Nineveh and Its Remains

Volume 1

By Austen Henry Layard, ESQ. D.C.L.

Part 1 - Chapter 2

My first step on reaching Mosul was to present my letters to the governor of the province. Mohammed Pasha, being a native of Candia, was usually known as Keritli Oglu (the son of the Cretan), to distinguish him from his celebrated predecessor of the same name, who was called, during his lifetime, "Injeh Bairakdar," or the Little Standard-bearer, from the rank he had once held in the irregular cavalry. The appearance of his Excellency was not prepossessing, but it matched his temper and conduct. Nature had placed hypocrisy beyond his reach. He had one eye and one ear; he was short and fat, deeply marked by the small-pox, uncouth in gestures and harsh in voice. His fame had reached the seat of his government before him. On the road he had revived many good old customs and impositions, which the reforming spirit of the age had suffered to full into decay. He particularly insisted on dish-parassi;1 or a compensation in money, levied upon all villages in which a man of such rank is entertained, for the wear and tear of his teeth in masticating; the food he condescends to receive from the inhabitants. On entering Mosul, he had induced several of the principal Aghas who had fled from the town on his approach, to return to their homes; and having made a formal display of oaths and protestations, cut their throats to show how much his word could be depended upon. At the time of my arrival, the population was in a state of terror and despair. Even the appearance of a casual traveller led to hopes, and reports were whispered about the town of the deposition of the tyrant. Of this the Pasha was aware, and hit upon a plan to test the feelings of the people towards him. He was suddenly taken ill one afternoon, and was carried to his harem almost lifeless. On the following morning the palace was closed, and the attendants answered inquiries by mysterious motions, which could only be interpreted in one fashion. The doubts of the Mosuleeans gradually gave way to general rejoicings; but at mid-day his Excellency, who had posted his spies all over the town, appeared in perfect health in the market-place. A general trembling seized the inhabitants. His vengeance fell principally upon those who possessed property, and had hitherto escaped his rapacity. They were seized and stripped, on the plea that they had spread reports detrimental to his authority. The villages, and the Arab tribes, had not suffered less than the townspeople. The Pasha was accustomed to give instructions to those who were sent to collect money, in three words — "Go, destroy, eat;"2 and his agents were not generally backward in entering into the spirit of them. The tribes, who had been attacked and plundered, were retaliating upon caravans and travellers, or laying waste the cultivated parts of the Pashalic. The villages were deserted, and the roads were little frequented and very insecure. Such was the Pasha to whom I was introduced two days after my arrival by the British Vice-Consul, Mr. Rassam. He read the letters which I presented to him, and received me with that civility which a traveller generally expects from a Turkish functionary of high rank. His anxiety to know the object of my journey was evident, but his curiosity was not gratified for the moment. There were many reasons which rendered it necessary that my plans should be concealed, until I was ready to put them into execution. Although I had always experienced from M. Botta the most friendly assistance, there were others who did not share his sentiments; from the authorities and the people of the town I could only expect the most decided opposition. On the 8th of November, having secretly procured a few tools, and engaged a mason at the moment of my departure, and carrying with me a variety of guns, spears, and other formidable weapons, I declared that I was going to hunt wild boars in a neighbouring village, and floated down the Tigris on a small raft constructed for my journey. I was accompanied by Mr. Ross, a British merchant of Mosul3, my Cawass, and a servant. At this time of the year more than five hours are required to descend the Tigris, from Mosul to Nimroud. It was sunset before we reached the Awai, or dam across the river. We landed and walked to the village of Naifa. No light appeared as we approached, nor were we even saluted by the dogs, which usually abound in an Arab village. We had entered a heap of ruins. I was about to return to the raft, upon which we had made up our minds to pass the night, when the glare of a fire lighted up the entrance to a miserable hovel. Through a crevice in the wall, I saw an Arab family crouching round a heap of half-extinguished embers. The dress of the man, the ample cloak and white turban, showed that he belonged to one of the Arab tribes, which cultivate a little land on the borders of the desert, and are distinguished, by their more settled habits, from the Bedouins. Near him were three women, lean and haggard, their heads almost concealed in black handkerchiefs, and the rest of their persons enveloped in the striped aba. Some children, nearly naked, and one or two mangy greyhounds completed the group. As we entered all the party rose, and showed some alarm at this sudden appearance of strangers. The man, however, seeing that we were Europeans, bid us welcome, and spreading some corn-sacks on the ground, invited us to be seated. The women and children retreated into a corner of the hut. Our host, whose name was Awad or Abd-Allah, was a sheikh of the Jehesh. His tribe had been plundered by the Pasha, and was now scattered in different parts of the country; he had taken refuge in this ruined village. He told us that owing to the extortions and perfidy of Keritli Oglu, the villages in the neighbourhood had been deserted, and that the Arab tribe of Abou Salman had moved from the plain of Nimroud, which they usually inhabited, to the south of the Zab, and had joined with the Tai in their marauding excursions into the country on this side of the river. The neighbourhood, he said, was consequently insecure, and the roads to Mosul almost closed. Awad had learnt a little Turkish, and was intelligent and active. Seeing, at once, that he would be useful, I acquainted him with the object of my journey; offering him the prospect of regular employment in the event of the experiment proving successful, and assigning him regular wages as superintendent of the workmen, He had long been acquainted with the ruins, and entertained me with traditions connected with them. "The palace," said he," was built by Athur, the kiayah, or lieutenant of Nimrod. Here the holy Abraham, peace be with him! cast down and brake in pieces the idols which were worshipped by the unbelievers. The impious Nimrod, enraged at the destruction of his gods, sought to slay Abraham, and waged war against him. But the prophet prayed to God, and said, ' Deliver me, God, from this man, who worships stones, and boasts himself to be the lord of all beings,' and God said to him,' How shall I punish him? 'And the prophet answered, ' To Thee armies are as nothing, and the strength and power of men likewise. Before the smallest of thy creatures will they perish.' And God was pleased at the faith of the prophet, and he sent a gnat, which vexed Nimrod night and day, so that he built himself a room of glass in yonder palace, that he might dwell therein, and shut out the insect. But the gnat entered also, and passed by his ear into his brain, upon which it fed, and increased in size day by day, so that the servants of Nimrod beat his head with a hammer continually, that he might have some ease from his pain; but he died after suffering these torments for four hundred years."4 Such are the tales to this day repeated by the Arabs who wander round the remains of a great city; which, by their traditions, they unwittingly help to identify. Awad volunteered to walk, in the middle of the night, to Selamiyah, a village three miles distant, and to some Arab tents in the neighbourhood, to procure men to assist in the excavations. I had slept little during the night. The hovel in which we had taken shelter, and its inmates, did not invite slumber; but such scenes and companions were not new to me: they could have been forgotten, had my brain been less excited. Hopes, long cherished, were now to be realised, or were to end in disappointment. Visions of palaces underground, of gigantic monsters, of sculptured figures, and endless inscriptions, floated before me. After forming plan after plan for removing the earth, and extricating these treasures, I fancied myself wandering in a maze of chambers from which I could find no outlet. Then again, all was reburied, and I was standing on the grass-covered mound. Exhausted, I was at length sinking into sleep, when hearing the voice of Awad, I rose from my carpet, and joined him outside the hovel. The day already dawned; he had returned with six Arabs, who agreed for a small sum to work under my direction. The lofty cone and broad mound of Nimroud broke like a distant mountain on the morning sky. But how changed was the scene since my former visit! The ruins were no longer clothed with verdure and many-coloured flowers; no signs of habitation, not even the black tent of the Arab, was seen upon the plain. The eye wandered over a parched and barren waste, across which occasionally swept the whirlwind dragging with it a cloud of sand. About a mile from us was the small village of Nimroud, like Naifa, a heap of ruins. Twenty minutes' walk brought us to the principal mound. The absence of all vegetation enabled me to examine the remains with which it was covered. Broken pottery and fragments of bricks, both inscribed with the cuneiform character, were strewed on all sides. The Arabs watched my motions as I wandered to and fro, and observed with surprise the objects I had collected. They joined, however, in the search, and brought me handfuls of rubbish, amongst which I found with joy the fragment of a bas-relief. The material on which it was carved had been exposed to fire, and resembled, in every respect, the burnt gypsum of Khorsabad. Convinced from this discovery that sculptured remains must still exist in some part of the mound, I sought for a place where excavations might be commenced with a prospect of success. Awad led me to a piece of alabaster which appeared above the soil. We could not remove it, and on digging downward, it proved to be the upper part of a large slab. I ordered all the men to work around it, and they shortly uncovered a second slab to which it had been united. Continuing in the same line, we came upon a third; and, in the course of the morning, laid bare ten more, the whole forming a square, with one stone missing at the N.W. corner. It was evident that the top of a chamber had been discovered, and that the gap was its entrance.5 I now dug down the face of the stones, and an inscription in the cuneiform character was soon exposed to view. Similar inscriptions occupied the centre of all the slabs, which were in the best preservation; but plain, with the exception of the writing. Leaving half the workmen to uncover as much of the chamber as possible, I led the rest to the S. W. corner of the mound, where I had observed many fragments of calcined alabaster. I dug at once into the side of the mound, which was here very steep, and thus avoided the necessity of removing much earth. We came almost immediately to a wall6, bearing inscriptions in the same character as those already described; but the slabs had evidently been exposed to intense heat, were cracked in every part, and, reduced to lime, threatened to fall to pieces as soon as uncovered. Night interrupted our labours. I returned to the village well satisfied with their result. It was now evident that buildings of considerable extent existed in the mound; and that although some had been destroyed by fire, others had escaped the conflagration. As there were inscriptions, and as the fragment of a bas-relief had been found, it was natural to conclude that sculptures were still buried under the soil. I determined to follow the search at the N. W. corner, and to empty the chamber partly uncovered during the day. On returning to the village, I removed from the crowded hovel in which we had passed the night. With the assistance of Awad, who was no less pleased than myself with our success, we patched up with mud the least ruined house in the village, and restored its falling roof. We contrived at least to exclude, in some measure, the cold night winds; and to obtain a little privacy for my companion and myself. Next morning my workmen were increased by five Turcomans from Selamiyah, who had been attracted by the prospect of regular wages. I employed half of them in emptying the chamber partly uncovered on the previous day, and the rest in following the wall at the S. W. corner of the mound. Before evening, the work of the first was completed, and I found myself in a room built of slabs about eight feet high, and varying from six to four feet in breadth, placed upright and closely fitted too-ether. One of the slabs had fallen backwards from its place; and was supported, in a slanting position, by the soil behind. Upon it was rudely inscribed, in Arabic characters, the name of Ahmed Pasha, one of the former hereditary governors of Mosul. A native of Selamiyah remembered that some Christians were employed to dig into the mound about thirty years before, in search of stone for the repair of the tomb of Sultan Abd- Allah, a Mussulman Saint, buried on the left bank of the Tigris, a few miles below its junction with the Zab. They uncovered this slab; but being unable to move it, they cut upon it the name of their employer, the Pasha. My informant further stated that, in another part of the mound, he had forgotten the precise spot, they had found sculptured figures, which they broke in pieces, the fragments being used in the reparation of the tomb. The bottom of the chamber was paved with smaller slabs than those employed in the construction of the walls. They were covered with inscriptions on both sides, and on removing one of them, I found that it had been placed upon a layer of bitumen which must have been used in a liquid state, for it had retained, with remarkable distinctness and accuracy, an impression of the characters carved upon the stone. The inscriptions on the face of the upright slabs were about twenty lines in length, and all were precisely similar. In one corner, as it has been observed, a slab was wanting, and although nothing could be traced, it was evident from the continuation of the pavement beyond the walls of the chamber, that this was the entrance. As the soil had been worn away by the rains to within a few inches of the tops of the upright slabs, I could form no conjecture as to the original height of the room, or as to how the walls were carried above the casino; of alabaster. In the rubbish near the bottom of the chamber, I found several ivory ornaments, upon which were traces of gilding; amongst them was the figure of a man in long robes, carrying in one hand the Egyptian crux ansata, part of a crouching sphinx, and flowers designed with great taste and elegance. Awad, who had his own suspicions of the object of my search, which he could scarcely persuade himself was limited to mere stones, carefully collected all the scattered fragments of o-old leaf he could find in the rubbish; and, calling me aside in a mysterious and confidential fashion, produced them wrapped up in a piece of dingy paper. "Bey," said he, "Wallah! your books are right, and the Franks know that which is hid from the true believer. Here is the gold, sure enough, and, please God, we shall find it all in a few days. Only don't say any thing about it to those Arabs, for they are asses and cannot hold their tongues. The matter will come to the ears of the Pasha." The Sheikh was much surprised, and equally disappointed, when I generously presented him with the treasures he had collected, and all such as he might hereafter discover. He left me, muttering "Yia Rubbi!" and other pious ejaculations, and lost in conjectures as to the meaning of these strange proceedings. On reaching the foot of the slabs in the S. W. corner, we found a great accumulation of charcoal, which was further evidence of the cause of the destruction of one of the buildings discovered. I dug also in several directions in this part of the mound, and in many places came upon walls branching out at different angles. On the third day, I opened a trench in the high conical mound, and found nothing but fragments of inscribed bricks. I also dug at the back of the north end of the chamber first explored, in the expectation of discovering other walls beyond, but unsuccessfully. As my chief aim was to prove the existence, as soon as possible, of sculptures, all my workmen were moved to the S. W. coiner, where the many ramifications of the building already identified, promised speedier success. I continued the excavations in this part of the mound until the 13th, still uncovering inscriptions, but finding no sculptures. Some days having elapsed since my departure from Mosul, and the experiment having been now sufficiently tried, it was time to return to the town and acquaint the Pasha, who had, no doubt, already heard of my proceedings, with the object of my researches. I started, therefore, early in the morning of the 14th, and galloped to Mosul in about three hours. I found the town in great commotion. In the first place, his Excellency had, on the day before, entrapped his subjects by the reports of his death, in the manner already described, and was now actively engaged in seeking pecuniary compensation for the insult he had received in the rejoicings of the population. In the second, the British Vice-Consul having purchased an old building in which to store his stock in trade, the Cadi, a fanatic and a man of the most infamous character, on the pretence that the Franks had formed a design of buying up the whole of Turkey, was endeavouring to raise a riot, which was to end in the demolition of the Consulate and other acts of violence. I called on the Pasha, and, in the first place, congratulated him on his speedy recovery; a compliment which he received with a grim smile of satisfaction. He then introduced the subject of the Cadi, and the disturbance he had created. " Does that ill-conditioned fellow," exclaimed he, " think that he has Sheriff Pasha (his immediate predecessor) to deal with, that he must be planning a riot in the town? When I was at Siwas the Ulema tried to excite the people because I encroached upon a burying-ground. But I made them eat dirt! Wallah! I took every gravestone and built up the castle walls with them." He pretended at first to be ignorant of the excavations at Nimroud; but subsequently thinking that he would convict me of prevarication in my answers to his questions as to the amount of treasure discovered, pulled out of his writing-tray a scrap of paper, as dingy as that produced by Awad, in which was also preserved an almost invisible particle of gold leaf. This, he said, had been brought to him by the commander of the irregular troops stationed at Selamiyah, who had been watching my proceedings. I suggested that he should name an agent to be present as long as I worked at Nimroud, to take charge of all the precious metals that might be discovered. He promised to write on the subject to the chief of the irregulars; but offered no objection to the continuation of my researches. Reports of the wealth extracted from the ruins had already reached Mosul, and had excited the cupidity and jealousy of the Cadi and principal inhabitants of the place. Others, who well knew my object, and might have spared me any additional interruption without a sacrifice of their national character, were not backward in throwing obstacles in my way, and in fanning the prejudices of the authorities and natives of the town. It was evident that I should have to contend against a formidable opposition; but as the Pasha had not, as yet, openly objected to my proceedings, I hired several Nestorian Chaldeans, who had left their mountains for the winter to seek employment in Mosul, and sent them to Nimroud. At the same time I engaged agents to explore several mounds in the neighbourhood of the town, hoping to ascertain the existence of sculptured buildings in some part of the country, before steps were taken to interrupt me. Whilst at Mosul, Mormons, an Arab of the tribe of Haddedeen, informed me that figures had been accidentally uncovered in a mound near the village of Tel Kef. As he offered to take me to the place, we rode out together; but he only pointed out the site of an old quarry, with a few rudely-hewn stones. Such disappointments were daily occurring; and I wearied myself in scouring the country to see remains which had been most minutely described to me as groups of sculptures, and slabs covered with writing, and which generally proved to be the ruin of some modern building, or an early tombstone inscribed with Arabic characters. The mounds, which I directed to be opened, were those of Baasheikha (of considerable size), Ba-Zani, Karamles, Karakush, Yara, and Jeraiyah. Connected with the latter ruin many strange tales were current in the country. It was said that on it formerly stood a temple of black stone, held in great reverence by the Yezidis, or worshippers of the devil. In this building were all manner of sculptured figures, and the walls were covered with inscriptions in an unknown language. When the Bey of Rowandiz fell upon the Yezidis, and massacred all those who were unable to escape, he destroyed this house of idols; but the materials, of which the walls were built, were only thrown down, and were supposed to be now covered by a small accumulation of rubbish. The lower part of an Assyrian figure, carved in relief on basalt, dug up, it was said, in the mound, was actually brought to me; but I had afterwards reason to suspect that it was discovered at Khorsabad. Excavations were carried on for some time at Jeraiyah, but no remains of the Yezidi temple were brought to light.

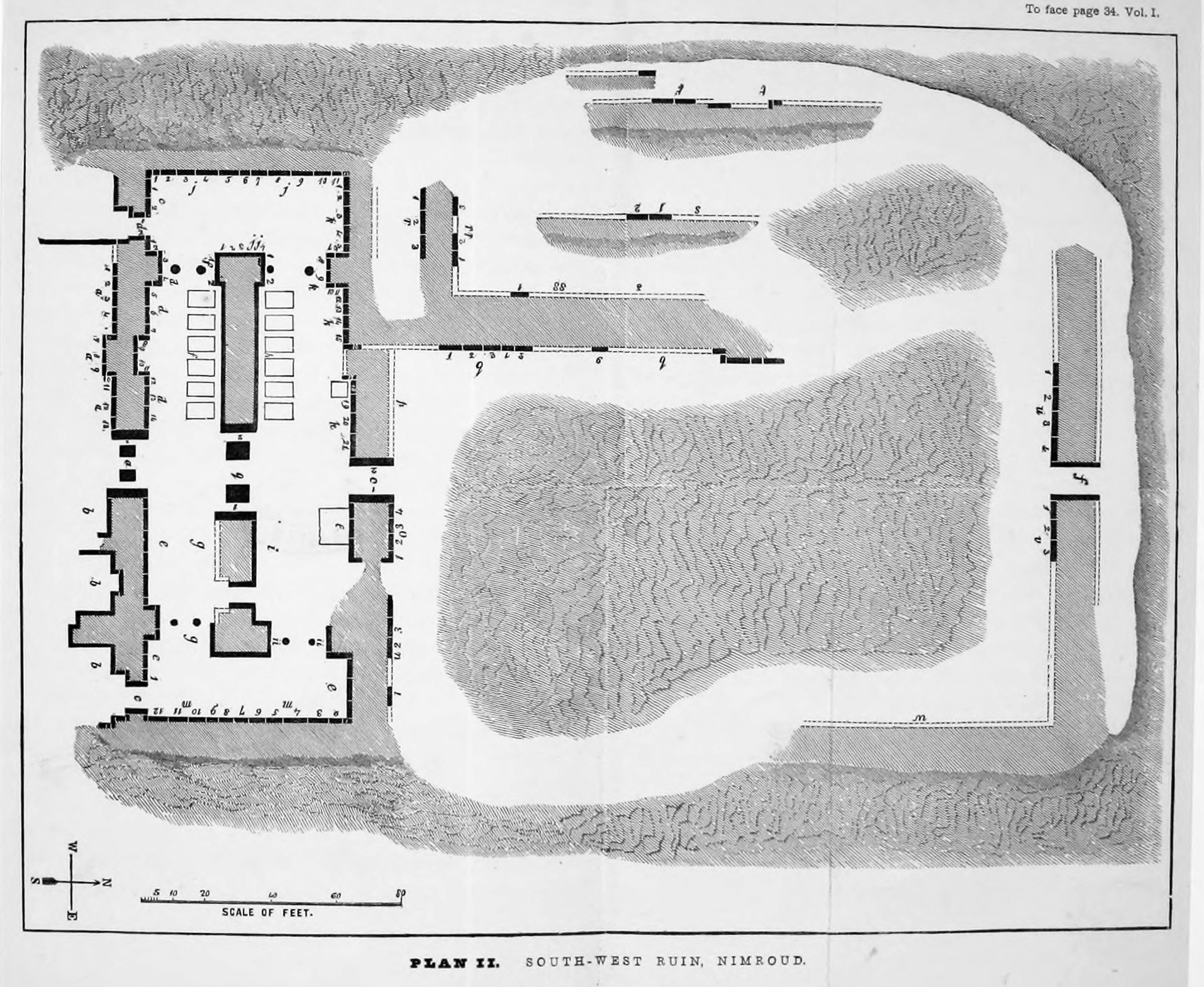

Having finished my arrangements in Mosul, I returned to Nimroud on the 19th. During my absence, the workmen, under the direction of my cawass, had carried the excavations along the back of the wall c, in plan 2., and had discovered the entrance d. Being anxious to make as much progress as possible, I increased my party to thirty men, and distributed them in three sets over the S. W. corner of the mound. By opening long trenches at right angles in various directions, we came upon the top of wall m, built of slabs with inscriptions similar to those already described. One, however (No. 10.), was reversed, and Avas covered with characters, exceeding in size any I had yet seen. On examining the inscription carefully, it was found to correspond with those of the chamber in the N. W. corner. I could not account for its strange position. The edges of this, as well as of all the other slabs in the S.W. corner, had been cut away, several letters of the inscriptions being destroyed, in order to make the stones fit into the wall. From these facts it was evident that materials taken from another building had been used in the construction of the one we were now exploring. But as yet it could not be ascertained whether the face or the back of the slabs had been uncovered. Neither the plan nor the nature of the edifice could be determined until the heap of rubbish and earth under which it was buried had been removed. The excavations were now carried on but slowly. The soil, mixed with sun-dried and kilnburnt bricks, pottery, and fragments of alabaster, offered considerable resistance to the tools of the workmen; and when loosened, had to be removed in baskets and thrown over the edge of the mound. the Chaldaeans from the mountains, strong and hardy men, could alone \vield the pick; the Arabs were employed in carrying away the earth. The spade could not be used, and there were no other means, than those I had adopted, to clear away the ruins. A person standing on the mound would see no remains of building until he approached the edge of the trenches, into which the workmen descended by steps. Parts of the walls were now exposed to view; but it was impossible to conjecture which course they took, or whether the slabs were facing the inside, or formed the back of the chamber which had probably been discovered. The Abou Salman and Tai Arabs continuing their depredations in the plains of Nimroud and surrounding country, I deemed it prudent to remove from Naifa, where 1 had hitherto resided, to Selamiyah. The latter village is built on a rising ground near the Tigris, and was formerly a place of some importance, being mentioned at a very early period as a market town by the Arab geographers, who generally connect it with the ruins of Athur or Nimroud. It probably occupied an ancient site, and in a line of mounds, now at a considerable distance from the village, but enclosing it, can be traced the original walls. Even five years ago Selamiyah was a flourishing village, and could furnish 150 well-armed horsemen. The Pasha had, however, plundered it; and the inhabitants had fled to the mountains or into the Baghdad territories. At that time ten miserable huts stood in the midst of the ruins of bazaars and streets surrounding a kasr or palace, belonging to the family of the old hereditary Pashas, well built of Mosul alabaster, but rapidly falling into decay. I had intended to take possession of this building, which was occupied by a few Hytas or irregular troops; but the rooms were in such a dilapidated condition that the low mud hut of the Kiayah appeared to be both safer and warmer. I accordingly spread my carpet in one of its corners, and giving the owner a few piastres to finish other dwelling-places which he had commenced, established myself for the winter. The premises, which were speedily completed, consisted of four hovels, surrounded by a wall built of mud, and covered in with reeds and boughs of trees plastered over with the same material. I occupied half of the largest habitation, the other half being appropriated to various domestic animals, — cows, bullocks, and other beasts of the plough. We were separated by a wall; in which, however, numerous apertures served as a means of communication. These I studiousty endeavoured for some time to block up. A second hut was devoted to the wives, children, and poultry of my host; a third served as kitchen and servants' hall: the fourth was converted into a stall for my horses. In the enclosure formed by the buildings and the outer wall, the few sheep and goats which had escaped the rapacity of the Pasha, congregated during the night, and kept up a continual bleating and coughing until they were milked and turned out to pasture at day-break. The roofs not being constructed to exclude the winter rains now setting in, it required some exercise of ingenuity to escape the torrent which descended into ray apartment. I usually passed the night on these occasions crouched up in a corner, or under a rude table which 1 had constructed. The latter, having been surrounded by trenches, to carry off the accumulating waters, generally afforded the best shelter. My Cawass, who was a Constantinopolitan, complained bitterly of the hardships he was compelled to endure, and I had some difficulty in prevailing upon my servants to remain with me. The present inhabitants of Selamiyah, and of most of the villages in this part of the Pashalic of Mosul, are Turcomans, descendants of tribes brought by the early Turkish Sultans from the north of Asia Minor, to people a country which had been laid waste by repeated massacres and foreign invasions. In this portion of the Ottoman Empire, except in Mosul and the Mountains, there is scarcely a vestige of the ancient population. The tribes which inhabit the Desert were brought from the Jebel Shammar, in Kedjd, almost within the memory of man. The inhabitants of the plains to the east of the Tigris are mostly Turcomans and Kurds, mixed with Arabs, or with Yezidis, who are strangers in the land, and whose origin cannot easily be determined. A few Chaldaeans and Jacobite Christians, scattered in Mosul and the neighbouring villages, or dwelling in the most inaccessible part of the Mountains, their places of refuge from the devastating bands of Tamerlane, are probably the only descendants of that great people which once swayed, from these plains, the half of Asia. The Yuz-bashi, or captain of the irregular troops, one Daoud Agha, a native of the north of Asia Minor, came to call upon me as soon as I was established in my new quarters. Like most men of his class, acknowledged freebooters7, he was frank and intelligent. He tendered me his services, entertained me with his adventures, and planned hunting expeditions. A few presents secured his adherence, and he proved himself afterwards a very useful and faithful aUy. I had now to ride three miles every morning to the mound; and my workmen, who were afraid, on account of the Arabs, to live at Naifa, returned, after the day's labour, to Selamiyah. The excavations were still carried on as actively as the means at my disposal would permit. The entrance, d (plan 2.), had now been completely exposed, and the backs of several slabs of wall d had been uncovered. On them were the usual inscriptions and the corner-stone (No. 4.), which had evidently been brought from another building, was richly ornamented with carved flowers and scroll-work. But still no sculptures had been discovered; nor could any idea be yet formed of the relative position of the walls. I ordered a trench to be opened obliquely from the entrance (d) into the interior of the mound, presuming that we should ultimately find the opposite side of the chamber, to which, it appeared probable, we had found the passage. After removing a large accumulation of earth mixed with charcoal, charred wood and broken bricks, we reached the top of wall f, on the afternoon of the 28th November. In order to ascertain whether we were in the inside of a chamber, the workmen were directed to clear away the earth from both sides of the slabs. The south face was unsculptured, but the first stroke of the pick on the opposite side, disclosed the top of a bas-relief. The Arabs were no less excited than myself by the discovery; and notwithstanding a violent shower of rain, working until dark, they completely exposed to view two slabs (Nos. 1. and 2.). On each slab were two bas-reliefs, separated from one another by a band of inscriptions. The subject on the upper part of No. 1. was a battle scene. Two chariots, drawn by horses richly caparisoned, were each occupied by a group of three warriors; the principal person in both groups was beardless, and evidently an eunuch. He w^as clothed in a complete suit of mail, and wore a pointed helmet on his head, from the sides of which fell lappets covering the ears, the lower part of the face, and the neck. The left hand, the arm being extended, grasped a bow at full stretch; whilst the right, drawing the string to the ear, held an arrow ready to be discharged. A second warrior urged, with the reins and whip to the utmost of their speed, three horses, who were galloping over the plain. A third, without helmet, and with flowing hair and beard, held a shield for the defence of the principal figure Under the horses' feet, and scattered about the relief, were the conquered, Avounded by the arrows of the conquerors. I observed with surprise the elegance and richness of the ornaments, the faithful and delicate delineation of the limbs and muscles, both in the men and horses, and the knowledge of art displayed in the grouping of the figures, and the general composition. In all these respects, as well as in costume, this sculpture appeared to me not only to differ, but to surpass the bas-reliefs of Khorsabad. I traced also in the character used in the inscription a marked difference from that found on the monuments discovered by M. Botta. Unfortunately, the slab had been exposed to fire, and was so much injured that its removal was hopeless. The edges had, moreover, been cut away, to the injury of some of the figures and of the inscription; and as the next slab (No. 2.) was reversed, it was evident that both had been brought from another building. This fact rendered any conjecture, as to the origin and form of the edifice we were exploring, still more difficult. The lower bas-relief on No. 2. represented the siege of a castle or of a walled city. To the left were two warriors, each holding a circular shield in one hand, and a short sword in the other. A tunic, confined at the waist by a girdle, and ornamented with a fringe of tassels, descended to the knee; a quiver was suspended at the back, and the left arm was passed through the bow, which was thus kept by the side, ready for use. They wore the pointed helmets before described. The foremost warrior was ascending a ladder placed against the castle. Three turrets, with angular battlements, rose above walls similarly ornamented. In the first turret were two warriors, the one in the act of discharging an arrow, the other raisins; a shield and castinof a stone at the assailants from whom, the besieged were distinguished by their headdress, — a simple fillet binding the hair above the temples. Their beards, at the same time, were less carefully arranged. The second turret was occupied by a slinger preparing his sling. In the interval between this turret and the third, and over an arched gateway, was a female figure, known by her long hair descending upon the shoulders in curls. Her right hand was elevated as if in the act of asking for mercy. In the third turret were two more of the besieged, the first discharging an arrow, the second elevating his shield and endeavouring with a torch to burn an instrument resembling a catapult, which had been brought up to the wall by an inclined plane built on a heap of boughs and rubbish. These figures were out of all proportion when compared with the size of the building. A warrior with a pointed helmet, bending on one knee, and holding a torch in his right hand, was setting fire to the gate of the castle, whilst another in full armour was forcino; the stones from the foundation with an instrument, probably of iron, resembling a blunt spear. Between them was a wounded man falling headlong from the walls. No. 2. was a corner-stone very much injured, the greater part of the relief having been cut away to reduce it to convenient dimensions. The upper part, being reversed, was occupied by two warriors; the foremost in a pointed helmet, riding on one horse and leading a second; the other, without helmet, standing in a chariot, and holding the reins loosely in his hands. The horses had been destroyed, and the marks of the chisel were visible on many parts of the slab, the sculpture having been in some places carefully defaced. The lower bas-relief represented a singular subject. On the walls of the castle, two stories high, and defended by many towers, stood a woman tearing her hair to show her grief. Beneath and by the side of a stream, figured by numerous undulating lines, crouched a fisherman drawing from the water a fish he had caught. This slab had been exposed to fire like that adjoining, and had sustained too much injury to be removed. As I was meditating in the evening over my discovery, Daoud Agha entered, and seating himself near me, delivered a long speech, to the effect, that he was a servant of the Pasha, who was again the slave of the Sultan; and that servants were bound to obey the commands of their master, however disagreeable and unjust they might be. I saw at once to what this exordium was about to lead, and was prepared for the announcement, that he had received orders from Mosul to stop the excavations by threatening those who were inclined to work for me. On the following morning, therefore, I rode to the town, and waited upon his Excellency. He pretended to be taken by surprise, disclaimed having given any such orders, and directed his secretary to write at once to the commander of the irregular troops, who was to give me every assistance rather than throw impediments in my way. He promised to let me have the letter in the afternoon before I returned to Selamiyah; but an officer came to me soon after, and stated that as the Pasha was unwilling to detain me he would forward it in the night. I rode back to the village, and acquainted Daoud Agha with the result of my visit. About midnight, however, he returned to me, and declared that a horseman had just brought him more stringent orders than any he had yet received, and that on no account was he to permit me to carry on the work. Surprised at this inconsistency, I returned to Mosul early next day, and again called upon the Pasha. "It was with deep regret," said he, "I learnt, after your departure yesterday, that the mound in which you are digging had been used as a burying-ground by Mussulmans, and was covered with their graves; now you are aware that by the law it is forbidden to disturb a tomb, and the Cadi and Mufti have already made representations to me on the subject." "In the first place," replied I, " being pretty well acquainted with the mound, I can state that no graves have been disturbed; in the second, after the wise and firm 'politica' which your Excellency exhibited at Sivas, grave-stones would present no difficulty. Please God, the Cadi and Mufti have profited by the lesson which your Excellency gave to the ill-mannered Ulema of that city." "In Sivas," returned he, immediately understanding my meaning, "I had Mussulmans to deal with, and there was tanzimat8, but here we have only Kurds and Arabs, and, Wallah! they are beasts. Xo, I cannot allow you to proceed; you are my dearest and most intimate friend: if anything happens to you, what grief should I not suffer! your life is more valuable than old stones; besides, the responsibility would fall upon my head." Finding that the Pasha had resolved to interrupt my proceedings, I pretended to acquiesce in his answer, and requested that a Cawass of his own might be sent with me to Nimroud, as I wished to draw the sculptures and copy the inscriptions which had already been uncovered. To this he consented, and ordered an officer to accompany me. Before leaving Mosul, I learnt with regret from what quarter the opposition to my proceedings chiefly came. On my return to Selamiyah there was little difficulty in inducing the Pasha's Cawass to countenance the employment of a few workmen to guard the sculptures during the day; and as Daoud Agha considered that this functionary's presence relieved him from any further responsibility, he no longer interfered with any experiment I might think proper to make. Wishing to ascertain the existence of the graves, and also to draw one of the bas-reliefs, which had been uncovered, though not to continue the excavations for a day or two, I rode to the ruins on the following morning, accompanied by the Hytas and their chief, who were going their usual rounds in search of plundering Arabs. Daoud Agha confessed to me on our way that he had received orders to make graves on the mound, and that his troops had been employed for two nights in bringing stones from distant villages for that purpose.9" We have destroyed more real tombs of the true Believers," said he, " in making sham ones, than you could have defiled between the Zab and Selamiyah. We have killed our horses and ourselves in carrying those accursed stones." A steady rain setting in, I left the horsemen, and returned to the village. In the evening Daoud Agha brought back with him a prisoner and two of his followers severely wounded. He had fallen in with a party of Arabs under Sheikh Abd-ur-rahman of the Abou Salman, whose object in crossing the Zab had been to plunder me as I worked at the mound. After a short engagement, the Arabs were compelled to recross the river. I continued to employ a few men to open trenches by way of experiment, and was not long in discovering other sculptures. Near the western edge we came upon the lower part of several gigantic figures, uninjured by fire,10 It was from this place that in the time of Ahmed Pasha, materials were taken for rebuilding the tomb of Sultan Abdallab, and the slabs had been sawn in half, and otherwise injured. At the foot of the S. E. corner was found a crouching lion, rudely carved in basalt, which appeared to have fallen from the building above, and to have been exposed for centuries to the atmosphere. In the centre of the mound we uncovered part of a pair of gigantic winged bulls, the head and half the wings of which had been destroyed. On the back of the enormous slabs, the length of which was fourteen feet, whilst the height must have been originally the same, on which these animals had been carved in high relief, were inscriptions in large and well-cut characters. A pair of small winged lions11, the heads and upper part destroyed, were also discovered. They appeared to form an entrance into a chamber, were admirably designed and very carefully executed. Finally, a human figure, nine feet high, the right hand elevated, and carrying in the left a branch with three flowers, resembling the poppy, was found in wall k (plan 2.). I uncovered only the upper part of these sculptures, satisfied with proving their existence, without exposing them to the risk of injury, should my labours be at any time interrupted. Still no conjecture could be formed as to the contents of the mound, or as to the nature of the buildings I was exploring. Only detached and unconnected walls had been discovered, and it could not even be determined which side of them had been laid bare. The experiment had been fairly tried; there was no longer any doubt of the existence not only of sculptures and inscriptions, but even of vast edifices in the interior of the mound of Nimroud, as all parts of it that had yet been examined, furnished remains of buildings and carved slabs. I lost no time, therefore, in acquainting Sir Stratford Canning with my discovery, and urging the necessity of a Firman, or order from the Porte, which would prevent any future interference on the part of the authorities, or the inhabitants of the country. It was now nearly Christians, and as it was desirable to remove all the tombs, which had been made by the Pasha's orders, on the mound, and others, more genuine, which had since been found, I came to an understanding on the subject with Daoud Agha. I covered over the sculptures brought to light, and withdrew altogether from Nimroud, leaving an agent at Selamiyah. On entering Mosul on the morning of the 18th, I found the whole population in a ferment of joy. A Tatar had that morning brought from Constantinople the welcome news that the Porte, at length alive to the wretched condition of the province, and to the misery of the inhabitants, had disgraced the governor, and named Ismail Pasha, a young Major General of the new school, to carry on affairs until Hafiz Pasha, who had been appointed to succeed Keritli Oglu, could reach his government. Only ten days previously the inhabitants had been well-nigh driven to despair by the arrival of a Firman, confirming Mohammed Pasha for another year; but this only proved a trick on the part of the secretaries of the Porte to obtain the presents which are usually given on these occasions, and which the Pasha, on receipt of the document, hastened to remit to Constantinople. His Excellency was consequently doubly aggrieved by the loss of his Pashalic and of his money. Ismail Pasha, who had been for some time in command of the troops at Diarbekir, had gained a great reputation for justice amongst the Mussulmans, and for tolerance amongst the Christians. Consequently his appointment had given much satisfaction to the people of Mosul, who were prepared to receive him with a demonstration. However, his Excellency slipped into the town during the night, some time before he had been expected. On the following morning a change had taken place at the Serai, and Mohammed Pasha, with his followers, were reduced to extremities. The drao;oman of the Consulate, who had business to transact with him, found the late Governor sitting in a dilapidated chamber, through which the rain penetrated without hindrance. " Thus it is," said he, " with God's creatures. Yesterday all those dogs were kissing my feet; to-day every one, and everything, falls upon me, even the rain! " During these events the state of the country rendered the continuation of my researches at Nimroud almost impossible. I determined, therefore, to proceed to Baghdad, to make arrangements for the removal of the sculptures at a future period, and to consult generally with Major Rawlinson, from whose experience and knowledge I could derive the most valuable assistance. A raft having been constructed, I started with Mr. Hector, a gentleman from Baghdad, who had visited me at Nimroud, and reached that city on the 24th of December.

|

|

|

|

|

1) Literally, "tooth-money." 2) To eat money, i. e. to get money unlawfully or by pillage, is a common expression in the East. 3) Mr. Ross will perhaps permit me to acknowledge in a note, the valuable assistance I received from him, during my labours in Assyria. His knowledge of the natives, and intimate acquaintance with the resources of the country, enabled him to contribute much to the success of my undertaking; whilst to his friendship I am indebted for many pleasant hours, which would have been passed wearily in a land of strangers. 4) Tills and similar traditions are found in a work called Kusset el Nimroud, (Stories of Nimrod,) which Rich represents the inhabitants of the villages near the ruins, as reading during the winter nights. Although there is no one in these days within some miles of the place who possesses the work, or could read it if he did, the tales it contains are current amongst the Arabs of the neighbourhood. I heard of several MSS. of the Kusset at Mosul; but as they are classed amongst religious volumes, I was unable to procure a copy. (See note in chap. xxi. of Sale's Koran, for a story somewhat similar to that in the text.) 5) This was the chamber marked A on the plan. 6) Back of wall j, plan 2. 7) The Irregular cavalry, [Hytas as they are called in this part of Turkey, and Bashi-bozuks in Roumelia and Anatolia,] are collected from all classes and provinces. A man, known for his courage and daring, is named Hyta-Bashi, or chief of the Hytas, and is furnished with teskérés, orders for pay and provisions, for so many horsemen, from four or five hundred to a thousand or more. He collects all the vagrants and freebooters he can find to make up his number. They must find their own arms and horses, although sometimes they are furnished by the Hyta-bashi, who deducts a part of their pay until he reimburses himself. The best Hytas are Albanians and Lazes, and they form a very effective body of irregular cavalry. Their pay at Mosul is small, amounting to about eight shillings a month; in other provinces it is considerably more. They are quartered on the villages, and are the terror of the inhabitants, whom they plunder and ill-treat as they think fit. When a Hyta-bashi has established a reputation for himself, his followers are numerous and devoted. He wanders about the provinces, and like a condottiere of the middle ages, sells his services, and those of his troops, to the Pasha who offers most pay, and the best prospects of plunder. 8) The reformed system introduced into most provinces of Turkey, but which had not yet been extended to Mosul and Baghdad. 9) In Arabia, the graves are merely marked by unhewn stones placed upright at the head and feet, and in a head over the body, 10) Wall t, in plan 2. 11) Entrance to chamber BB, plan 3.

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD