By-Paths of Bible Knowledge

Book 10 - The Trees and Plants Mentioned in the Bible

Henry Chichester Hart, B.A. (T.C.D.), F.L.S.

Chapter 1

|

SKETCH OF THE VEGETATION OF PALESTINE AND THE NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES.

The interest surrounding that limited portion of Western Asia which modern writers agree to call by its classical name of Palestine, is wholly unparalleled both in nature and degree. The love of the Swiss for their native mountains, or the Scotsman's attachment to the 'land of brown heath and shaggy wood,' affords but a faint type of that glowing and reverent affection with which Christians of every race and nation have constantly regarded their more than Fatherland — the birthplace of their faith and hope. The devotion which once drew pilgrims to its venerable metropolis, — to them the geographical centre of the globe, — established hermits amidst its rocky solitudes, and inspired the grand but reckless fanaticism of Crusaders, finds its modern counterpart in a growing and intelligent interest in all that concerns the Holy Land, its history and topography, its past and present inhabitants, and its vegetable and animal productions. Science has taken the place of superstition; and without the loss of true reverence, sacred sites, long encircled with the delusive halo of legend and romance, are measured and mapped out by the careful hand of the surveyor. To gain and to preserve a faithful transcript of the material proportions and natural peculiarities of the country; to trace the course of its once-frequented highways, explore its silent wastes, and disinter from shapeless mounds the scanty and broken relics of former industry and civilization; to enumerate and identify the trees and shrubs which still clothe the hill-sides, the flowers which emblazon the vernal soil, the cattle yet roaming on the upland pastures, and the birds which 'sing,' as of old, 'among the branches'; — all this and much more it has been reserved for our own age to attempt, and in large measure to accomplish, in Israel's ancient heritage: a crusade well worthy of the intelligence, and not less worthy of the piety, of the nineteenth century. Every student of Holy Scripture will naturally seek to form mental conceptions of the scenes amidst which its several portions were written, and the chief events which it records were enacted; from which, also, its varied and impressive imagery was derived. And to do this with even approximate accuracy demands some acquaintance with the general features of Oriental vegetation. It is true that what Von Humboldt aptly termed the 'physiognomy 'of any country is based primarily on its geological structure, the character and arrangement of its rock-masses; but the clothing of its stony skeleton, its numberless modifications of external form and colour, are due chiefly to its vegetable life. More than skies or clouds, more than valleys or hills, more than sentient creatures of high or low degree, the trees, shrubs, and flowers of a land give character to its scenery; impressing the mind by their grandeur, or charming it by their beauty. In a previous volume of the present series1 the geological peculiarities of Palestine and the countries which border [it have been ably and adequately described. The reader will thus have been made acquainted with those remarkable diversities of elevation by which a territory so small as that of the Hebrews should yet include within itself a climate so strangely varied. If Palestine had been a plain, its climate would have been comprised in the sub-tropical zone extending from lat. 33½° to 34°; but, owing to the inequalities of its surface, no less than five out of the eight zones recognized by geographers are represented within its limited area. On the snow-capped peaks of Lebanon the climate approaches an Arctic severity, while the lower parts of the Ghor, or Jordan valley, experience a tropical heat. Between these extremes of temperature we have the climates of the western coast, the inland plains and lower hills, the higher uplands, and the loftier table-lands beyond Jordan. Out of this strangely-varied climate springs a corresponding complexity in the animal and vegetable life of the country; and the English traveller is struck with the sight of familiar forms, mingled with exotics which remind him how far he has wandered from the temperate fauna and flora of Northern Europe. Tropical bats, Indian owls, and Ethiopian sun-birds are to be found within the borders of the Holy Land, no less than the robins and skylarks, finches and wrens of colder latitudes. The paper-reeds of Egypt and the palms and acacias of the desert are represented, equally with the oaks, willows, and junipers of Europe. The general aspects of the vegetation of Palestine may be briefly summed up as follows: — The plants common to the plain of the coast and the southern highlands are for the most part identical with those found in the other countries bordering the Mediterranean east of the Straits of Gibraltar. Here grow the Aleppo pine, the myrtle and ilex, the grey olive and the green arbutus, the carob or locust tree, the orange and citron; the vine, the fig-tree, and the pomegranate. The bay and the oleaster flourish "on the hills, and the streams are overhung by the roseate blossoms of the oleander. The rest of the table-lands which constitute the greater part of Palestine, both east and west of the Jordan, include a flora of a more widely diffused character, comprising plants of Central Europe and Western Asia, with not a few species growing in our own island. Among them may be mentioned pines and junipers, the terebinth, the almond, apricot and peach, the hawthorn and mountain ash, the ivy and honeysuckle, the walnut and mulberry; oaks, poplars, and willows; the majestic cedars of Lebanon, the melancholy cypress, and the plane-tree with its wide-spreading shade. The vegetation of the Jordan Valley, on the other hand, is of a type most closely allied to that of Northern Africa, with a proportion of Indian, as well as of European, species. Here the date-palm once flourished, though only a few stragglers now remain; here grow the acacia and the retem of the desert (the 'shittim 'and 'juniper'of Scripture), and many less-known plants, represented in Africa but not on the European continent. In point of climatal conditions, Palestine is most favourably situated. 'The inhabitants,'says Meyen, 'rejoice in the happiest clime. The warmth of the summer enables tropical plants to grow on the plains; thus, the date-palm and the fig (the edible species and the sycomore-fig) found a home in Southern Syria, in sheltered spots. The strip of coast tended to diminish the extremes of temperature, and thus palms grew, and still grow, in the maritime plain. Palestine was also able to boast a large number of more northern plants, belonging strictly to the warmer temperate zone, on the edge of which Northern Palestine is situated. Hence it gained many beautiful evergreen trees and shrubs, myrtles, laurels, cistuses, and other important plants of Southern Europe, not to speak of the vine and pomegranate2.'Humboldt, in his Aspects of Nature, enumerates sixteen3 tribes of plants, whose forms determine natural scenery — so far, of course, as its botanical element is concerned. Of these, fully half are represented in Palestine, viz. the palms, acacias, laurels, myrtles, pines, willows, mallows, and lilies. From a country thus rich in diversities of climate, elevation, and natural productions, the sacred writers were led to draw their supplies of imagery in the composition of a world-wide volume. This fact has been often dwelt upon; but it has not so frequently been remarked that the resources of the Greek and Latin poets were not dissimilar in kind, though inferior in variety, so far as related to the vegetable forms by which they were surrounded. Hence there is considerable resemblance between the 'botany of the Classics 'and the 'botany of the Bible4.' A country of woods and forests, in the sense in which that might have been affirmed of Great Britain ten centuries ago, Palestine is not now, nor does it seem to have been such within the historic period. Its hill-tops were covered with a soil too thin to encourage the growth of large timber-trees. We thus find frequent reference in Scripture to single trees (chiefly in the south) as familiar landmarks, which could hardly occur in a woodland district. Still, there are woods and forests in Western Palestine, and more extensive ones on the table-lands east of the Jordan; and there is every reason for concluding that there was a much larger area so occupied in former days than now. 'As soon,' remarks Professor Schouw, 'as a race rises to agriculture, it becomes hostile to the forests. The trees are in the way of the spade and plough, and the wood gives less booty than the field, the garden, or the vineyard. The forest, therefore, falls beneath the axe. . . . And thus, under like circumstances, the country in which civilization is oldest possesses the fewest woods. Hence forests are more sparingly met with in the countries of the Mediterranean than northward of the Alps. 'It seems probable, therefore, that the clearing process had begun in Palestine long before the Hebrews settled there, and that it has continued to a varying extent since their dispersion. Mr. Consul Finn5 has wisely pointed out the need of caution in drawing general conclusions respecting even the present amount of woodland in Western Palestine, seeing that very much is inaccessible to travellers who pursue only the normal routes in visiting the country. He also comments on the wholesale destruction of growing timber in the neighbourhood of towns and villages for the purposes of fuel, which goes on with characteristic disregard of consequences by the peasantry, and with equally characteristic indifference on the part of the government. There is evidence that the now comparatively bare hills of Judah and Benjamin were diversified by oak-woods at quite a recent period. Nor must the effects on vegetation of the successive and devastating invasions to which Palestine has been subjected be overlooked in our estimate. The proud boast of the Assyrian monarch that the cedars and fir-trees of Lebanon and the woods of Carmel should fall before the axes of his soldiery is but a sample of the relentless destructiveness of ancient pagan warfare. The Mosaic law mercifully prohibited the felling of any fruit-bearing tree even in an enemy's territory; but both the Egyptians and the Assyrians cut down fruit and timber-trees indiscriminately, as the monumental inscriptions and bas-reliefs amply testify. From Sennacherib to Titus, the enemies of Israel smote the choicest vegetation of the land; and we are reminded by the pathetic words of the latest Jewish historian, how, in the neighbourhood of the doomed city, the trees were everywhere felled for the military engines of the besiegers, and how wood failed to supply crosses in sufficient abundance on which the wretched inhabitants might be nailed in hideous mockery by the Roman legionaries6. In the far north, two extensive forest regions remain; that known as the Belad Besharah in Upper Galilee, between the Jordan and the warm Phoenician plain; and, south of the former, a district extending from near Caesarea to the plain of Buttauf above Acre. This, the ingens sylva of Roman writers, adjoins the Carmel ridge, and their united thickets of oak constitute the 'forest of Carmel 'just mentioned. The aspect of the two ranges of Libanus and AntiLibanus is at first bare and rugged, as their geological structure would lead us to anticipate; but beneath these mighty crags of reddish yellow, glowing beneath a sky of intensest blue, lies an oasis of almost unequalled beauty and fruitfulness. Nestling in these secure retreats — the 'rocks' of their 'strength' — dwell Druse and Maronite, a hardy and industrious race, turning to account the splendid natural advantages of their mountain home, and rendering it, in the words of Lamartine, 'an Eden restored.' The slopes are terraced for grain and a variety of fruit-trees; villages lie embosomed in ruddy orchards and groves of mulberry, — the characteristic tree of Lebanon. Oranges, peaches, apricots, plums, cherries and almonds, thrive at different elevations, according to their several ranges of temperature. Here, as almost everywhere else in Palestine, the vine and pomegranate yield their rich produce. In the warmer and more sheltered spots the palm and the olive, the fig and the walnut, find a congenial home; green oaks abound higher up the mountain side, and higher still, the pine, cypress, and juniper crown the successive zones of vegetation with their sombre foliage. On Lebanon, such Northern species as the mountain ash, the box, and the berberry have found a refuge; while humbler plants, like the wild rose, geranium, and honeysuckle, impart an almost English aspect to the scene. And beside the many 'streams from Lebanon,' willows and poplars, the Oriental plane, and the crimson oleander, with a mass of lowlier vegetation, flourish as in Bible days. In the lofty table-lands beyond Jordan — the southward extension of Anti-Libanus — pine forests clothe the summits of the highest hills; lower down, woods of evergreen-oak adorn the park-like scenery of ancient Gilead and Bashan; and, mingled with them, the rich foliage of the myrtle, the arbutus, and the carob or locust-tree, varied with the pink and white blossoms of the retem bush. 'The traveller who only knows Palestine to the west of the Jordan,' says Mr. Laurence Oliphant, 1 can form no idea of the luxuriance of the hill-sides of Gilead, doubly enjoyable by the contrast which they present to the rocky, barren slopes of Galilee and Judea. Here we crossed sparkling rivulets, where the sunlight glinted through the foliage. . . and brakes and glades, seldom disturbed by the foot of man. In places the forest opened, and the scenery resembled that of an English park, the large trees standing singly on the long grass; while at others, where possibly in old days there had been well-cultivated farms, the trees gave way altogether to luxuriant herbage, encircling it as though it were a lake of grass into which their long branches drooped7.' The country further to the south, formerly known as the territories of Ammon and Moab, is more sparsely wooded, the terebinth being the predominant tree; but it is equally rich in pastures, as Scripture would lead us to suppose. In Galilee, besides the oak woods already mentioned, a dense undergrowth of mastic, hawthorn, and spurge-laurel overspreads the hills; there and elsewhere replacing the ancient woods. Thistles and thorny plants abound, with flowers of every hue in the early springtime. The terebinth is not uncommon, and the vine is extensively cultivated, as in the Lebanon district further to the north. In the plain of the Buttauf in Lower Galilee, corn, cotton, and almost every species of vegetable grow luxuriantly. Nazareth, a few miles distant, nestling amidst a circlet of some fifteen hills, 'like a rose set round with leaves/ has still its palms and cypresses, its fig-trees and gardens. Crossing the memorable plain of Esdraelon, the 'battle-field of Palestine' and one of its richest fields of cultivation, we pass into the fertile and well-watered district of Samaria. Captain Conder thus graphically describes the Vale of Shechem, the most luxuriant in the whole land: — 'Long rivulets, fed by no less than eighty springs (according to the natives), run down the hill-slopes and murmur in the deep ravines; gardens surround the city walls; figs, walnuts,, mulberries, oranges, lemons, olives, pomegranates, vines, plums, and every species of vegetable grow in abundance, and the green foliage and sparkling streams refresh the eye. But as at Damascus, the oasis is set in a desert, and the stony barren mountains contrast strongly with the green orchards below8.'The hills of Samaria appear to be most favourable for the growth of the olive, and indeed this most characteristic tree of modern Palestine abounds both on the higher and lower grounds, overspreading the former and growing amidst the gardens planted in the valleys. Mr. Buckingham remarks that, 'while in Judea the hills are mostly as bare as the imagination could paint them, and a few of the narrow valleys only are fertile; in Samaria, the very summits of the eminences are as well clothed as the sides of them. These, with the luxuriant valleys which they enclose, present scenes of unbroken verdure in almost every point of view, which are delightfully varied by the picturesque forms of the hills and vales themselves, enriched by the occasional sight of wood and water, in clusters of olive and other trees, and rills and torrents running among them.' The difference between these two adjacent districts has been often commented on, not always without exaggeration. But the tame, bare, and desolate aspect of so much of the southern highlands of Palestine, including the environs of Jerusalem, is mainly due to the two causes already adverted to: the destruction of timber — resulting here, as in some parts of France and Italy, in the sweeping away of a once productive soil; and the neglect of the ancient terrace-cultivation. Speaking of the neighbourhood of Bethlehem, Canon Tristram remarks, that 'the hill-sides are clad with dwarf oak, bay, lentisk, and broom.' The sides of the glen where once were the famed Gardens of Solomon, are 'steep, rocky, and torn.' Yet Bethlehem, tenanted by a Christian population, has its oliveyards and vineyards as of old, and the portion of the Gardens now cultivated sends abundance of peaches, apricots, figs, almonds, and pomegranates to the markets of Jerusalem. A like observation applies to the district still further south. A walk up the Vale of Eshcol, once renowned for its vines, 'revealed to us,' says the writer just quoted, 'what Judah was everywhere else in the days of its prosperity. Bare and stony as are the hill-sides, not an inch of space is lost. Terraces, where the ground is not too rocky, support the soil; ancient vineyards cling to the lower slopes; olive, mulberry, almond, fig, and pomegranate trees fill every available cranny to the very crest; while the bottom of the valley is carefully tilled for cress, carrots, and cauliflowers, which will soon give place to melons and cucumbers. That catacomb of perished cities, the " hill country of Judah," is all explained by a walk up the Vale of Eshcol9.' The aspects of these Judean hills, as their geological structure would suggest, is not unlike that of our chalk downs, with their rounded summits and scant herbage; but, like them, not destitute of timber in favourable spots. The route southward from Hebron passes over plains of arable land lying between hills clothed with evergreen-oak and arbutus, with pine-trees on the eminences. Here, as elsewhere round the capital, the destruction of trees and shrubs for charcoal-making goes on at an increasing rate. The district of the Negeb or 'South Country,' into which the hills of Judah gradually melt, is of similar external character. Low hills and rolling downs, carpeted with grass and adorned in early spring with countless flowers, meet the eye of the traveller who ascends into the 'South' from the desert beyond; or, like Abram, 'goes down' from Hebron or Mamre on his way to Egypt. Scarcely any trees are to be found here, except an occasional tamarisk. Springs are infrequent; but tribes of Bedouin nomads find abundant pasturage for their flocks in the territories of the ancient Amalekites. These natural terraces formed the southern border of Israel's inheritance.

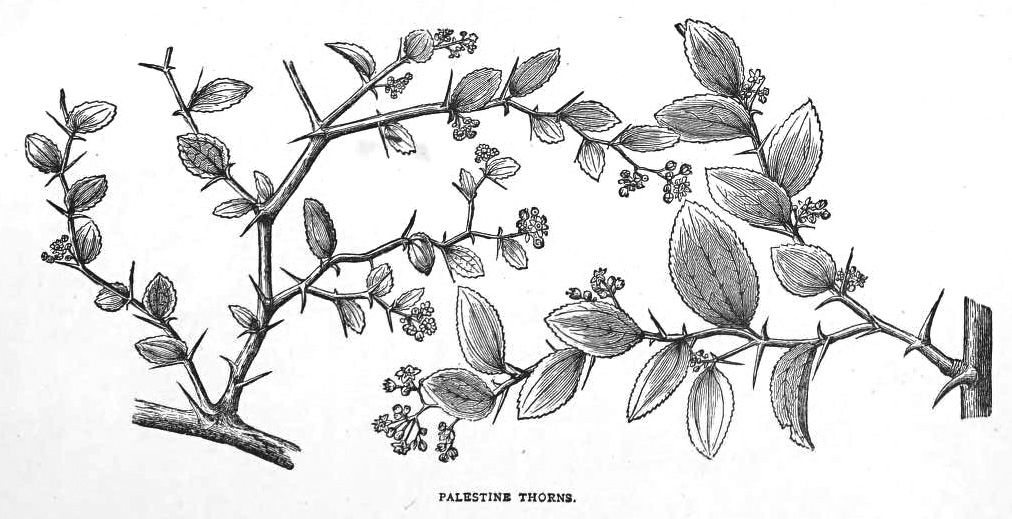

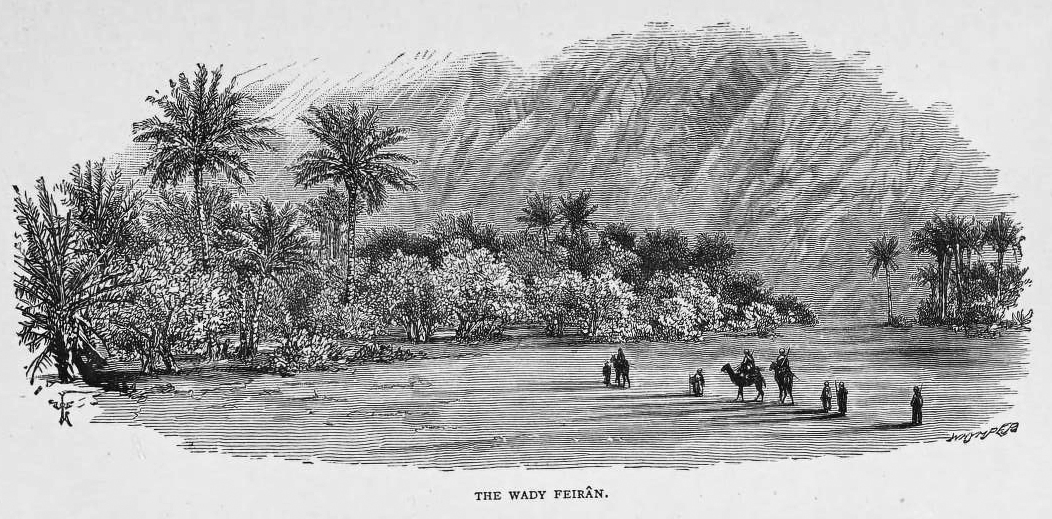

The Valley of the Jordan possesses, as already intimated, a flora of its own. The swift-flowing river burrows more and more deeply into its rocky bed throughout its winding course of nearly two hundred miles, from the foot of Hermon to the Dead Sea. The vegetation of the upper part, above the Lake of Galilee, affords a strange mixture of Northern and Southern forms. 'Luxuriant willows,' says Mr. Lowne, 'fringe the stream, whilst dense thickets of tamarisk, buckthorn, Spina Christi thorn, and plane-trees shut out the view for miles, and shelter a tangle of wild roses, brambles, and vines.' Mr. John Macgregor, whose canoe was probably the first boat that ever navigated the upper part of the river, speaks of the eastern source, near Banias, as being in a grassy and well- wooded region. The spring is surrounded by a thorny and impenetrable thicket, below which the water bursts forth under 'a mass of fig-trees, reeds, and strongest creepers.' He adds, 'A splendid terebinth and a not less splendid oak droop over the infant stream10.' The northern portion of. Lake Hûleh — the Biblical 'Waters of Merom' — is covered by an immense tract of floating thickets of papyrus; and white and yellow water-lilies adorn the more open portions. Thence the river rushes down, 'between rocks thick-set with oleanders.' As it emerges and prepares to enter the Galilean Lake it spreads into a sort of grassy delta, fertile and dotted with trees and bushes. A few palm-trees grow near the lake at this end, and others occur at different points, not far from the shores, on both sides. Josephus alludes to these, and to the fact that walnuts, figs, and olives flourish in this delightful district11. Oleanders fringe the sandy beach at Gennesareth, and the grass is gay with flowers of every hue, in their brief bright springtime. On quitting the Sea of Galilee the downward stream pursues its winding course through a valley of varying breadth. This valley, the Gkôr ('hollow') of the Arabs, is the Arabah of the Old Testament, usually rendered 'plain,' but left untranslated in Josh, xviii. 18, &c. It presents in some parts two, in others three, levels or terraces on either side of the river. The course of the Jordan is everywhere marked by a thick jungle of reeds, tamarisks, and oleanders, with islands, here and there, similarly overgrown. Circles of verdure indicate the presence of springs or the debouching of tributary streams from wild and wooded gorges into the main current. Canon Tristram thus describes the winding course of the river between its terraces, as seen from the heights above: — 'First, gradually declining from the western hills, and formed principally of their debris,, is the upper terrace, on which stand the two great oases of Ain Duk and Ain Sultan, commencing at a height of 750 feet above the level of the Dead Sea, and sinking at Er Riha [near the site of Jericho] to 500 feet. Hence a somewhat steep slope descends nearly 200 feet to the second plateau. This is now barren, but merely so from neglect, except in the portion nearest the lake, where the soil is impregnated with salt, and covered with efflorescence of sulphur. Thirdly, comes the extent of ground about 100 feet lower still, occasionally overflowed by the river; and, lastly, fringing the stream and very frequently under water, the narrow depressed belt, which is a mere tangle of trees and cane, often only a few yards in width.' Here the date-palm formerly attained its greatest luxuriance. The celebrated palm-grove which gave to Jericho its ancient title (Deut. xxxiv. 3) is said to have been eight miles in length by three miles broad. Of the district Josephus wrote: 'There are in it many sorts of palm-trees,. . . different from each other in taste and name; the better sort of them, when pressed, yield an excellent kind of honey. . . . The country withal produces honey from bees; it also bears that balsam which is the most precious of all the fruits of that place; cypress-trees also, and those12 that bear myrobalanum. . . . And indeed, if we speak of these other fruits, it will not be easy to light on any climate on the habitable earth that can well be compared with it.' With the exception of a few specimens growing near the houses of modern Jericho, no representatives of the palm-forest remain in the neighbourhood. Yet their relics are not difficult to discover in the vast assemblage of tree-trunks which lie heaped at the northern extremity of the Dead Sea, and the half-fossilized palm-leaves to be found in recently-formed limestone at Ain Jidy, the ancient Engedi. Of the valleys which open towards the Jordan on its western side, two have perennial streams, the Jalud and the Farah. The latter runs rapidly through a delightful vale, and is fringed with reeds, oleanders, and aromatic herbs. On the eastern side of the Ghôr are three important rivers, the Yarmuk, the Zerka or Jabbok, and the Modjib or Arnon. There is also the Zerka M'ain, a brook east of the Dead Sea. The gorges through which these streams descend are clothed with the most luxuriant vegetation. Enormous oleanders with their crimson blossoms, and the beautiful white retem, with terebinths, oaks, and arbutus, make up some of the most picturesque scenery in the land of Israel; while here and there palm-trees rear their graceful crests, and cornfields spread out on the plain below. One other district claims a brief notice. The Maritime Plain and adjacent hills of the Shephelah, or 'low country,' lying between the Mediterranean and the highlands of Western Palestine, enjoy a climate eminently favourable to vegetation. Warm and sheltered, the palm and tamarisk of the Desert and the Arabah flourish abundantly, with the fig and terebinth, and of course the ubiquitous olive, vine, and pomegranate; oaks, evergreen and deciduous, grow on the slopes, pines on the hill-tops, and abundance of small shrubs and flowers beneath. Waving fields of wheat and barley remind us of the days when Philistia was the granary of Canaan; and the sycomore-fig, too tender for the highlands above, grows abundantly in the 'vale,' as of old, and along the coast. The sites of human settlements, ancient and modern, — Gaza, Jaffa, Ramleh, as well as Acre and Caiffa further north, — are embosomed in orchards and gardens; and the streams which run westward to the Mediterranean are bordered with canebrakes and adorned with oleanders and willows; in some cases, also, with the slender paper-reeds of Egypt. Thus, wherever the observant traveller turns his steps within the limits of Israel's former inheritance, he finds a climate and a soil of striking and almost unequalled capabilities, regarded in relation to its very limited area. Yet it is not less obvious that for the full realization of those capabilities, there is needed the aid of constant and persevering industry on the part of its inhabitants. And that this was the case from the earliest times seems evident from such descriptions as that in Deut. viii. 7-9, where the productions enumerated are those which derive their value from cultivation. It was wisely and beneficently ordained that the natural resources of Palestine should require the healthful exercise of human effort for their full development; and this is still observable in its present degenerate condition, both by what has been lost and by what still remains of scenery and vegetation. A picture of Western Palestine would lose its most pleasing features if the cultivated trees and shrubs were absent. Throughout the country, from Lebanon to Southern Judea, the olive, the fig, the vine, and the pomegranate, are cultivated in favourable situations, as circumstances permit; though in greatly diminished numbers as compared with Biblical times, when the bare limestone hills, now dotted only with olives almost as grey as themselves, were tapestried with vines rising in terraced festoons, one above another, so abundant and so fruitful as to be a favourite type of the Israelite nation13. The pistachia tree and the black and white mulberry are also generally cultivated, and sufficient crops of wheat and barley are still raised to form part of the exports of the country. In what are our winter months, the meadows and pastures are ablaze with flowers of every hue, — ranunculuses, aromatic herbs, and bulbous plants being conspicuous, — but their glory is short-lived; as the solar heat increases, 'the grass withereth, the flower fadeth,' and the spring blossoms are £ cast into the oven,' for fuel, as of old. Wherever warmth, sheltered position, and moisture prevail, the fertility of the soil speedily becomes apparent. These conditions are attained in the plains which traverse the highlands or border the coast, and in the innumerable valleys which wind among the hills. Besides the twelve important streams which run into the Mediterranean and the Jordan valley respectively, the uplands are intersected by wadys, or torrent-beds, which in the rainy seasons form channels for countless brooks. The junction of the limestone strata with the superjacent chalk also gives rise to numerous springs, from which the names of so many Scripture localities derive their prefix Ain or En. And even where these superficial supplies are wanting, the well and the cistern formerly yielded all that was required, except in seasons of drought; and might easily be made to do so again. Thus, dowered by nature and enriched by human industry, Palestine was emphatically 1 a good land, a land of brooks of water, of fountains and depths that spring out of valleys and hills;' a land whose inhabitants could 'eat bread without scarceness,' and 'not lack anything in it.' It was 'a pleasant portion' and 'a delightsome land' (Deut. viii.7-9; Jer.xii.10; Mai. iii. 12). But centuries of misrule and neglect have combined with natural agencies to make desolate this once favoured heritage. The winter rains have swept the thin soil from the hill-sides, the sword of the conqueror and the axe of the peasant have demolished both forest and fruit-tree; many a spring has thus run dry, and many a stream now feeds only a pestilential marsh; the soil 'mourneth and languisheth,' and the ancient prediction is fulfilled by the operation of natural but unerring laws. 'Lebanon is ashamed and hewn down; Sharon is like a wilderness; and Bashan and Carmel shake off their fruits '(Isaiah xxxiii. 9). Nor with less complete and literal accuracy does the modern botanist confirm the prophetic denunciation — 'Upon the land of My people shall come up thorns and briers; yea, upon all the houses of joy in the joyous city;' 'The thorn and the thistle shall come up on their altars '(Isaiah xxxii. 13; Hosea x. 8). With the exception of North-western Arabia and the valley of the Nile, the vegetable productions of the countries surrounding Palestine hold but a slight relationship with 'the Botany of the Bible.' The flora of Northern Syria does not differ materially from that of Palestine. The wide plains which stretch far away beyond the table-lands east of Jordan are seldom referred to by the sacred writers, while the plants of the countries still further east, like those of the scenes of apostolic travel, supply but a few references, either in the Old or New Testament. The vegetation of the peninsula of Sinai, however, and that of Egypt, cannot fail to be of interest to Bible readers. The phrase 'general vegetation 'is somewhat of a misnomer as applied to the former territory; the presence of plants which give character to a landscape being the exception, and not the rule. The air, though pure and exhilarating, is extremely dry; and the rainfall being very limited, springs and streams are rare, except in certain localities, such as the granite district round Mount Sinai. But wherever moisture is found, oases occur green with pastures, and glens and wadies, where the maidenhair-fern overhangs the sheltered pools with its fairy fronds, and lavender, mint, and thyme exhale their fragrance amidst the mosses and sedges by the water-side. The characteristic trees of the peninsula are the date-palm, the acacia, and the tamarisk. Beside these there are the wild fig and wild palm, a willow, the carob or locust-tree, and the retem or white broom; beside the fruit-trees common in Palestine, but these, for the most part, have probably been introduced into the peninsula by human agency. Of the above, the acacia and tamarisk are the most frequent. Palms abound in the oases; the caper and other small plants spring here and there out of rock crevices; but neither trees, shrubs, nor flowers are sufficiently numerous to affect the general features of this 'dry and thirsty land.' The hardy camel contrives to extract satisfaction and nourishment from the dryest and most prickly growths of the wilderness; but the zoology and botany of this territory are alike of the most limited character. 'In lighting upon a tree or a well you seem to be meeting with a friend. It is an event which deserves record.' Dr. Bonar (just quoted) describes, in a few forcible sentences, the essential diversity of the aspects of vegetation in Sinai and Palestine. Speaking, of the Wady Feiran (generally, but as he thinks incorrectly, identified with Rephidim), the Doctor remarks: 'The whole valley is well watered, as its verdure shows; not the verdure of grass, as with us (you do not see that in the desert, save round a well or a rill), scantily either in Egypt or Palestine, nor the verdure of forest trees;. . . but the verdure of palms and tamarisks, such vegetation as is sufficient to feed the Arab and his camel.' He adds: 'I did not see anything in the desert that I could call even a thin clothing of vegetation; even where the shrubs abound in the wadys there is no show of what we should call "green." Vegetation is so dull in its hue that it does not look like verdure14.'

The reader will, however, have observed that the scanty flora of the desert, so far as it extends, corresponds in a considerable degree with that of the Lower Jordan valley, and particularly of the district adjoining the Dead Sea15). The indigenous flora of Egypt, the Egypt of the Bible, differs but little from that of the Sinaitic peninsula and the Lower Ghôr. The cultivated plants, however, were very numerous, if we may judge from the list given by Pliny, illustrating the high civilization which so long prevailed in the valley of the Nile. But there is no variety in the vegetation, the physical structure of the country — an alluvial plain of very varying width, bordered by two ranges of limestone hills — rendering it a striking contrast to Palestine. 'For the land, whither thou goest in to possess it, is not as the land of Egypt,. . . where thou sowedst thy seed, and wateredst it with thy foot, as a garden of herbs: but. . . is a land of hills and valleys, and drinketh water of the rain of heaven' (Deut. xi. 10, n). Dean Stanley has graphically pictured, in a few words, the aspect of this 'oasis of the primitive world': 'Immediately above the brown and blue waters of the broad, calm, lake-like river, rises a thick black bank of clod or mud, mostly in terraces. Green — unutterably green — mostly at the top of these banks, though sometimes creeping down to the water's edge, lies the Land of Egypt. Green — unbroken, save by the mud villages, which here and there lie in the midst of the verdure, like the marks of a soiled foot on a rich carpet; or by the dyke, and channels which convey the life-giving waters through the thirsty land16.'It is as difficult to conceive of this narrow strip of verdant soil as the garden and granary of the ancient world, as to think of 'the basest of kingdoms 'as having once swayed the destinies of our race; to the Hebrew patriarchs an asylum in famine, to their children 'a house of bitter 'bondage,' to their later descendants a perilous and deceitful ally. But here^ as in Palestine, the changed 'aspects of nature 5 are due, not to earth or sky or air, but to the influence of man. In the opinion of Sir Gardner Wilkinson, 'Egypt, if well cultivated, could now maintain many more inhabitants than at any former period, owing to the increased extent of the irrigated land.' Fewer timber-trees are now reared in Egypt than formerly, as in Palestine, and for a like reason; the ancient inhabitants delighting in horticulture, and importing exotic trees, shrubs, and flowers, to adorn their groves and gardens. Most of the native plants are still represented, though in diminished numbers. But while the papyrus has disappeared from Lower Egypt the date-palm, there is some reason for thinking, is now cultivated to a greater extent than formerly. In and around the towns and villages it forms the most conspicuous and the most graceful object. Groves of palm, acacia, and tamarisk were, and still are, among the natural beauties of the Nile valley, and the sycomore-fig was once abundant there as in Palestine. The doum-palm with its branched stem and fan-like leaves is very common in Upper Egypt, adorning the fields and shading the sun-burnt soil; and in some places forming 'little woods which enchant the sight.' The acacia, also, c grows commonly on the parched and barren plains 'which are so numerous in the Thebaid. The vine, fig, olive, and pomegranate were diligently cultivated by the ancient inhabitants, together with a profusion of vegetables, melons and pumpkins among the chief, such as tempted the c desert-wearied tribes 'to return to the land of their captivity. Of the 'corn in Egypt' no Bible reader needs to be reminded, wheat and barley being grown in every part of the country; and large crops of flax, lentils, peas, and beans were raised without difficulty from the rich alluvial soil. Such is a brief, and confessedly very imperfect, sketch of the general aspects of vegetation in Palestine and the surrounding countries. It seemed, however, needful to attempt to give an outline of the picture, as a whole, before proceeding to deal with the several elements of which it is composed.

|

|

|

|

|

1) Egypt and Syria; their Physical Features in relation to Bible History. By Sir J. W. Dawson (R.T.S., new and revised edition, 1887). 2) Geography of Plants. 3) Other writers have increased the number to twenty-two. 4) See Daubeny's Essay on the Trees and Shrubs of the Ancients (1865). 5) Byeways in Palestine. 6) See Deut. xx. 19, 20; Isaiah ix. 10; xiv. 8; xxxvii. 24; Jer. xxii. 7; Josephus, Wars, lib. v. c. iii. § 2; c. xi. § 1; lib. vi. c. i. § 1, 7) The Land of Gilead. 8) Tent-work in Palestine. 9) The Land of Israel. 10) Rob Roy on the Jordan. 11) Wars, lib. iii. c. x. § 8. 12) The sakkum tree of the Arabs, or False Balm of Gilead (Balanites Ægyptiaca). Wars, lib. iv. c. viii. § 3. 13) Psalm lxxx. 8. Cruden gives about forty references to the olive and the fig respectively; but more than three times as many to the vine. 14) Desert of Sinai. 15) An Ordnance survey of Sinai, under the direction of Major Palmer and Captain (now Colonel) Wilson, was successfully carried out in 1868-9, and the results of the investigations were published by government authority in five large volumes of letter-press, maps, and photographic illustrations; and subsequently epitomized in a useful handbook by Major Palmer. 16) Sinai and Palestine.

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD