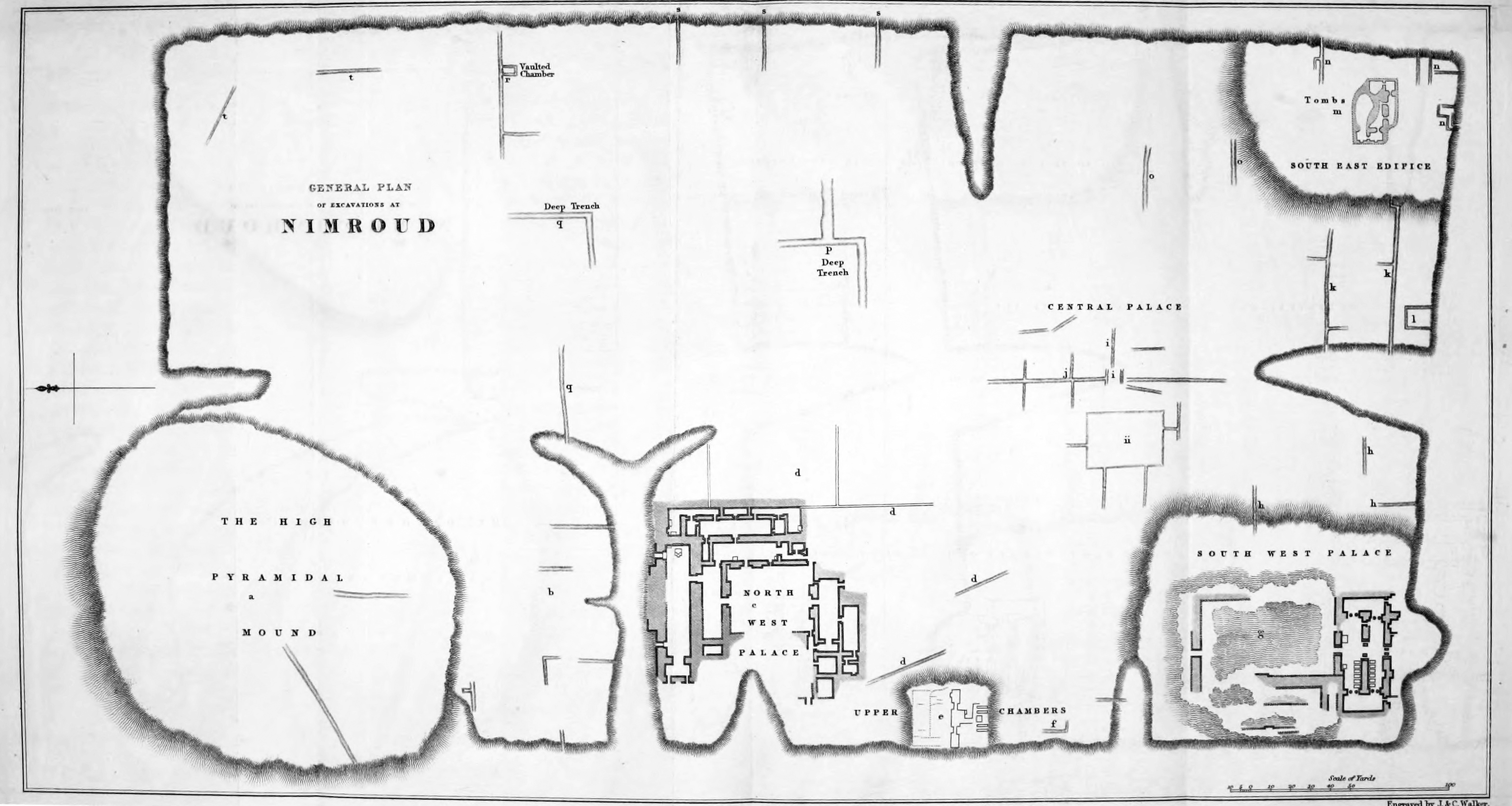

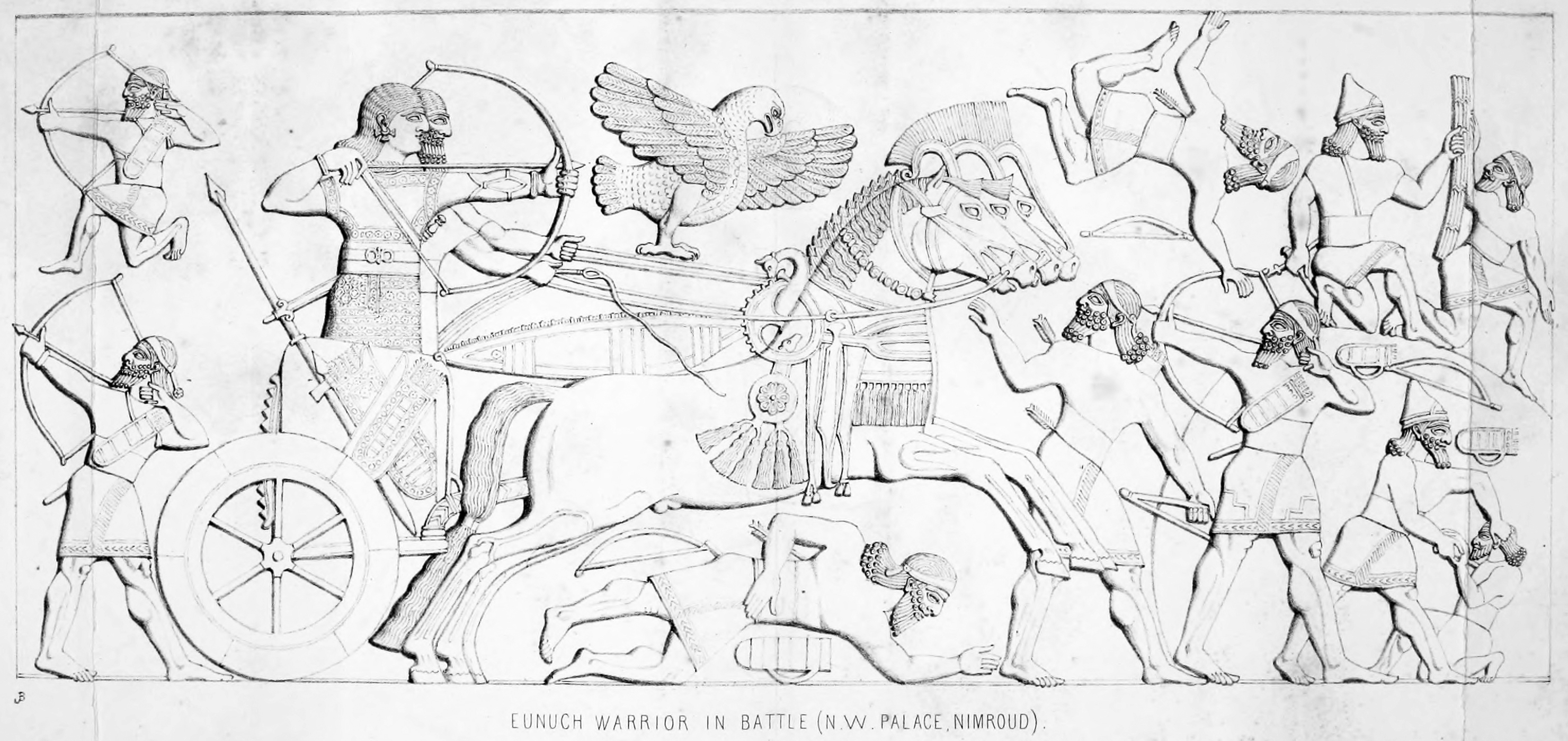

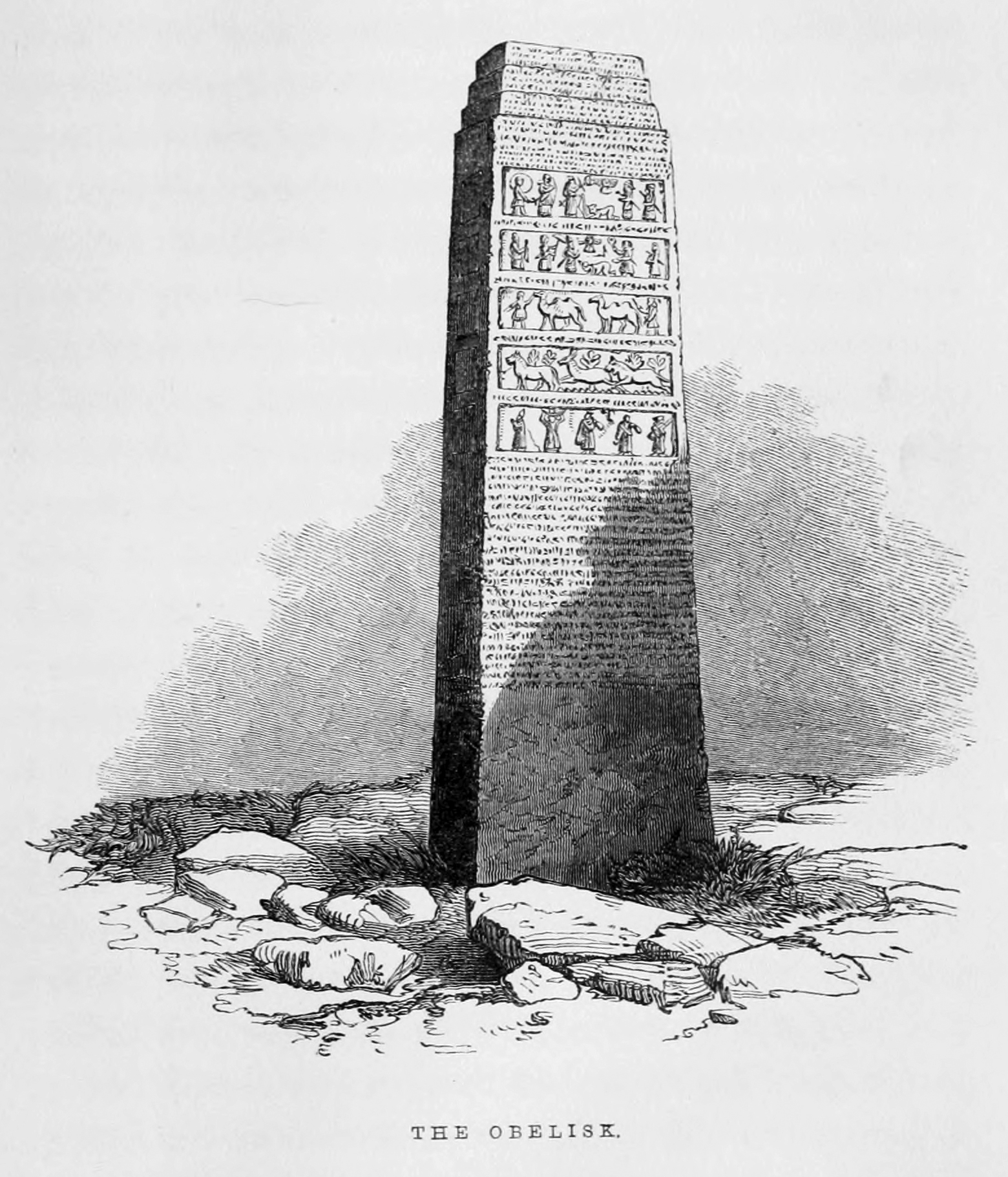

On my return to Mosul, I received letters from England, informing me that Sir Stratford Canning had presented the sculptures discovered in Assyria, and had made over all advantages that might be derived from the order given to him by the Sultan, to the British nation; and that the British Museum had received a grant of funds for the continuation of the researches commenced at Nimroud, and elsewhere. The grant was small, and scarcely adequate to the objects in view. There were many difficulties to contend with, and I was doubtful whether, with the means placed at my disposal, I should be able to fulfil the expectations which appeared to have been formed, as to the results of the undertaking. The sum given to M. Botta for the excavations at Khorsabad alone, greatly exceeded the whole grant to the Museum, which was to include private expenses, those of carriage, and many extraordinary outlays inevitable in the East, when works of this nature are to be carried on. I determined, however, to accept the charge of superintending the excavations, to make every exertion, and to economise as far as it was in my power — that the nation might possess as extensive and complete a collection of Assyrian antiquities as, considering the smallness of the means, it was possible to collect. I had neither knowledge nor experience as a draughtsman; and this I felt to be a great drawback, indeed a disqualification, which I could scarcely hope to overcome. Many of the sculptures, and monuments discovered, were in too dilapidated a condition to be removed, and others threatened to fall to pieces as soon as uncovered. It was only by drawings that the record of them could be preserved. There was no inclination to send an artist to assist me, and I made up my mind to do the best I could; to copy as carefully and accurately as possible, that which I saw before me. I had therefore to superintend the excavations; to draw all the bas-reliefs discovered; to copy and compare the innumerable inscriptions; to take casts of them1; and to preside over the moving and packing of the sculptures. As there was no one whom I could trust to overlook the diggers, I was obliged to be continually present, and frequently to remove the earth myself from the face of the slabs — as, through the carelessness and inexperience of the workmen, they were exposed to injury from the blows of the picks. I felt that I was far from qualified to undertake these multifarious occupations. I knew, however, that if persons equal to the task, and sufficiently well acquainted with the various languages of the country to carry on the necessary communications with the authorities, and to hold the requisite intercourse with the inhabitants — Arabs, Kurds, Turks, and Chaldaeans — were sent out expressly from England, the whole sum granted would be expended before the excavations could be commenced. The researches would probably be then less extensive, and their results less complete than they would be if, however unqualified, I at once undertook their superintendence. I determined, therefore, to devote the whole of my time to the undertaking, and to make every sacrifice to ensure its success. It was, in the first place, necessary to organise a band of workmen best fit to carry on the work. The scarcity of corn, resulting from the oppressive measures of Mohammed Pasha, and from the large exportation which had been made to Syria and the sea-coast, had driven the Arab tribes to the neighbourhood of the town, where they sought to gain a livelihood by engaging in labours not very palatable to a Bedouin. I had no difficulty in finding workmen amongst them. There was, at the same time, this advantage in emploing these wandering Arabs — they brought their tents and families with them, and, encamping round the ruins and the village, formed a very efficient guard against their brethren of the Desert, who looked to plunder, rather than to work, to supply their wants. To increase my numbers I chose only one man from each family; and, as his male relations accompanied him, I had the use of their services, as far as regarded the protection of my sculptures. Being well acquainted with the Sheikhs of the Jebour, I chose my workmen chiefly from that tribe. The chiefs promised every protection; and I knew enough of the Arab character not to despair of bringing the men under proper control. The Arabs were selected to remove the earth — they were unable to dig; this part of the labour required stronger and more active men; and I chose for it about fifty Nestorian Chaldaeans, who had sought work for the winter in Mosul, and many of whom, having already been employed, had acquired some experience in excavating. They went to Nimroud with their wives and families. I engaged at the same time one Bainan, a Jacobite or Syrian Christian, who was a skilful marble-cutter, and a very intelligent man. I had made also a valuable addition to my establishment in a standard-bearer of the irregular troops, of whose courage I had seen such convincing proofs during the expedition to the Sinjar, that I induced his commander to place him in my service. His name was Mohammed Agha; but he was generally called, from his rank, the "Bairakdar." He was a native of Scio, and had been carried off at the time of the massacre, when a child, by an irregular, who had brought him up as a Mussulman. In his religious opinions and observances, however, he was as lax, as men of his profession usually arc. He served me faithfully and honestly, and was of great use during the excavations. Awad still continued in my employ; my Cawass, Ibrahim Agha, returned with me to Nimroud; and I hired a carpenter and two or three men of Mosul as superintendents. I was again amongst the ruins by the end of October. The winter season was fast approaching, and it Avas necessary to build a proper house for the shelter of myself and servants. I marked out a plan on the ground, on the outside of the village of Nimroud, and in a few days the habitations were complete. My workmen formed the walls of mud bricks, dried in the sun, covering in the rooms with beams and branches of trees. A thick coat of mud was laid over the whole, to exclude the rain. I built two rooms for myself, divided by an I wan, or open apartment, the whole being surrounded by a wall. In a second courtyard were huts for my Cawass, for Arab guests, and for my servants, and stables for my horses. Ibrahim Agha displayed his ingenuity by making equidistant loop-holes, of a most warlike appearance, in the walls; which I immediately ordered to be filled up, to avoid any suspicion of being the constructor of forts and castles, with the intention of making a permanent Frank settlement in the country. We did not neglect precautions, however, in case of an attack from the Bedouins, of whom Ibrahim Agha was in constant dread. Unfortunately, the only showers of rain that I saw during the remainder of my residence in Assyria, fell before my walls were covered in, and so saturated the bricks that they did not become again dry before the following spring. The consequence was, that the only verdure, on which my eyes were permitted to feast before my return to Europe, was furnished by my own property — the walls in the interior of the rooms being continually clothed with a crop of grass. On the mound itself, and immediately above the great winged lions first discovered, I built a house for my Nestorian workmen and their families, and a hut, to which I could at once remove for safety any small objects discovered among the ruins. I divided my Arabs into three parties, according to the branches of the tribe to which they belonged. About forty tents were pitched on different parts of the mound, at the entrances to the principal trenches. Forty more were placed round my dwelling, and the rest on the bank of the river, where the sculptures were deposited previous to their embarcation on the rafts. The men were all armed. I thus provided for the defence of all ray establishment. Mr. Hormuzd Rassam lived with me; and to him I confided the payment of the wages, and all the accounts. He soon obtained an extraordinary influence amongst the Arabs, and his fame spread through the desert. I divided my workmen into parties. In each set were generally eight or ten Arabs, who carried away the earth in baskets; and two, or four, Nestorian diggers, according to the nature of the soil and rubbish which had to be removed. They were overlooked by a superintendent, whose duty it was to keep them to their work, and to give me notice when the diggers approached any slab, or exposed any small object to view, that I might myself assist in the uncovering or removal. I scattered a few Arabs of a hostile tribe amongst the rest, and by that means I was always made acquainted with what was going on, could easily learn if there were plots brewing, and could detect those who might attempt to appropriate any relics discovered during the excavations. The smallness of the sum placed at my disposal, compelled me to follow the same plan in the excavations that I had hitherto adopted, — viz. to dig trenches along the sides of the chambers, and to expose the whole of the slabs, without removing the earth from the centre. Thus, few of the chambers were fully explored; and many small objects of great interest may have been left undiscovered. As I was directed to bury the building with earth after I had explored it, to avoid unnecessary expense I filled up the chambers with the rubbish taken from those subsequently uncovered, having first examined the walls, copied the inscriptions, and drawn the sculptures. The excavations were recommenced, on a large scale, by the 1st of November. ^ly working parties were distributed over the mound — in chambers, B, G, and I, of the palace or edifice represented in plan 3; in the centre of the mound near the gigantic bulls2; in the S. E. corner, where as yet no traces of building had been discovered; and at walls a and d of plan 2. I also opened trenches in parts of the ruins hitherto unexamined. It will be remembered that in chamber B (plan 3), the slabs from No. 2. to entrance b, had fallen with their faces to the ground. I was, in the first place, anxious to raise these bas-reliefs, and to pack them for removal to Busrah. To accomplish this, I had to remove a large accumulation of earth and rubbish — to empty, indeed, almost the whole chamber, for the fallen slabs extended almost half-way across it. The sculptures from No. 3. to 11. (inclusive) were found to be in admirable preservation, although the slabs were broken by the fall. They were divided, as those already described3, into two compartments, separated by an inscription running across the slab. All these inscriptions were precisely similar. The bas-reliefs, above and below, were of the highest interest. They represented the wars of the king, and the conquest of some strange people. The two upper bas-reliefs, on slabs Nos. 3. and 4., formed one subject — the king followed by warriors, in battle with his enemies under the walls of a hostile castle. He stands, gorgeously attired, in a chariot, drawn, as usual, by three horses richly caparisoned. He is discharging an arrow either against the besieged, who are defending the towers and walls; or against a warrior, who, already wounded, is tumbling from his chariot, one of the horses having fallen to the ground. An attendant protects the person of the king with a shield, whilst a second is holding the reins and urging on the horses. A warrior, fallen from the chariot of the enemy, is almost under the horses' feet. Above the king discharging an arrow, the head of which is in the form of a trident, is the great Deity, represented — as at Persepolis — by a winged figure within a circle. He wears the horned cap resembling that of the human-headed lions and bulls. Behind the king are three chariots; the first, drawn by three horses — one of which is rearing and another falling — is occupied by a warrior already pierced by an arrow, and apparently demanding quarter of the pursuers. In the two other chariots are two warriors, one discharging an arrow, the other guiding the horses, which are at full speed. In each chariot is a standard — on one is an archer, with the horned cap but without wings, standing on a bull; on the other two bulls, back to back. At the bottom of the first bas-relief, are wavy lines, to indicate water or a river, and trees are scattered over both. Groups of men, fighting or slaying the enemy, are introduced in several places; and three headless bodies above the principal figures in the second bas-relief represent the dead in the background.4 On the two next slabs was the return after victory. In front of the procession are several warriors carrying heads, and throwing them at the feet of the conquerors. Two musicians are playing with a plectrum, on stringed instruments, or harps similar to those on slabs Nos. 19. and 20. of the same chamber.5 They are followed by the warriors, who were represented in battle in the previous bas-relief, now unarmed, and holding their standards before them; above them flies an eagle with a human head in his talons. Behind them is the king carrying in one hand his bow, and in the other two arrows; the position in which he is so frequently represented on Assyrian monuments, and probably denoting triumph over his enemies: above the horses is the presiding divinity; also holding his bow in his hand. The second warrior, who bore the shield, is now replaced by an eunuch, raising the parasol, the emblem of royalty, above the monarch's head; the third warrior still holds the reins of the horses, which are led by grooms standing at their heads. Behind the king's chariot is a horseman leading a second horse, gaily caparisoned. After the procession, we have the castle and pavilion of the conquering king. The ground plan of the former is represented by a circle, divided into four equal compartments, and surrounded by towers and battlements. In each compartment there are figures apparently engaged in various culinary occupations, and preparing the feast; one is holding a sheep, which the other is cutting up: another appears to be baking bread. Various bowls and utensils are placed on tables and stools, all remarkable for the elegance of their forms. The pavilion is supported by three posts or columns; on the summit of one is the fir-cone, — the emblem so frequently found in the Assyrian sculptures; on the others are figures of the ibex or mountain goat, their feet brought together as if preparing to jump. They are designed with great spirit, and carefully executed. The material — probably silk or woollen stuff, — with which the upper part of the pavilion is covered, is richly ornamented and edged with a fringe of fir-cones, and another ornament which generally accompanies the fir-cone when used in the embroidery of dresses, and in the decoration of rooms. Beneath the canopy is a groom cleaning one horse; whilst others, picketted by their halters, are feeding at a trough. An eunuch, who appears to stand at the entrance of the tent, is receiving four prisoners, with their hands tied behind, brought in by a warrior in a pointed helmet. Above this group are two singular figures, uniting the human form with the head of a lion. One holds a whip or a thong in the right hand, and grasps his under jaw with the left. The hands of the second are elevated and joined in front. They wear under- tunics descending to the knees; and a skin falls from the head, over the shoulders, down to the ankles. They are accompanied by a man clothed in a short tunic, and raising a stick with both hands. The four following bas-reliefs represent a battle, in which the king, the two warriors with their standards, and an eunuch are represented in chariots; and four warriors, amongst whom is also an eunuch, on horses. The enemy are on foot, some wounded, some dead; others discharging their arrows against the pursuers. Eagles fly above the victors, and one is already feeding on a dead body. The winged divinity in the circle, is again seen above the king. These bas-reliefs are executed with great spirit, particularly that containing the horsemen. On the lower series of bas-reliefs are represented three subjects — the siege of a castle, the king receiving his prisoners, and the king, with his army crossing a river. The first occupies the under compartments of three slabs. The greater part of the castle is in the centre bas-relief It has three towers, and apparently several walls, one behind the other. They are all surmounted by angular battlements. The besiegers have brought a battering ram (attached to a moveable tower, apparently constructed of wicker-work) up to the wall, from which many stones have already been dislodged and are falling. One of the besieged has succeeded in catching the ram by a chain, and is endeavouring to raise or move it from its place; whilst two warriors of the assailing party are holding it down by hooks, to which they are hanging. Another is throwing fire (traces of the red paint being still retained in the sculpture) from above, upon the engine; which the besiegers endeavour to quench, by pouring water upon it from two spouts in the moveable tower. Two figures, in full armour, are undermining the walls with instruments like blunt spears; whilst two others appear to have found a secret passage into the castle. Three of the besieged are falling from the walls; and upon one of the towers are two women, tearing their hair and extending their hands, as if in the act of asking for mercy. The enemy are already mounting to the assault, and scaling ladders have been placed against the walls. The king, discharging an arrow, and defended by a warrior in complete armour, who holds a shield before him, stands on one side of the castle. He is attended by two eunuchs, one holding the umbrella, the other his quiver and mace. Behind them is a warrior, leading away captive three women and a child; and driving three bullocks, a part of the spoil. The women are tearing their hair. On the other side of the castle are two kneeling figures, one discharging an arrow, the other holding a wicker shield for his companion's defence. Behind them is the vizir, also discharging an arrow, and protected by the shield of a second warrior. He is followed by three more warriors, the first kneeling, and two behind in complete armour, erect — one bending the bow, the other raising a shield. They appear to have left their chariot, in which the charioteer is still standing. The heads of the horses are held by a groom; and behind the chariot are two warriors, carrying each a bow and a mace. Upon the lower part of the three next slabs, is the king receiving captives; the subject being treated, With the exception of the prisoner, — who is here omitted, — and of the grouping of the figures, in the same manner as that on Nos. 17. and 18. in this chamber, and already described.6 Behind the chariot of the king, however, are two other chariots each containing a charioteer alone: they are passing under the walls of a castle, in which are women in animated conversation, probably viewing the procession, or discussing the results of the expedition. The three remaining bas-reliefs are highly interesting, and curious. The first represents a boat containing a chariot, in which is the king. In one hand he holds two arrows, in the other a bow. An eunuch, standing in front of the chariot, is talking with the king, and is pointing with his right hand to some object in the distance, perhaps the stronghold of the enemy. Behind the chariot is a second eunuch, holding a bow, and a mace. The boat is towed by two naked men, who are walking on dry land; and four men row the vessel with oars. One oar, with a broad flat extremity, is passed through a rope, hung round a thick wooden pin at the stern, and serves both to guide and impel the boat. It is singular that this is precisely the mode adopted by the inhabitants of Mosul to this day, when they cross the Tigris in barks, perhaps even more rude than those in use, on the same river, three thousand years ago. A charioteer, standing in the vessel, holds by the halters four horses, who are swimming over the stream. A naked figure is supporting himself upon an inflated skin, — a mode of swimming rivers still practised in Mesopotamia. In fact, the three bas-reliefs, with the exception of the king and the chariot, might represent a scene daily witnessed on the banks of the Tigris, — probably the river here represented. The water is shown by undulating lines, covering the face of the slab. On the next slab are two smaller boats; in the first appears to be the couch of the king, and a jar or large vessel; in the other an empty chariot: they are each impelled by two men, seated face to face at their oars. Five other figures, two leading horses by their halters, are swimming on skins. Two fish are represented in the water. On the third slab is the embarcation — men are placing two chariots in a boat, which is about to leave the shores; two warriors, one with, and the other without, support, are already swimming over; and two others are filling and tying up their skins on the bank. Behind them, on dry land, are three figures erect, probably officers superintending the proceedings; one of whom, an eunuch, holds a whip in his right hand, which may have been used — as in the army of Xerxes — to keep the soldiers to their duty, and prevent them flying from the enemy.7 Chamber I had only been partly uncovered; the slabs were still half buried, and the pavement was covered to the height of six feet. A party of Arabs were employed in removing the remaining earth. As we approached the floor, a large quantity of iron was found amongst the rubbish; and I soon recognised in it, the scales of the armour represented on the sculptures. Each scale was separate, and was of iron, from two to three inches in length, rounded at one end, and squared at the other, with a raised or embossed line in the centre. The iron was covered with rust, and in so decomposed a state, that I had much difficulty in cleansing it from the soil. Two or three baskets were filled with these relics. As the earth was removed, other portions of armour were found; some of copper, others of iron, and others of iron inlaid with copper. At length a perfect helmet, resembling in shape, and in the ornaments, the pointed helmet represented in the bas-reliefs, was discovered. When the rubbish was cleared away it was perfect, but immediately fell to pieces. I carefully collected and preserved the fragments, which have been sent to England. The lines which are seen round the lower part of the pointed helmets in the sculptures, are thin strips of copper, inlaid in the iron. Several helmets of other shapes, some with the arched crest, were also uncovered; but they fell to pieces as soon as exposed; and I was only able, with the greatest care, to gather up a few of the fragments which still held together, for the iron was in so complete a state of decomposition that it crumbled away on being touched. Portions of armour in copper, and embossed, were also found, with small holes for nails round the edges. The slabs numbered 8, 9, 10, and 11 on the plan8 had fallen from their places, and were broken into small pieces. I raised them, and discovered under them — but of course broken into a thousand fragments — a number of vases of the finest white alabaster, and several vessels of baked clay. I carefully collected these fragments, but it was impossible to put them together. I found, however, that upon some of them cuneiform characters were engraved, and I soon perceived the name and title of the Khorsabad king, accompanied by the figure of a lion. Upon the pottery were several characters differently formed, resembling those sometimes seen on monuments of Babylonia and Phoenicia, probably a cursive writing in common use; whilst the cuneiform, or more complex letters, were reserved for monumental and sacred inscriptions. The earthen vases appear to have been painted of a light yellow colour, and ornamented with bars, zig-zag lines, and simple designs in black. Whilst I was collecting and examining these curious relics, a workman digging away the earth from a corner of the chamber, between slabs 20 and 21, came upon a perfect vase; but unfortunately struck it with his pick, and broke away the upper part of it. I took the instrument, and, working cautiously myself, was rewarded by the discovery of two small vases, one in alabaster, the other in glass, (both in the most perfect preservation,) of elegant shape, and admirable workmanship. Each bore the name and title of the Khorsabad king, written in two different ways, as in the inscriptions of Khorsabad. A kind of exfoliation had taken place in the glass vase, and it was incrusted with, thin, semi-transparent lamina, which glowed with all the brilliant colours of the opal. This beautiful appearance is a well-known result of age, and is frequently found on glass in Egyptian, Greek, and other early tombs. From the inscription on the vases, it was evident that this chamber had been opened; or that the building was still standing in the time of the king who built the palace at Khorsabad. In front of the bas-reliefs Nos. 13. and 18., in the same chamber, were two large slabs slightly hollowed, similar to those in hall B, already described9; and there were also two recesses, resembling that in chamber H10, nearly opposite one another, in the upper part of the chamber. In the lower compartment of slab No. 16. were two beardless figures, which, from a certain feminine character in the features, and from a bunch of long hair falling down their backs, appear to be women. They wear the same horned cap as the bearded figures, and, like them, have wings. They are facing one another, and between them is the usual sacred tree. They hold in one hand a garland or chaplet; and raise the other towards the symbolical or sacred tree, placed between them. They wear a necklace, to which is appended several circular medallions, having stars cut upon them, probably also symbolical. The shape of this chamber was singular. It had two entrances, one communicating with the rest of the building, the other leading into a small room, from which there was no other outlet. It resembled a long passage, turning abruptly at right angles, and opening into a wider, though still an elongated, apartment. In chamber J, nothing of any importance was discovered. The slabs were unsculptured; upon each of them was the usual inscription, which was also cut upon the slabs forming the pavement. It will be observed by a reference to the plan (3), that there was a recess in one of the corners, resembling a doorway or entrance; but the communication with chamber H, was cut off by a single slab. As it is not probable that the wall of sun-dried bricks was carried up to the roof in this place, there may have been an opening here, to admit light and air. However, it is difficult to account for half the architectural mysteries in this strange building. The entrance formed by the pair of small human-headed lions, discovered in chamber G, led me into a new hall, which I did not then explore to any extent, as the slabs were not sculptured. It was in the centre of the mound, however, that one of the most remarkable discoveries awaited me. I have already mentioned the pair of gigantic winged bulls, first found there.11 They appeared to form an entrance and to be only part of a large building. The inscriptions upon them contained a name, differing from that of the king, who had built the palace in the north-west corner. On digging further I found a brick, on which was a genealogy, the new name occurring first, and as that of the son of the founder of the earlier edifice. This was, to a certain extent, a clue to the comparative date of the newly discovered building. I now sought for the walls, which must have been connected with the bulls. I dug round these sculptures, but found no other traces of building, except a few squared stones, fallen from their original places. As the backs of the bulls were completely covered with inscriptions, in large and well- formed cuneiform characters, I was led to believe that they might originally have stood alone. Still there must have been other slabs near them. I directed a deep trench to be carried, at right angles, behind the northern bull. After digging about ten feet, the workmen found a slab lying flat on the. brick pavement, and having a gigantic winged figure sculptured in relief upon it. It resembled some already described; and carried the fir-cone, and the square basket or utensil, but there was no inscription across it. Beyond was a similar figure, still more gigantic in its proportions, being about fourteen feet in height. The relief was low, and the execution inferior to that of the sculptures discovered in the other palaces. The beard and part of the legs of a winged bull, in yellow limestone, were next found. These remains, imperfect as they were, promised better things. The trench was carried on in the same direction for several days; but nothing more appeared. It had reached above fifty feet in length, and still without any new discovery. I had business in Mosul, and was giving directions to the workmen to guide them during my absence. Standing on the edge of the hitherto unprofitable trench, I doubted whether I should carry it any further; but made up my mind at last, not to abandon it until my return, which would be on the following day, I mounted my horse; but had scarcely left the mound when a corner of black marble was uncovered, lying on the very edge of the trench. This attracted the notice of the superintendent of the party digging, who ordered the place to be further examined. The corner was part of an obelisk, about seven feet high, lying on its side, ten feet below the surface. An Arab was sent after me without delay, to announce the discovery; and on my return I found the obelisk completely exposed to view. I descended eagerly into the trench, and was immediately struck by the singular appearance, and evident antiquity, of the remarkable monument before me. We raised it from its recumbent position, and, with the aid of ropes, speedily dragged it out of the ruins. Although its shape was that of an obelisk, yet it was flat at the top and cut into three gradines. It was sculptured on the four sides; there were in all twenty small bas-reliefs, and above, below, and between them was carved an inscription 210 lines in length. The whole was in the best preservation; scarcely a character of the inscription was wanting; and the figures were as sharp and well defined as if they had been carved but a few days before. The king is twice represented, followed by his attendants; a prisoner is at his feet, and his vizir and eunuchs are introducing men leading various animals, and carrying vases and other objects of tribute on their shoulders, or in their hands. The animals are the elephant, the rhinoceros, the Bactrian or two-humped camel, the wild bull, the lion, a stag, and various kinds of monkeys. Amongst the objects carried by the tribute-bearers, may perhaps be distinguished the tusks of the elephant, shawls, and some bundles of precious wood. From the nature, therefore, of the bas-reliefs, it is natural to conjecture that the monument was erected to commemorate the conquest of India, or of some country far to the east of Assyria, and on the confines of the Indian peninsula. The name of the king, whose deeds it appears to record, is the same as that on the centre bulls; and it is introduced by a genealogical list containing many other royal names.

I lost no time in copying the inscriptions, and drawing the bas-reliefs, upon this precious relic. It was then carefully packed, to be transported at once to Baghdad. A party of trustworthy Arabs were chosen to sleep near it at night; and I took every precaution that the superstitions and prejudices of the natives of the country, and the jealousy of rival antiquaries, could suggest. In the south-east corner, discoveries of scarcely less interest and importance were made, almost at the same tune. The workmen were exploring the walls a and d12; on reaching the end of them, they discovered a pair of winged lions, of which the upper part, including the head, was almost entirely destroyed. They differed in many respects from those forming the entrances of the north-west palace. They had but four legs; they were carved out of a coarse limestone, and not out of alabaster; and behind the body of the lion, and in front behind the horned cap, and above the wings, were sculptured several figures, which were unfortunately greatly injured, and could with difficulty be traced. Behind the lion was a carved monster, uniting the head of an eagle or vulture, width the body and arms of a man, and the tail of a fish or dragon. Beneath were two figures, one of which — a priest carrying a pole tipped by the oft-recurring fir-cone — could alone be distinguished. In front were two human figures, one with the head of a lion raising a stick in one hand, as if in the act of striking. Between the two lions, forming this entrance, were a pair of crumbling sphinxes. They differed from all Assyrian sculptures hitherto discovered; nor could I form any conjecture as to their original use. They were not in relief, but entire. The head was beardless; but whether male or female, I cannot positively determine: the horned cap was square, and highly ornamented at the top, resembling the head-dress of the winged bulls at Khorsabad. The body was that of a lion. A pair of gracefully formed wings appeared to support a kind of platform, or the base of a column; but no trace of a column could be found. These sphinxes may have been altars for sacrifice, or places to receive offerings to the gods, or tribute to the king. There was no inscription upon them, by which they could be connected with any other building.

The whole entrance was buried in charcoal, and the fire which destroyed the building, appears to have raged in this part with extraordinary fury. The sphinxes were almost reduced to lime; one had been nearly destroyed; but the other, although broken into a thousand pieces, was still standing when uncovered. I endeavoured to secure it with rods of iron, and wooden planks; but the alabaster was too much decomposed to resist exposure to the atmosphere. I had scarcely time to make a careful drawing, before the whole fell to pieces: the fragments were too small to admit of their being collected, with a view to future restoration. The sphinxes, when entire, were about five feet in height and in length. Whilst superintending the removal of the charcoal, blocking up the entrance formed by the winged lions just described, I found a small head in alabaster, with the high horned cap, precisely similar to that of the large sphinx. A few minutes afterwards, the body of the crouching lion was dug out, and I had then a complete and very beautiful model of the larger sculptures. It had been injured by the fire, but was still sufficiently well preserved to show accurately the form, and details. In the same place I discovered the bodies of two lions, united and forming of a platform or pedestal, similar to that formed by the one crouching sphinx; but the human heads were wanting, and the rest of the sculpture had been so much injured by fire, that I was unable to preserve it. The plan, and nature of the edifice in the S.W. corner, was still a mystery to me. All the slabs hitherto uncovered had evidently been brought from another building; chiefly from that in the N.W. part of the mound. The discovery of the entrance I have just described, proved this beyond a doubt; as it enabled me to distinguish between the back and the front of the walls. I was now convinced that the sculptures hitherto found, were not meant to be exposed to view; they were, in fact, placed against the wall of sun-dried bricks; and the back of the slab, smoothed preparatory to being re-sculptured, was turned towards the interior of the chambers. I had not yet had sufficient experience in the Assyrian character, to draw any inference from the inscriptions occurring on the bricks, found amongst the ruins in this part of the mound, so as to connect the name of the King upon them, with that of the founder of any known building. There were no inscriptions between the legs and behind the bodies of the lions just described, as in other buildings at Nimroud and Khorsabad. I had not yet found any sculptures unaccompanied by the name and genealogy of the founders of the edifice in which they had been placed. When no inscription was on the face, it was invariably to be found on the back of the slab. I determined, therefore, to dig behind the lions. I was not disappointed in my search; a few lines in the cuneiform character were discovered, and I recognised at once the names of three kings in genealogical series. The name of the first king in the series, or the founder of the edifice, was identical with that of the builder of the N.W. palace; that of his father with the name on the bricks found in the ruins opposite Mosul; that of his grandfather with the name of the builder of Khorsabad. This fortunate discovery served to connect the latest palace at Nimroud, with two of the most important cities or edifices in Assyria; and subsequently with important monuments existing in other parts of Asia. It will be shown hereafter, upon what evidence the proof of the facts I have here stated rests.13 Whilst excavations were thus successfully carried on in the centre, and amongst the ruins of the two palaces first opened, discoveries of a different nature were made in the S.E. corner, which was much higher than any other part of the mound. I dug to a considerable depth, without meeting with any traces of building. Fragments of inscribed bricks, and of pottery, appeared in abundance; and a few earthen vessels, and jars well preserved, were found amongst the rubbish. One morning, the superintendent of the workmen informed me that a slab had been uncovered, bearing an inscription. I hastened to the spot, and saw the stone he had described lying at the bottom of the trench. Upon it was the name of the same king, written as on the centre bulls. The slab having been partly destroyed, the inscription was imperfect. I ordered it to be raised, with the intention of copying it. This was quickly effected with the aid of an iron crow; when, to my surprise, I found that it had been used as the lid of an earthen sarcophagus, which, with its contents, was still entire beneath. The sarcophagus was about five feet in length, and very narrow. The skeleton was well preserved, but fell to pieces almost immediately on exposure to the air: by its side were two jars in baked clay of a red colour, and a small alabaster bottle, all precisely resembling, in shape, similar vessels discovered in Egyptian tombs. There was no other clue to the date, or origin of the sepulchre. The sarcophagus was too small to contain a man of ordinary size when stretched at full-length; and it was evident, from the position of the skeleton, that the body had been doubled up when forced in. A second earthen case was soon found, differing in form from the first. It resembled a dish-cover, and was scarcely four feet long. In it were other vessels of baked clay. Its lid was a slab taken from some building, like the lid of the sarcophagus first discovered. Although the skulls were entire when first exposed to view, they crumbled into dust as soon as touched, and I was unable to preserve either of them. The six weeks following the commencement of excavations upon a large scale, were amongst the most prosperous, and fruitful in events, during my researches in Assyria. Every day produced some new discovery. My Arabs entered with alacrity into the work, and felt almost as much interested in its results as I did myself. They were now well organised, and I had no difficulty in managing them. Even their private disputes, and domestic quarrels were referred to me. They found this a cheaper fashion of settling their differences than litigation; and I have reason to hope that they received an ampler measure of justice than they could have expected at the hands of his reverence, the Cadi. The tents had greatly increased in numbers, as the relatives of those who were engaged in the excavations came to Nimroud, and swelled the encampment; for although they received no pay, they managed to live upon the gains of their friends. They were, moreover, preparing to glean, — in the event of there being any crops in the spring, — and to take possession of little strips of land along the banks of the river, upon which they might cultivate millet during the summer. They already began to prepare water-courses, and machines for irrigation. The mode of raising water, generally adopted in the country traversed by the rivers of Mesopotamia, is very simple. In the first place a high bank, which is never completely deserted by the river, must be chosen. A broad recess, down to the water's edge, is then cut in it. Above, on the edge of this recess, are fixed three or four upright poles, according to the number of oxen to be employed, united at the top by rollers running on a swivel, and supported by a large framework of boughs and grass, extending to some distance behind, and intended as a shelter from the sun during the hot days of summer. Over each roller are passed two ropes, the one being fastened to the mouth, and the other to the opposite end, of a sack, formed out of an entire bullock skin. These ropes are attached to oxen, who throw all their weight upon them by descending an inclined plane, cut into the ground behind the apparatus. A trough formed of wood, and lined with bitumen, or a shallow trench, coated with matting, is constructed at the bottom of the poles, and leads to the canal running into the fields. When the sack is drawn up to the roller, the ox turns round at the bottom of the inclined plane, and the rope attached to the lower part of the bucket being fastened to the back part of the animal, he raises the bottom of the sack, in turning, to the level of the roller, and the contents are poured into the troughs. As the ox ascends, the bucket is lowered; and, when filled, by being immersed into the stream, is again raised and emptied, as I have described. Although this mode of irrigation is very toilsome, and requires the constant labour of several men and animals, it is generally adopted on the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates. In this way all the gardens of Baghdad and Busrah are watered; and by these means the Arabs, who condescend to cultivate, — when, from the failure of the crops, famine is staring them in the face, — raise a little millet to supply their immediate wants. The principal public quarrels, over which my jurisdiction extended, related to property abstracted, by the Arabs, from one another's tents. These I disposed of in a summary manner, as I had provided myself with handcuffs; and Ibrahim Agha, and the Bairakdar were always ready to act with energy and decision, to show how much they were devoted to my service. But the domestic dissensions were of a more serious nature, and their adjustment offered far greater difficulties. They related, of course, always to the women. As soon as the workmen saved a few plasters, their thoughts were turned to the purchase of a new wife, a striped cloak, and a spear. To accomplish this, their ingenuity was taxed to the utmost extent. The old wife naturally enough raised objections, and picked a quarrel with the intended bride, which generally ended in an appeal to physical force. Then the fathers and brothers were dragged into the affair; from them it extended to the various brandies of the tribe, always anxious to fight for their own honour, and for the honour of their women. At other times, a man repented himself of his bargain, and refused to fulfil it; or a father, finding his future son-in-law increasing in wealth, demanded a higher price for his daughter — a breach of faith which would naturally lead to violent measures on the part of the disappointed lover. Then a workman, who had returned hungry from his work, and found his bread unbaked, or the water-skin still lying empty at the entrance of his tent, or the bundle of faggots for his evening fire yet ungathered, would, in a moment of passion, pronounce three times the awful sentence, and divorce his wife; or, avoiding such extremities, would content himself with inflicting summary punishment with a tent-pole. In the first case he probably repented himself of his act an hour or two afterwards, and wished to be remarried; or to prove that, being an ignorant man, he had mispronounced the formula, or omitted some words — both being good grounds to invalidate the divorce, and to obviate the necessity of any fresh ceremonies. But the mullah had to be summoned, witnesses called, and evidence produced. The beating was almost always the most expeditious, and really, to the wife, the most satisfactory way of adjusting the quarrel. I had almost nightly to settle such questions as these. Mr. Hormuzd Rassara, who had obtained an immense influence over the Arabs, and was known amongst all the tribes, was directed to ascertain the merits of the story, and to collect the evidence. When this process had been completed, I summoned the elders, and gave judgment in their presence. The culprit was punished summarily, or in case of a disputed bargain, was made to pay more, or to refund, as the case required. It is singular, considering the number of cases thus brought before me, that only on one occasion did either of the parties refuse to abide by my decision. I was sitting one evening in my tent, when a pretty Arab girl rushed into my presence, and throwing herself at my feet, uttered the most dismal lamentations. An old Arab woman, her mother, entered soon after, and a man endeavoured to force his way in, but was restrained by the brawny arms of the Bairakdar. It was some time before I could learn from either the girl or her mother, who were both equally agitated, the cause of their distress. The father, who was dead, had, during his lifetime, agreed to marry his daughter to the man who had followed them to my tent; and the ])rice, fixed at two sheep, a donkey, and a few measures of wheat, had been partly paid. The Arab, who was a stranger, and did not belong to any of the branches of the Jebour from which I had chosen my workmen, had now come to claim his bride; but the girl had conceived a violent hatred for him, and absolutely refused to marry. The mother, who was poor, did not know how to meet the difficulty; for the donkey had already been received, and had died doing his work. She was therefore inclined to give up her daughter, and was about to resign her into the hands of the husband, when the girl fled from their tent, and took refuge with me. Having satisfied myself that the man was of a bad character, and known as a professed thief in a small way (as discreditable a profession as that of a robber on a large scale is honourable), and the girl declaring that she would throw herself into the river rather than marry him, I ordered the mother to give back a donkey, with two sheep by way of interest for the use of the deceased animal, and furnished her privately with the means of doing so. They were tendered to the complainant; but he refused to accept them, although the tribe approved of the decision. As the girl appeared to fear the consequences of the steps she had taken, I yielded to her solicitations, and allowed her to remain under my roof. In the night the man went to the tent of the mother, and stabbed her to the heart. He then fled into the desert. I succeeded after some time in catching him, and he was handed over to the authorities at Mosul; but, during the confusion which ensued on the death of Tahyar Pasha, he escaped from prison, and I heard no more of him. The Arabs, on account of this tragical business, were prejudiced against the girl, and there was little chance of her being again betrothed. I married her, therefore, to an inhabitant of Mosul. When I first employed the Arabs, the women were sorely ill-treated, and subjected to great hardships. I endeavoured to introduce some reform into their domestic arrangements, and punished severely those who inflicted corporal chastisement on their wives. In a short time the number of domestic quarrels was greatly reduced; and the women, who were at first afraid to complain of their husbands, now boldly appealed to me for protection. They had, however, some misgivings as to the future, which were thus expressed by a deputation sent to return thanks after an entertainment: — "O Bey! we are your sacrifice. May God reward you. Have we not eaten wheat bread, and even meat and butter, since we have been under your shadow? Is there one of us that has not now a coloured handkerchief for her head, bracelets, and ankle- rings, and a striped cloak? But what shall we do when you leave us, which God forbid you ever should do? Our husbands will then have their turn, and there will be nobody to help us." These poor creatures, like all Arab women, were exposed to constant hardships. They were obliged to look after the children, to make the bread, to fetch water, and to cut wood, which they brought home from afar on their heads. Moreover they were entrusted with all the domestic duties, wove their wool and goat's hair into clothes, carpets, and tent-canvass; and were left to strike and raise the tents, and to load and unload the beasts of burden when they changed their encamping ground. If their husbands possessed sheep or cows, they had to drive them to the pastures, and to milk them at night. When moving, they carried their children at their backs during the march, and were even troubled with this burden when employed in their domestic occupations, if the children were too young to be left alone. The men sat indolently by, smoking their pipes, or listening to a trifling story from some stray Arab of the desert, who was always there to collect a group around him. At first the women, whose husbands encamped on the mound, brought water from the river; but I released them from this labour by employing horses and donkeys in the work. The weight of a large sheep or goat's skin filled with water, is not inconsiderable. This is hung on the back by cords strapped over the shoulders, and upon it, in addition, was frequently seated the child, who could not be left in the tent, or was unable to follow its mother on foot. The bundles of fire-wood, brought from a considerable distance, were enormous, completely concealing the head and shoulders of those who tottered beneath them. And yet the women worked cheerfully, and it was seldom that their husbands had to complain of their idleness. Some were more active than others. There was a young girl named Hadla, who particularly distinguished herself, and was consequently sought in marriage by all the men. Her features were handsome, and her form erect, and exceedingly graceful. She carried the largest burdens, was never unemployed, and was accustomed, when she had finished the work imposed upon her by her mother, to assist her neighbours in completing theirs. The dinners or breakfasts (for the meal comprised both) of the Arab workmen, were brought to them at the mound, about eleven o'clock, by the younger children. Few had more than a loaf of millet bread, or millet made into a kind of paste, to satisfy their hunger; — wheat bread was a luxury. Sometimes their wives had found time to gather a few herbs, which were boiled in water with a little salt, and sent in wooden bowls; and in spring, sour milk and curds occasionally accompanied their bread. The little children, who carried their father's or brother's portion, came merrily along, and sat smiling on the edge of the trenches, or stood gazing in wonder at the sculptures, until they were sent back with the empty platters and bowls. The working parties eat together in the trenches in which they had been employed. A little water, drank out of a large jar, was their only beverage. Yet they were happy and joyous. The joke went round; or, during the short time they had to rest, one told a story, which, if not concluded at a sitting, was resumed on the following day. Sometimes a pedler from Mosul, driving before him his donkey, laden with raisins or dried dates, would appear on the mound. Buying up his store, I would distribute it amongst the men. This largesse created an immense deal of satisfaction and enthusiasm, which any one, not acquainted with the character of the Arab, might have thought almost more than equivalent to the consideration. The Arabs are naturally hospitable and generous. If one of the workmen was wealthy enough to buy a handful of raisins, or a piece of camel's or sheep's flesh, or if he had a cow, which occasionally yielded him butter or sour milk, he would immediately call his friends together to partake of his feast. I was frequently invited to such entertainments; the whole dinner, perhaps, consisting of half a dozen dates or raisins spread out wide, to make the best show, upon a corn-sack; a pat of butter upon a corner of a flat loaf; and a few cakes of dough baked in the ashes. And yet the repast was ushered in with every solemnity; — the host turned his dirty kefliah, or head-kerchief, and his cloak, in order to look clean and smart; and appeared both proud of the honour conferred upon him, and of his means to meet it in a proper fashion. I frequently feasted the workmen, and sometimes their wives and daughters were invited to separate entertainments, as they would not eat in public with the men. Generally of an evening, after the labours of the day were finished, some Kurdish musicians would stroll to the village with their instruments, and a dance would be commenced, which lasted through the greater part of the night. Sheikh Abdur-rahman, or some Sheikh of a neighbouring tribe, occasionally joined us; or an Arab from the Khabour, or from the most distant tribes of the desert, would pass through Nimroud, and entertain a large circle of curious and excited listeners with stories of recent fights, plundering expeditions, or the murder of a chief. 1 endeavoured, as far as it was in my power, to create a good feeling amongst all, and to obtain their willing co-operation in my work. I believe that I was to some extent successful. The Tiyari, or Nestorian Chaldaean Christians, resided chiefly on the mound, where I had built a large hut for them. A few only returned at night to the village. Many of them had brought their wives from the mountains. The women made bread, and cooked for all. Two of the men walked over to the village of Tel Yakoub, or to Mosul, on Saturday evening, to fetch flour for the whole party, and returned before the work of the day began on Monday morning; for they would not journey on the Sabbath. They kept their holidays, and festivals, with as much rigour as they kept the Sunday. On these days they assembled on the mound or in the trenches; and one of the priests or deacons (for there were several amongst the workmen) repeated prayers, or led a hymn or chant. I often watched these poor creatures, as they reverentially knelt — their heads uncovered — under the great bulls, celebrating the praises of Him whose temples the worshippers of those frowning idols had destroyed, — whose power they had mocked. It was the triumph of truth over Paganism. Never had that triumph been more forcibly illustrated than by those, who now bowed down in the crumbling halls of the Assyrian kings. I experienced some difficulty in settling disputes between the Arabs and the Tiyari, which frequently threatened to finish in bloodshed. The Mussuhnans were always ready, on the slightest provocation, to bestow upon the Chaldaeans the abuse usually reserved in the East for Christians. But the mountaineers took these things differently from the humble Rayahs of the plain, and retorted with epithets very harsh to a Mohammedan's ear. This, of course, led to the drawing of sabres and priming of matchlocks; and it was not until I had inflicted a few summary punishments, that some check was placed upon these disorders. The women retained their mountain habits, and were always washing themselves on the mound, with that primitive simplicity which characterises their ablutions in the Tiyari districts. This was a cause of shame to other Christians in my employ; but the Chaldaeans themselves were quite insensible to the impropriety, and I let them have their way. On Sunday, sheep were slain for the Tiyari workmen, and they feasted during the afternoon. When at night there were music and dances, they would sometimes join the Arabs; but generally performed a quiet dance with their own women, with more decorum, and less vehemence, than their more excitable companions. As for myself I rose at day break, and after a hasty breakfast rode to the mound. Until night I was engaged in drawing the sculptures, copying and moulding the inscriptions, and superintending the excavations, and the removal and packing of the bas-reliefs. On my return to the village, I was occupied till past midnight in comparing the inscriptions with the paper impressions, in finishing drawings, and in preparing for the work of the following day. Such was our manner of life during the excavations at Nimroud; and I owe an apology to the reader for entering into such details. They may, however, be interesting, as illustrative of the character of the genuine Arab, with whom the traveller is seldom brought so much into contact as I have been. Early in December I had collected a sufficient number of bas-reliefs to load another raft, and I consequently rode into Mosul to make preparations for sending a second cargo to Baghdad. I had soon procured all that was necessary for the purpose; and loading a small raft with spars and skins for the construction of a larger, and with mats and felts for packing the sculptures, I returned to Nimroud. The raft-men having left Mosul late in the day, and not reaching the Awai until after nightfall, were afraid to cross the dam in the dark; they therefore tied the raft to the shore, and went to sleep. They were attacked during the night, and plundered. I appealed to the authorities, but in vain. The Arabs of the desert, they said, were beyond their reach. If this robbery passed unnoticed, the remainder of my property, and even my person, might run some risk. Besides, I did not relish the reflection, that the mats and felts destined for my sculptures, were now furnishing the tents of some Arab Sheikh. Three or four days elapsed before I ascertained who were the robbers. They belonged to a small tribe encamping at some distance from Nimroud — notorious in the country for their thieving propensities, and were the dread of my Jebour, whose cattle were continually disappearing in a very mysterious fashion. Having ascertained the position of their tents, I started off one morning at dawn, accompanied by Ibrahim Agha, the Bairakdar, and another irregular horseman, who was in my service. We reached the encampment after a long ride, and found the number of the Arabs to be greater than I expected. The arrival of strangers drew together a crowd, which gathered round the tent of the Sheikh, where I seated myself. A slight bustle was apparent in the women's department. I soon perceived that attempts were being made to hide various ropes and felts, the ends of which, protruding from under the canvass, I had little difficulty in recognising. "Peace be with you! " said I, addressing the Sheikh, who showed by his countenance that he was not altogether ignorant of the object of my visit. "Your health and spirits are, please God, good. we have long been friends, although it has never yet been my good fortune to see you. I know the laws of friendship; that which is my property is your property, and the contrary. But there are a few things, such as mats, felts, and ropes, which come from afar, and are very necessary to me, whilst they can be of little use to you; otherwise God forbid that I should ask for them. You will greatly oblige me by giving these things to me." " As I am your sacrifice, Bey," answered he, "no such things as mats, felts, or ropes were ever in my tents (I observed a new rope supporting the principal pole). Search, and if such things be found we give them to you willingly." "Wallah, the Sheikh has spoken the truth," exclaimed all the bystanders. " That is exactly what I want to ascertain; and, as this is a matter of doubt, the Pasha must decide between us," replied I, making a sign to the Bairakdar, who had been duly instructed how to act. In a moment he had handcuffed the Sheikh; and, jumping on his horse, dragged the Arab, at an uncomfortable pace, out of the encampment. " Now, my sons," said I, mounting leisurely, " I have found a part of that which I wanted; you must search for the rest." They looked at one another in amazement. One man, more bold than the rest, was about to seize the bridle of my horse; but the weight of Ibrahim Agha's courbatch across his back, drew his attention to another object. Although the Arabs were well armed, they were too much surprised to make any attempt at resistance; or perhaps they feared too much for their Sheikh, still jolting away at an uneasy pace in the iron grasp of the Bairakdar, who had put his horse to a brisk trot, and held his pistol cocked in one hand. The women, swarming out of the tents, now took part in the matter. Gathering round my horse, they kissed the tails of my coat and my shoes, making the most dolorous supplications. I was not to be moved, however; and extricating myself with difficulty from the crowd, I rejoined the Bairakdar, who was hurrying on his prisoner with evident good will. The Sheikh had already made himself well-known to the authorities by his dealings with the villages, and there was scarcely a man in the country who could not bring forward a specious claim against him — either for a donkey, a horse, a sheep, or a copper kettle. He was consequently most averse to an interview with the Pasha, and looked with evident horror on the prospect of a journey to Mosul. I added considerably to his alarm, by dropping a few friendly hints on the advantage of the dreary subterraneous lock-up house under the governor's palace, and of the pillory and sticks. By the time he reached Nimroud, he was fully alive to his fate, and deemed it prudent to make a full confession. He sent an Arab to his tents; and next morning an ass appeared in the courtyard bearing the missing property, with the addition of a lamb, and a kid by way of a conciliatory offering. I dismissed the Sheikh with a lecture, and had afterwards no reason to complain of him or of his tribe, — nor indeed of any tribes in the neighbourhood; for the story got abroad, and was invested with several horrible facts in addition, which could only be traced to the imagination of the Arabs, but which served to produce the effect I desired — a proper respect for my property. During the winter Mr. Longworth, and two other English travellers, visited me at Nimroud. As they were the only Europeans (except Mr. Ross), who saw the palace when uncovered14, it may be interesting to the reader to learn the impression which the ruins were calculated to make upon those who beheld them for the first time, and to whom the scene was consequently new. Mr. Longworth, in a letter15, thus graphically describes his visit: — " I took the opportunity, whilst at Mosul, of visiting the excavations of Nimroud. But before I attempt to give a short account of them, I may as well say a few words as to the general impression which these wonderful remains made upon me, on my first visit to them. I should begin by stating, that they are all underground. To get at them, Mr. Layard has excavated the earth to the depth of twelve to fifteen feet, where he has come to a building composed of slabs of marble. In this place, which forms the northwestern angle of the mound, he has fallen upon the interior of a large palace, consisting of a labyrinth of halls, chambers, and galleries, the walls of which are covered with bas-reliefs and inscriptions in the cuneiform character, all in excellent preservation. The upper part of the walls, which was of brick, painted with flowers, &c., in the brightest colours, and the roofs, which were of wood, have fallen; but fragments of them are strewed about in every direction. The time of day when I first descended into these chambers happened to be towards evening; the shades of which, no doubt, added to the awe and mystery of the surrounding objects. It was of course with no little excitement that I suddenly found myself in the magnificent abode of the old Assyrian kings; where, moreover, it needed not the slightest effort of imagination to conjure up visions of their long departed power and greatness. The walls themselves were crowded with phantoms of the past; in the words of Byron, 'Three thousand years their cloudy wings expand;' unfolding to view a vivid representation of those who conquered and possessed so large a portion of the earth we now inhabit. There they were in the Oriental pomp of richly embroidered robes, and quaintly-artificial coiffure. There also were portrayed their deeds in peace and war, their audiences, battles, sieges, lion-hunts, &c. My mind was overpowered by the contemplation of so many strange objects; and some of them, the portly forms of kings and vizirs, were so life-like, and carved in such fine relief, that they might almost be imagined to be stepping from the walls to question the rash intruder on their privacy. Then, mingled with them were other monstrous shapes — the old Assyrian deities, with human bodies, long drooping wings, and the heads and beaks of eagles; or, still faithfully guarding the portals of the deserted halls, the colossal forms of winged lions and bulls, with gigantic human faces. All these figures, the idols of a religion long since dead and buried like themselves, seemed actually in the twilight to be raising their desecrated heads from the sleep of centuries: certainly the feeling of awe which they inspired me with, nmst have been something akin to that experienced by their heathen votaries of old." I was riding home from the ruins one evening with Mr. Longworth. The Arabs returning from their day's work, were following a flock of sheep belonging to the people of the village, shouting their war-cry, flourishing their swords, and indulging in the most extravagant gesticulations. My friend, less acquainted with the excitable temperament of the children of the desert than myself, was somewhat amazed at these violent proceedings, and desired to learn their cause. I asked one of the most active of the party. "Bey," they exclaimed almost all together, " God be praised, we have eaten butter and wheaten bread under your shadow, and are content — but an Arab is an Arab. It is not for a man to carry about dirt in baskets, and to use a spade all his life; he should be with his sword and his mare in the desert. We are sad as we think of the days when we plundered the Anayza, and we must have excitement, or our hearts would break. Let us then believe that these are the sheep Ave have taken from the enemy, and that we are driving them to our tents! " And off they ran, raising their wild cry and flourishing their swords, to the no small alarm of the shepherd, who saw his sheep scampering in all directions, and did not seem inclined to enter into the joke. By the middle of December, a second cargo of sculptures was ready to be sent to Baghdad.16 I was again obliged to have recourse to the buffalo-carts of the Pasha; and as none of the bas-reliefs and objects to be moved were of great weight, these rotten and unwieldy vehicles could be patched up for the occasion. On Christmas day I had the satisfaction of seeing a raft, bearing twenty-three cases, in one of which was the obelisk, floating down the river. I watched them until they were out of sight, and then gallopped into Mosul to celebrate the festivities of the season, with the few Europeans whom duty or business had collected in this remote corner of the globe.

|

|

|

|

|

1) Casts of the inscriptions and of some of the sculptures were taken with brown paper, simply damped and impressed on the slab with a hard brush. 2) At i and j, plan 1. 3) Ante, page 129. 4) These bas-reliefs are already deposited in the British Museum. 5) One of them is now in the British Museum. 6) P. 129. 7) Herod, book vii. ch. 56. in which Xerxes is described as seeing his troops driven by blows over the bridge across the Hellespont; and we learn also from the same author, that it was the custom for the officers to carry whips to urge their soldiers on to the combat: same book, ch. 223. 8) Chamber I, plan 3. 9) P. 134, &c. 10) P. 145. 11) P. 47. 12) Plan 2. 13) See Vol. II. Part II. Chap. I. 14) Mr. Seymour also visited me at Nimroud, but before the excavations were In an advanced stage. 15) Morning Post, March 3d, 1847. 16) Including the obelisk, nearly all the bas-reliefs forming the south wall of chamber B, plan 3, the tablets from chamber I (same plan), with the two female divinities and the kneeling winged figures, and a human head belonging to one of the gigantic bulls, forming an entrance to the palace in the south-west corner (No. 1. entrance c, plan 2). |

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD