By-Paths of Bible Knowledge

Book 10 - The Trees and Plants Mentioned in the Bible

Henry Chichester Hart, B.A. (T.C.D.), F.L.S.

T - W

|

PERFUMES AND MEDICINES.

THE productions now to be considered, though interesting in many respects,

differ in some particulars from those noticed in the preceding chapters. They

are, for the most part, vegetable extracts or secretions, and of foreign growth

so far as the Jews were concerned, having been imported in ancient times from

the Farther East, and conveyed by travelling caravans into Egypt and Southern

Europe by way of Syria and Palestine. This circumstance is illustrated by the

general similarity of the Hebrew and classical names. A few, but only a few,

were indigenous to Canaan. As, however, these productions form a part of 'Bible

botany,' though mostly excluded from the flora of Palestine and the adjacent

countries, they demand a brief notice here on account of their former

importance, and the value attached to them by the perfume-loving Orientals. Of this last fact, Scripture affords both direct and indirect evidence; among the latter, the numerous words found in the Old Testament denoting 'incense,' 'spices,' 'ointments,' and perfumes,' and the ingredients of which these precious com-pounds were formed. They entered into the ritual of Divine worship, and the ceremonies of state, were used as articles of customary adornment, or of special honour or indulgence; they alleviated sickness and suffering; and were alike tokens of consideration for the living and affection for the dead.

The chief element in these preparations, whether for sacred or secular purposes, was olive oil (Deut. xxviii. 40; Micah vi. 5), he words 'oil' and 'ointment' being interchangeable. Probably myrrh ranked next in importance (Esther ii. 12). The 'ointment' of the New Testament is μύρον, the same word as the Hebrew מׂר mor, while o-σμύρνα denotes myrrh itself. It was from Egypt, and not from Greece or Italy, that the Hebrews derived their knowledge of these productions. Indeed, they carried the knowledge with them to the land of their inheritance, through which the stream of commerce passed to the banks of the Nile; for at a period earlier than the Exodus, a trade with India and the Far East, through Arabia, had been established (Gen. xxxvii. 25). We know moreover, both from history and the monuments, that the Egyptian people delighted in perfumes as well as in flowers, as articles of luxury and festive enjoyment. Guests were not only decked with garlands, but also anointed by attendants with sweet-scented ointments poured from vases of glass, alabaster, or porcelain. The apartments were also filled with the perfume of myrrh, frankincense, and other aromatics. Incense, composed of myrrh, resin, and other ingredients, was presented to 'all the gods on all important occasions,' and odoriferous substances were enclosed within the bodies of animals offered in sacrifice. The use of spices, such as cinnamon and myrrh, in the process of embalming, as among the agents employed to counteract decay, is also a well-known fact. This duty was performed under the superintendence of the medical class, for Egypt is regarded as the cradle of the healing art 'The physicians embalmed Joseph,' and as students of the human frame and its disorders they would be the first to form a materia medica. 'O virgin, the daughter of Egypt,' the prophet Jeremiah exclaims, 'in vain shalt thou use many medicines, for thou shalt not be cured' (ch. xlvi. II). Job says of his friends, 'Ye are all physicians of no value' (ch. xiii. 4), another evidence of Egyptian elements in that ancient poem, side by side with the 'behemoth' and 'leviathan' of the Nile. The fame of those learned predecessors of Galen and Hippocrates reached to Persia on the one hand, and to Rome on the other; and Homer makes Helen ascribe her knowledge of drugs of sovereign value to an Egyptian queen1. These facts explain and illustrate many allusions in the Old Testament to such products of the East as were used by the Hebrews long before Rome had been shorn of her early strength and simplicity. The ' apothecary's art,' first named in the Book of Exodus (xxx. 25, 35) in connexion with the 'incense' and 'holy anointing oil' of the Tabernacle, probably had its rise in the duties of religious worship, just as the Greeks anciently dedicated flowers to the gods. Centuries before the reverent piety of the Jewish rabbi embalmed the body of the crucified Saviour with a profusion of 'myrrh and aloes,' 'as the manner of the Jews' was 'to bury,' King Asa had been laid to rest in a couch 'filled with sweet odours and divers kinds of spices prepared by the apothecaries' art,' while 'a very great burning' of like perfumes 'was made for him' (2 Chron. xvi. 14). A 'son of one of the apothecaries' is mentioned by Nehemiah (iii. 8) among those who returned from the Babylonish captivity. From the allusions in the Gospels we find that in the obsequies of the dead, at least those of the wealthier classes, the custom was to anoint the body with ointments, and then to wrap it in folds of linen with aromatic spices (cf. Matt. xxvi. 12; Mark xvi. i; Luke xxiii. 56; John xix. 39, 40). As articles of luxury, ointments and perfumes belong chiefly to the period of the Jewish monarchy, and of course to later times, such as those of the New Testament. Before Solomon's reign, the anointing of the person seems to have been limited to the application of olive oil, as befitted those simpler days. 'Thou shalt have olive trees, but thou shalt not anoint thyself with the oil,' is the language of Moses in the Book of Deuteronomy (xxviii. 4o). So Ruth, David, and others are spoken of (Ruth iii. 3; 2 Sam. xii. 20; Psalm xxiii. 5, &c.). In the Proverbs, and in succeeding writings of the Old Testament, allusions to the use, and still oftener to the abuse, of perfumes and ointments are not infrequent (see Psalm cxxxiii. 2; Prov. vii. 17; xxvii. 9, 16; Eccles. vii. z; Song of Solomon i. 3; iii. 6; iv. 10; Isaiah lvii. 9; Amos vi. 6). In the New Testament these precious compounds appear among the gifts bestowed upon the Saviour by grateful affection, and finally in the Book of Revelation as part of the merchandise of the mystic Babylon (Luke vii. 37; Matt. xxvi. 7; Rev. xviii. 13). While, however, the existence of 'physicians,' as a class, is distinctly recognized in Scripture, the references to specific medicines and medicinal applications are too few and slight to afford any definite information. But it would seem that they resembled the agencies now in use in Eastern countries. Oil, ointment, a mixture of oil and wine (as in the parable of the Good Samaritan), balm of Gilead, poultices of figs, wine as a restorative, wine and myrrh as an opiate, and the leaves of trees (Ezek. xlvii. 12; Rev. xxii. 2), appear to be the chief allusions to medicinal appliances, internal or external. But others were doubtless in use both in Old and New Testament times. Both the Greeks and the Romans indulged in the use of perfumes; the former from a very early period, the latter not until the rude simplicity of the earlier republic had disappeared before advancing wealth and refinement, and the way prepared for the degrading Sybaritism of imperial times. Homer's feasts are primitive even to rudeness, but his heroes and heroines are anointed with perfumed ointments. Guests were supplied with perfumed soap for washing, both before and after a meal; oil was a necessary adjunct of the gymnasia, and it was used in funereal observances both before and after the burning of the corpse. Both Greeks and Romans had their perfume and spice boxes and bottles (alabastra), and the wealthier among them carried their caskets about with them, as is done in India at the present day2. Among the Romans ointments were used in place of soap, until the introduction of the latter; they were applied before and after bathing, and the bathers' garments were scented. For these preparations extracts of native flowers were employed, or costly Oriental ingredients kept in bottles of stone or precious metal. The ashes of the dead were also mixed with scents; while at the obsequies of an emperor, incense, spices, and fragrant herbs formed part of the funeral pyre. In the numerous allusions to these vegetable substances in the writings of classical poets they are frequently described as Assyrian' (i.e. Syrian), 'Arabian,' or 'Sabaean,' indicating the direction in which they were brought to Italy, Persia and India are also mentioned. ALOES (Heb. אֲהָלִים ahalim, אֲהָלוֹת ahaloth; Gk. ἀλόη)

The ALOES of Scripture bear no relation to the flowering aloe of modern gardens, but represent an odoriferous wood which from a remote period has been known and used in the East both for sacred and common purposes. This 'aloes wood,' corrupted into 'eagle wood' (Lignum aquilae), and called in Numb. xxiv. 6, 'lign aloes,' is yielded by two different kinds of trees; the one (Aloexylon agallochum) a native of Cochin China, the other (Aquilaria agallochum) is indigenous to India. The latter is most probably the one known to the ancient Hebrews, and its Malayan name agila is reproduced as ahalim. This tree reaches a height of more than a hundred feet, and is said to yield its fragrance when decay has commenced. To the same species Rosenmuller apparently refers when he says, 'The Indians regard the tree as sacred, and never cut it down without various religious ceremonies. The people of the East suppose it to have been one of the indigenous trees of Paradise, and hence the Dutch give it the name of Paradise-tree.' It is mentioned by Dioscorides, who says it was a spotted odoriferous wood which was brought from India and Arabia. The Orientals burn this or some similar wood in their apartments, as a mark of honour to visitors. Aloes are referred to four times in the Old Testament, and once in the New. Balaam compares the tents of the Israelites to 'lign aloes' by the river Tigris or Euphrates. Here the allusion may be to some aromatic shrub indigenous to Babylonia, just as 'myrtle' and 'myrrh' were sometimes denoted by the same word. In Psalm xlv. 8; Song of Solomon iv. 14; and Proverbs vii. 17 aloes are associated with myrrh as agreeable and attractive per-fumes; while in the New Testament they appear but once, and then in connection with the burial of the Saviour by Joseph and Nicodemus. The fullest notice of the plants above mentioned will be found in Kitto's Cyclopaedia (art. Ahalim), by the late Dr. Royle. BALM (Heb. צֳרִי Tseri, צְרִי tsori)

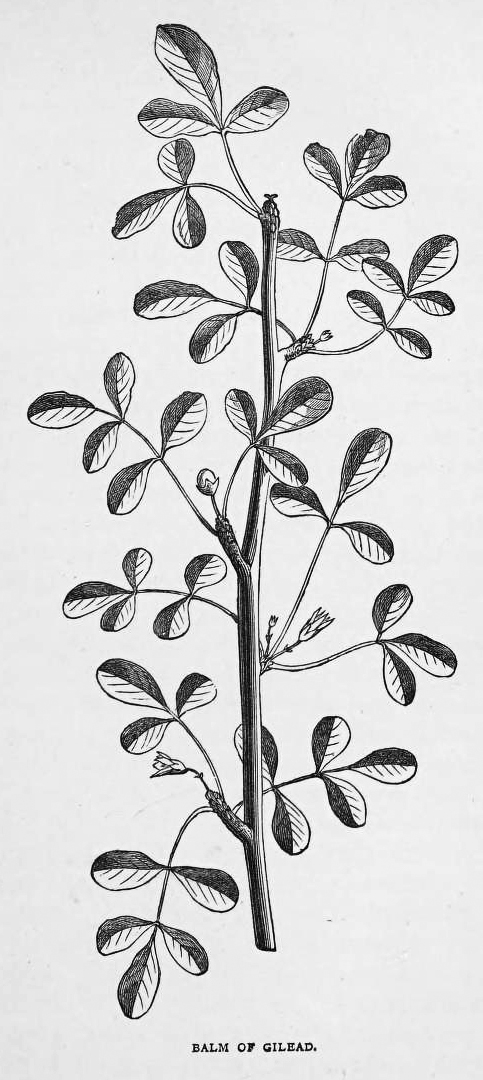

This far-famed product of Eastern Palestine is mentioned by both Jewish and classical writers. Josephus informs us in his Antiquities and Wars of the Jews that the balm or balsam tree grew in the region round about Jericho, of which it was the most costly and valued product; that the secretion was obtained by making an incision in the plant with a sharp stone; and that it was the general belief that the original root from which these trees had sprung was the gift of the Queen of Sheba to Solomon. But it seems that even in patriarchal times balm was exported from Gilead to Egypt, where, at a later period, it is said to have been cultivated, especially at Heliopolis, the ancient On. Jacob deemed it an acceptable gift to his unknown son (Gen. xliii. II). In Ezekiel's day (ch. xxvii. 17) the Israelites took this product of their land into the markets of Tyre. The prophet Jeremiah mentions balm three times, twice locating it in Gilead: 'Is there no balm in Gilead?' 'Go up to Gilead, and take balm;' 'Take balm for her pain' (ch. viii. 22; x1vi. 11; li. 8). In the tropical valley of Jordan, and on both sides of the river, this celebrated shrub grew, and was diligently cultivated, at whatever time it may have been originally introduced. It is indigenous in Arabia and Nubia. The genus Balsamodendron, which yields both balm and myrrh, includes several species; from one (B. opobalsamum), or probably from more than one, the Balm of Gilead, or Opobalsamum, is obtained by incisions in the bark. Inferior extracts are obtained from the branches, by boiling and skimming, and from the fruit, by pressure. These shrubs or trees, which bear winged leaves and small flowers, are alluded to by Pliny and Diodorus, and by the botanists Theophrastus and Dioscorides3. Alexander the Great is said to have recognized the value of the precious gum, and Vespasian and Titus caused specimens of the trees to be exhibited at Rome. They also placed the gardens under proper supervision, and these plantations existed until the time of the Crusades. The balsam tree, however, like the date palm, has long since disappeared from Jericho and Gilead. BDELLIUM (Heb. בְּדׂלַח bedolach).

There has been much dispute as to the meaning of the Hebrew word translated BDELLIUM, some interpreters placing it in the mineral kingdom and identifying it with the pearl, while others regard it as a gum resin. It is mentioned only in the passages above quoted, and while we infer from comparing Numb. xi. 7 with Exod. xvi. 31 that bdellium was white in colour, we do not know with any certainty where the land of Havilah was situated. In default of ampler evidence, we may accept the statement of Josephus, who says of the manna, that it was like in its body to bdellium, one of the sweet spices4.' If so, we may group it with balm and myrrh as the produce of an Indian species of Balsamodendron, and which Moses would have become acquainted with in Egypt. CALAMUS, 'SWEET CANE' (Heb. קָנֶה kaneh, Gk. κάλαμος).

The above passages are cited together because they give all the information to be gathered from Scripture on the subject; CALAMUS is but Latin for 'cane'—the Hebrew kaneh, and the latter word occurs in all of them. It is the ordinary term for reed or cane, but its specific character and application are indicated by the context. All, however, that we know of Calamus, Sweet Calamus, or Sweet Cane amounts to this, that the 'sweetness' was sweetness of odour and not of taste, and that it was brought from a 'far country,' presumably from Sheba or some part of Arabia. Its native source and locality are unknown, and Josephus only says, 'It is a sort of sweet spice.' Such fragrant grasses as the Andropogon of India, and the Sugar-cane, have been suggested; but the Calamus was aromatic, and no grasses are exported from India (according to Sir G. Birdwood) for such purposes. Both Pliny and Dioscorides, however, mention an 'aromatic cane' as growing in India. Sir G. Birdwood is disposed to identify the above with the root of a composite plant known as Costus or 'Indian orris' (Aucklandia costus), a native of the highlands of Cashmere. CASSIA (Heb. קִדָּה kiddah, קְצִיעוֹת ketsioth). CINNAMON (Heb. קִנָּמוֹן kinnanon, Gk. κιννάμωμον).

The above substances are connected by close botanical affinities, being produced by nearly the same trees, and applied to the same uses. Both belong to the class of aromatic barks, and both are familiar spices in our own country, though CINNAMON is more frequently recognized than CASSIA. Although products of the Far East—the island of Ceylon, Cochin China, and the Malabar Coast—they have been known from a remote period in Palestine, and probably in Egypt also. They arc mentioned by Herodotus as Arabian products—an error common to Greek writers in relation to plants which reached Europe viā the Arabian ports—and he gives an absurd account of the mode of collecting each. Cinnamon and cassia belong to the family which includes the bay tree, the camphor tree, and other aromatics. The former is the bark of Cinnamomum Zeylanicum, a native of Ceylon, where it grows to a considerable size. The leaves are smooth and leathery, and strongly ribbed, and the flowers are grouped in clusters of greenish white. When the tree is about five years old the branches are lopped, in the summer months, and the bark peeled off in longitudinal strips and rolled up—the smaller quills within the larger ones. CASSIA is native in Cochin China, and is the bark of C. aromaticum; but inferior cinnamon is largely exported as cassia, which naturally is of a thicker substance. Both these products are strongly aromatic, but the scent of cassia is more pungent and less agreeable than that of cinnamon. The odour-loving Orientals would probably distinguish readily between them. They are employed in medicine as stimulants and carminatives, in various forms, such as oil, tincture, and aqueous solution. Cinnamon and cassia are enumerated in Exodus xxx. 23, 24, among the 'principal spices' in the directions given for compounding the 'anointing oil' of the sanctuary. The garments of the royal bride in Psalm xlv. 8 are said to 'smell of myrrh, aloes, and cassia,' or' cassias,' perhaps cinnamon and cassia being united in the word ketsioth, which resembles kiddah, the term used elsewhere. 'Cinnamon' is among the perfumes mentioned in the house of the 'strange woman' of Proverbs vii. 17, and among the exotic plants growing in the 'garden enclosed' described in the fervid imagery of the Song of Solomon (iv. 14). We may infer that many such foreign plants were introduced by Solomon, though they probably died out in the course of succeeding and less tranquil reigns. It is named but once in the New Testament, as part of the merchandise of 'Great Babylon' (Rev. xviii. 13). CADIPHIRE (Heb. כּׂפֶר kopher).

With these passing and emblematic references in one short poem, begins and ends all Biblical recognition of a plant 'universally esteemed in Eastern countries,' and which 'appears to have been so from the earliest times, both on account of the fragrance of its flowers, and the colouring properties of its leaves.' It is the shrub known to the Arabs as al-henna, the HENNA PLANT of travellers and the Kl'nTpos of Greek writers. Pliny says that the best kind grows on the banks of the Nile; the second best at Ascalon of Judea; the third, and most sweet in odour, in 'Cyprus,' from which its Greek name was derived. This circumstance will explain the marginal readings in the Author-ized Version of the above passages, which have 'or cypress;' not, however, alluding to the noble conifer properly so called, but to the plant now under consideration. It is the Lawsonia alba of botanists, a tall shrub six or eight feet in height, with pale green foliage, and clusters of white and yellow blossoms, which emit a delightful perfume. It grows in Egypt and Nubia, and also in Arabia, and is still to be found near the Dead Sea at Engedi, as in Solomon's time. It is one of the most favourite flowers and cosmetics of the Eastern world, from India (of which country it is a native) to Turkey. Houses are perfumed with it, the blossoms are presented to guests as a marked compliment, and women use the henna flower as a personal ornament. In India the blossoms are offered to the Buddhist deities. The tropical Jordan valley would afford a congenial climate for the growth of the Lawsonia, which needs considerable care for its successful culture, even in Egypt, where it was known and used in ancient as it is in modern times. But the henna plant has been applied to another purpose throughout the East, viz. as a dye for the hands, feet, and nails. The leaves are dried and pounded and made into a paste, which when applied to the skin produces an orange or reddish tint, which is much esteemed. The practice prevails from the Ganges to the Mediterranean, and in some parts is applied to the hair of the beard and to the manes and tails of horses. The tint is deepened to black, if desired, by the application of indigo. Evidences of this widespread and, to our taste, repulsive fashion exist in the appearance of the nails of some of the Egyptian mummies. But no reference to it occurs in Scripture, unless, as Dr. Harris has suggested, the phrase in Deut. xxi. 12 'pare her nails' may bear that meaning. The Lawsonia belongs to the same order of plants (Lythraceae) as the 'loosestrifes' of our riversides. FRANKINCENSE (Heb. לְֹבוֹנָה lebonah, Gk. λίβανος)

The English name of this celebrated perfume, the odour of which arose continually from Hebrew altars, and which was deemed a fitting gift to One who was 'greater than the temple,' is somewhat misleading. One would suppose it to be, like ordinary incense, a compound, whereas it is a simple ingredient, as is evident from Exod. xxx. 34, 35, where it is ordered to be mixed with 'stacte, and onycha, and galbanum,' and from Song of Solomon iii. 6 and iv. 6, 14, where a 'hill' and 'trees of frankincense ' are mentioned. Nor does our Authorized Version avoid the same confusion of the element and the mixture; for in six passages—three in Isaiah (ch. xliii. 23, lx. 6, and lxv. 3) and three in Jeremiah (ch. vi. 20, xvii. 26. and xli. 5)—the word lebonah, 'frankincense,' is translated incense. All these render-ings, however, are corrected in the Revised Version. FRANKINCENSE is the produce of a tree known as the Boswellia thurifera, and of several allied species or varieties. This is a tree of large size, allied to the turpentine or terebinth, and to those yielding balm and myrrh. The gum which exudes from it, known by the scarcely altered name of olibanum, is in roundish or oblong drops, of a pale red or yellow colour, and which exhale a strong balsamic odour when warmed or burnt. The Scripture references to frankin-cense, though somewhat numerous, admit of very simple classification. Out of some two and twenty, sixteen have to do with its use in religious worship; twice it is spoken of as a tribute of honour—to Israel and to Israel's infant Lord; once as an article of merchandise; and thrice as the product of the royal 'garden' of the Canticles. Probably it was almost exclusively employed in the service of the Tabernacle and Temple until Solomon's reign. In Isaiah lx. 6 it is said, 'All they from Sheba shall come; they shall bring gold and incense' (i.e. frankincense). In literal accordance with this statement, and with the all but unanimous testimony of ancient authors, and of such modern naturalists as Bochart and Celsius, the latest researches into the geographical distribution of the boswellias and their resinous products have satisfactorily shown that Arabia is the chief source of the olibanum of commerce, though there is also an African kind exported into Southern Europe. In spite of the doubts which recent authors of repute have expressed on this point, Sir G. Birdwood's researches may be considered to have set the matter at rest, and restored to the 'soft Sabaeans' the claim allowed by Virgil and other classic poets, of being the producers of the fragrant gum. As already hinted, Western writers often mistook for native Arabian products those which simply passed through that ancient emporium. But ' as to frankincense, it is always mentioned as a foreign production in Hindoo books, and to this day the people in the bazaars of Western India tell you that it comes from Arabia.' The writer just quoted has treated the subject in an interesting and exhaustive manner in Cassell's Bible Educator, vol. i. pp. 328, 374, &c., where several species of Boswellia are figured, and a map of their Arabian habitat is given. Frankincense is not mentioned by Homer, and seems not to have become known to the Greeks till a later period, when it was largely employed in the obsequies of the wealthier citizens, as it is in our day with high-caste Hindoos. It was expressly excluded, however, from the aromatics used by the Egyptians for embalming. The Greeks gave the similar name of λιβανωτίς to the fragrant rosemary, and both plants contribute to the folklore of later time—the rosemary being burnt in the chambers of the sick and carried at funerals, while frankincense was deemed a counteractive to the influence of witches—either from its association with the child Jesus, or from its powerful odour, or both. The former was deemed a specific in certain diseases; and the latter was applied externally in plaisters and given internally as a stimulant, but is now rarely used. GALBANUM (Heb. חֶלֶבְּנָה chelbenczh), ONYCHA (Heb. שְׁחֵלֶת shecheleth), STACTE (Heb. נָטָף nataph).

It savours of presumption to pronounce on the precise meaning of names used, like the above, in but a single passage of Scripture, without strong confirmatory evidence from language, history, or geography. In the present case such evidence is meagre enough. The three gums or spices above grouped together are similarly associated in the Apocrypha (Ecclus. xxiv. 15), where in evident parallel to the passage on Exodus it is said, 'It yielded a pleasant odour like the best myrrh; as galbanum and onyx and sweet storax.' This may be taken as a Jewish comment. About GALBANUM this much seems clear, that the Greeks borrowed the name from the Hebrews, and that it came to them through Syrian commerce. Gum galbanum is a waxy, brownish-yellow exudation, obtained from more than one kind of umbelliferous plant resembling fennel, either naturally or by incision. It is imported from Italy and the Levant, but the precise plant which yields it has not been satisfactorily deter-mined. Dioscorides and Pliny both mention galbanum, and say that it was from Syria—a somewhat vague 'geographical expression' with ancient writers. Its odour is powerful, and it is used in medicine, though less esteemed than formerly. Columella speaks of 'galbanean odours,' and we are told that this gum was mixed with other substances to produce a fragrant ointment. Virgil recommends his farmer to drive away snakes from the folds by the fumes of galbanum5, from which and from other allusions we may infer that galbanum was not an agreeable perfume when used alone. ONYCHA is generally supposed, though the point is uncertain, to be the operculum (or covering to the mouth) of a species of mollusk (Strombus) living in Eastern seas. The shells are used in large quantities for making cameos, and the operculum is pounded and mixed with aromatic substances. It is the 'odoriferous shell' of the ancients, but obviously does not come under the cognizance of the botanist. STACTE is the Greek translation of the Hebrew name, which signifies 'a drop.' The passage from the Apocrypha makes it equivalent to 'sweet storax,' a resin yielded by Storax officinale, a plant allied to that producing gum benzoin. The storax of commerce is not now obtained from this species; and in Southern Europe it yields no resin, but it is said to do so in Asia Minor; and we may conclude that it did so in Palestine, of which it is a native. A plant known as Liquidambar orientale, found in Cyprus and Anatolia, yields the officinal storax; this species grows in Palestine, but is considered not to be truly native there. MYRRH (Heb. מׂר mor, לׂט lot; Gk. σμύρνα).

Myrrh was anciently used as a perfume, a 'medicine, and a preservative agent in embalming the bodies of the dead; and had a reputation equal to that of any aromatic known. It was supposed to impart strength, as well as to lessen pain, and entered as an ingredient into many medicinal com-pounds. The tincture, as is well known, is still employed both internally and externally, but is reckoned of very minor importance.

Unlike frankincense, it appears in Scripture almost entirely in its secular

applications. It is mentioned once as an ingredient in the 'anointing oil' for

the Tabernacle (Exod. xxx. 23); it was presented by the Magi to the infant

Saviour; it was offered to and refused by Him when, bearing in His body our sins

on the cross, He passed through His last agony; and it formed part of the spices

in which His body was laid for the few hours preceding His glorious resurrection

(Matt. ii.

11; Mark xv. 23; John xix. 39). The remaining allusions to myrrh are exclusively

in its character as an agreeable perfume, and occur chiefly in the Canticles.

The latter references (ch.

v.

5, 13), and that in the Book of Esther (ii. 12), imply a preparation termed 'oil

of myrrh,' which we may infer consisted of the resin combined with olive oil,

like the 'anointing oil' of the Sanctuary, though of a less complex character.

A different Hebrew word

לׂט (lot) is incorrectly translated

'myrrh' in Gen. xxxvii.

25 and xliii. in the enumeration of the wares carried by the Ishmaelite traders

through Palestine to Egypt, and of the gifts sent by Jacob to Joseph. There can

be little doubt that the lot of the Hebrews is the λάδανον of the Greeks and the

ladanum of the moderns. It is a resin yielded by a species of Cistus (C.

villosus) found in Palestine, Cyprus, and other parts of the Mediterranean area.

It was formerly much esteemed, but is now scarcely used, except by the Turks,

who value it as a perfume and a fumigator. The plant was not introduced into

Egypt until a much later date; hence the consistency of the gift as an offering

to the Egyptian ruler. NARD, SPIKENARD (Heb. נֵרְדְ, Gk. νάρδος).

Probably this compound, the gift of the sister of the wealthy Lazarus of Bethany to her Teacher and Lord, was among the most valuable of the many costly unguents procured by ancient nations from the East. Judas valued the quantity thus expended at some nine or ten pounds sterling, and among various corroborative instances may be quoted that of the poet Horace, who offers his friend Virgil a cadus (say thirty-six quarts) of wine for a small onyx box of spikenard6 Dioscorides mentions seven ingredients, including myrrh and balm, and of course oil, as composing the 'ointment.' The NARD or 'nardus' from which this perfume was named is the produce of an Indian plant, of the tribe which furnishes our garden valerian, and grows at Nepaul and Bhootan at great elevations. It is small and herbaceous, and has been compared to 'the tail of an ermine' from its downy branches and leaves. and the fibrous covering of the roots. It is in the latter that the odoriferous property resides. Like our own valerian, Nard is and was prized as a medicine as well as a perfume. Botanists have given it the name of Nardostachys jatamansi, the latter being its Hindoo name, while the former is equivalent to spica nardi or spikenard, probably so called because the plant had 'many spikes from one root.' The smell which it exhales would not be deemed altogether agreeable from a Western standpoint, but evidently the standard was different in the East, and even in Southern Europe, in former times. 'While the king sitteth at his table, my spikenard sendeth forth the smell thereof' (Song of Solomon i. 12). The alabastron of ointment brought into Simon's house by the repentant sinner as a gift to Christ, was probably a valuable compound similar to that subsequently offered by Mary of Bethany. No doubt the Indian nard was conveyed to Italy through Phoenicia, as the identity of the Hebrew (or rather Persian) and Greek names suggests. We thus find Horace, in one of his more convivial odes, inviting his friend to drink with him, 'perfuming' their ' grey hairs ' with roses and 'anointing ' themselves ' with Assyrian nard7." Syrian nard ' is also spoken of by Tibullus. There are no other specific references to spikenard in the Bible than those already cited, together with Song of Solomon iv. 13. SAFFRON (Heb. כַּרְכּׂם karkom).

This now comparatively neglected plant was known in the East in remote ages, and brought to Europe as an exotic of value, though difficult to rear. It has been known in England for several centuries, and was grown round Saffron Walden and in other localities. One smoke-pervaded spot in the heart of London still bears the name of 'Saffron Hill.' It is a somewhat expensive product, the economic value residing in the stigmas of the flower, 60,000 of which are needed to make one pound of saffron. It is now chiefly imported for its bright yellow dye, though occasionally employed also in medicine but on the Continent and in the East it is still an ingredient in cookery. Both in Asia and Europe, however, its reputation has much declined, since the Arabs introduced its cultivation into Spain as an article of commerce, and bequeathed to us the modern title of zaffer or SAFFRON. A much older name is that which the Saffron Crocus (C. sativus) and its allies bear in our gardens;—the crocus of the Romans is the κρόκος of the Greeks, and the karkom of the Semites, through whom European nations first became acquainted with the plant. We have no means of judging what amount of importance was attached to it by the Jews, as it is only named once in Scripture, as above quoted, among the odoriferous plants in the gardens of Solomon. But to the nations of Eastern Asia, its yellow dye was the perfection of beauty, and its odour a perfect ambrosia. Saffron yellow shoes formed part of the dress of the Persian kings,' says Professor Hehn, 'which was copied from the older Babylonio-Median costume.' Greek myths and poetry exhibit to us an extravagant admiration of the colour and the perfume. Homer sings 'the saffron morn;' gods and goddesses, heroes and nymphs and vestals, are clothed in robes of saffron hue, and fair maidens are called 'saffron-haired,' where we should say 'golden-tressed.' Large quantities were imported into Italy from the East; and the saffron of Lydia, Cilicia, and Cyrene was specially prized. The scent was valued as much as the dye; saffron water was sprinkled on the benches of the theatres, the floors of banqueting halls were strewn with crocus leaves, and cushions were stuffed with the same material. But the glory has de-parted from the fair and fragrant flower as from the lands wherein its praises were sung. Nor need we indulge in sentimental regrets; the course of pagan faith and culture was a downward progress, and blighted some of the fairest gifts of heaven: 'The trail of the serpent was over them all;' and tree and shrub and flower were degraded into auxiliaries of sensual indulgence and riotous prodigality. A purer faith has wrought out a nobler civilization, and restored to them, at least in some degree; their first and higher ministry, as messengers of God to man.

|

|

|

|

|

1) Odyssey, lib. iv. 2) It has been suggested that the 'ivory palaces' of Psalm xlv. 8, and the ' tablets' (R. V. 'perfume-boxes') of Isaiah iii. 20 alike denote these caskets. 3) So Virgil, Georg. lib. ii. 118, 'odorato sudantia ligno Balsama.' 4) Antiq. lib. iii. ch. 7, § 6, 5) Georg. lib. iii. 415; see also iv. 264. 6) Carm. lib. iv. od. 12. 7) Carm. lib. ii. od. 11.

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD

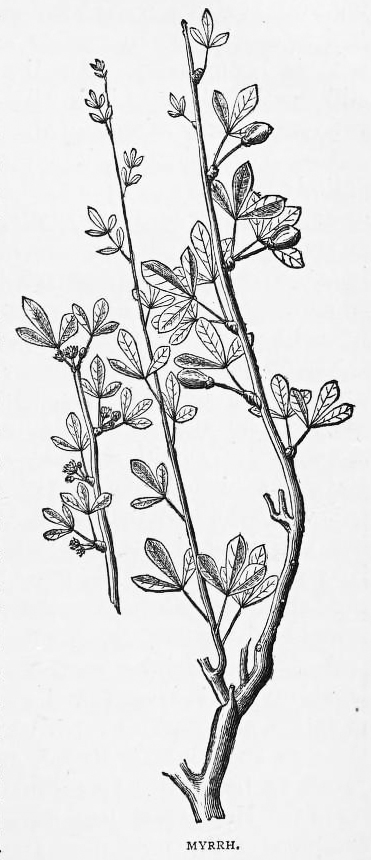

This, one of the most familiar of aromatic products in both ancient and modern

times, requires no identification, the name and the substance having been handed

down through the ages. As already stated, it is the gum of a species of

Balsamodendron, the genus producing the fragrant Balm, and perhaps also the

Bdellium, of the Old Testament. MYRRH is yielded—whether by the recognized

species only (B. myrrha) or not, cannot positively be stated —in both Arabia and

India; that of commerce is usually imported from Bombay. It has also been met

with in Abyssinia. The gum exudes from wounds made in the bark, and appears as

lumps of irregular size and shape, of a reddish brown colour, and having an

aromatic smell and bitter taste. The tree is low and scrubby, the branches

stiff, stout, and spinous, the leaves triple, and the fruit a small 'plum.' It

is found growing in Arabia among different kinds of Euphorbias and Acacias.

This, one of the most familiar of aromatic products in both ancient and modern

times, requires no identification, the name and the substance having been handed

down through the ages. As already stated, it is the gum of a species of

Balsamodendron, the genus producing the fragrant Balm, and perhaps also the

Bdellium, of the Old Testament. MYRRH is yielded—whether by the recognized

species only (B. myrrha) or not, cannot positively be stated —in both Arabia and

India; that of commerce is usually imported from Bombay. It has also been met

with in Abyssinia. The gum exudes from wounds made in the bark, and appears as

lumps of irregular size and shape, of a reddish brown colour, and having an

aromatic smell and bitter taste. The tree is low and scrubby, the branches

stiff, stout, and spinous, the leaves triple, and the fruit a small 'plum.' It

is found growing in Arabia among different kinds of Euphorbias and Acacias.