By-Paths of Bible Knowledge

Book 10 - The Trees and Plants Mentioned in the Bible

Henry Chichester Hart, B.A. (T.C.D.), F.L.S.

Chapter 3

|

FRUIT TREES AND SHRUBS.

PALESTINE, with its varieties of climate and its fertile soil, was and is well

adapted for the cultivation of a corresponding variety of edible fruits. At the

present time this is actually the case, notwithstanding the insecure and

depopulated state of the country; but in Old Testament times the species of

fruit-bearing trees known to the Hebrews seem to have scarcely reached a dozen.

Several useful kinds, as the apple and pear, plum, orange, and peach, have been

introduced at a comparatively modern date; but the abundance and excellence of

the primitive produce more than compensated for its lack of variety. It was

peculiarly ' a land of vines and fig trees,' of 'pomegranates and oil-olive,'

and these were inferior to none of their kind; while there were others of

secondary importance, such as the carob-tree and the pistachia, which, beside

the common fig, were deemed worthy of being imported from the province of Syria into

Italy1. Of 'herbs' and 'vegetables,' in the common acceptation of those terms, we shall have to speak in a succeeding chapter.

The Israelites would naturally have brought from Egypt some knowledge of

horticulture; and when settled in their own land, we have sufficient hints in

the Old Testament writings for concluding that gardens and orchards were by no

means unusual among them. The picture of ' a watered garden' was a very common

one on the banks of the Nile, where irrigation was easy, and where lakes and

canals were readily constructed and maintained in a state of repair. The gardens

of the wealthier Egyptians were usually divided into sections, palm and

sycamore-fig trees forming the 'orchard,' apart from the trellised vines and

from the 'flower' and 'kitchen' plots. Solomon, perhaps for the gratification of

his Egyptian bride, laid out 'gardens and orchards,' in which he 'planted trees

of all kind of fruits ' (Eccles. ii. 5); and in the 'Song' ascribed to him (ch. iv. 12, 13; vi. II), a picturesque description is given of 'a garden enclosed,' watered by springs, and planted with

'nuts," pomegranates,' and other

'pleasant fruits.' And although such parterres are most frequently spoken of in

connection with royal palaces (2 Kings xxi. 18; xxv. 4; Neh. iii. 15, &c.), yet

other references clearly point to the possession of gardens and orchards by

private individuals, distinct from those more public plantations which may then

have surrounded the towns or villages of Palestine as they do at the present day

(cf. Isaiah lviii. 11; Jer. xxix. 5; xxxi. 12; Amos iv. 9 ix. 14, &c.). In

Cyprus—a truly Oriental island—even the poorer class of house has its garden of

orange, lemon, mulberry, and pomegranate.

'Summer fruits,' to which a special name (קַיִץ The practice of interment in gardens usually recalls the incidents of our Lord's burial and resurrection—the garden of Joseph of Arimathaea, and the 'gardener' to whose charge it seems to have been entrusted. But the custom, though well known to the Greeks and Romans, was evidently of much earlier date in Palestine, as appears from the mention of the burial-places of Manasseh and Amon, and, as it would seem, of Samuel and Joab also (2 Kings xxi. 18, 26; I Sam. xxv. I; I Kings ii. 34). Idolatrous observances, probably connected with social festivities, took place in gardens during the moral decline of the Hebrew commonwealth, and were sternly denounced by the prophet Isaiah (i. 29; lxv. 3; lxvi. 17). Modern travellers speak with enthusiastic admiration of the results of the diligent cultivation of fruit-trees in Palestine at the present day. Amidst the valleys and plains of the Lebanon district; in the warm coast-plain, at Jaffa, Ascalon, and Gaza; in the secluded vale of Shechem; in sheltered nooks amidst the hills that are round Jerusalem; in the once-famed Gardens of Solomon in the Wady Urtas, near Bethlehem; and in other spots too numerous to particularize, the beauty and fragrance, the excellence and productiveness of orchards, vineyards, and olive-groves proclaim in the silent eloquence of nature what the goodly land was in the days of her prosperity, and what, under a wise and equitable rule, she might yet again become. Of Syria Mr. Farley writes:—'The gardens are filled with the orange and the citron. Aleppo sends the far-famed pistachio to market, Jaffa produces the delicious water-melon; at Damascus there are plums, cherries, peaches of the finest kinds; and, above all, the apricot. In short, there is everything here to satisfy our material wants, to soothe the senses, and charm the imagination2.' ALMOND (Heb. שָׁקֵד shaked)

The Rosaceous order of plants, found in most parts of the world, but chiefly in the temperate regions of the Northern hemisphere, is rich in plants remarkable alike for beauty and utility. The roses of our hedgerows and flower-gardens, and the fruit-bearing trees in our orchards, are so closely allied as to be grouped in one family, as may easily be perceived by comparing the blossom of a wild rose with that of a cherry, apple, or plum tree. In Palestine the true roses are restricted to the northern mountains, where three or four species have been observed, but the entire order is represented by nearly sixty species. Among these are two fruit-bearing trees, of which the ALMOND (Amygdalus) first claims a brief notice. This beautiful tree is too well known to need detailed description, being a frequent ornament of our English gardens. The Hebrew name is peculiarly expressive, being derived from a verb ( שָׁקֵד shakad), signifying 'to watch for,' and hence 'to make haste.' Thus, in the vision of Jeremiah (i. 11), the prophet is shown 'a rod of an almond tree,' to signify that Jehovah ' will hasten' His 'word to perform it.' The symbol was a peculiarly expressive one, for early as the tree is to put forth its pinkish-white flowers in this country, it is in full bloom in Palestine in the month of January, and the fruit appears in March or April. The almond is still cultivated in Syria, and grows wild on the northern and eastern hills. Four species have been enumerated; but it was doubtless much more abundant in ancient times. Almond blossoms formed the pattern of the 'bowls' of the golden candlestick of the tabernacle (Exod. xxv. 33, &c.), and Aaron's rod was from the same tree (Numb. xvii. 8). As almonds were reckoned among 'the best fruits of the land' in the time of Jacob, and were sent by him to propitiate his unknown son in Egypt (Gen. xliii. 11), we may infer that they were not then cultivated in the latter country. Pliny, however, mentions the almond among Egyptian fruit-trees; and it is not improbable that it was introduced between the days of Jacob and the period of the Exodus. In connection with the earlier history of the same patriarch, we read that Jacob 'took rods of hazel' (Gen. xxx. 37). The word here used is (לוּז luz), which the Revisers, following the Rabbinical authorities and the analogy of the Arabic name, translate 'almond tree.' If this be correct, the ancient city of Bethel, which 'was called Luz at the first' (Gen. xxviii. 19), may have gained its original name from some conspicuous individual of this species. The beautiful symbol of old age in Eccles. xii. 5, 'the almond tree shall flourish,' is doubtless based on the snowy whiteness of its aspect when viewed from a distance; perhaps also, as Mr. Carruthers has suggested, with a reference to the still bare branches, resembling the withered limbs of the aged man, bending beneath a hoary head. So Moore has sung of . . .

'. . . . the silvery almond-flower

The almond no longer reaches us from Palestine; the 'Jordan almonds' of commerce

being grown in Malaga, and large quantities being exported from Spain. APPLE (Heb. תַּפּוַּחַ tappuach).

The ' apple' of Scripture, like the classical fruits of the Hesperides, has proved a source of much debate, if not actually an 'apple of discord.' The orange, citron, and quince have been proposed, as well as the more homely rendering in our English Version,—the Revisers in this case following their predecessors. It is advisable to look first at the requirements of Scripture itself. The apple tree and its fruit are mentioned six times in the Old Testament, but are not referred to in either the New Testament or the Apocryphal writings. Of the above six references, four are in Solomon's Song, one in the Book of Proverbs, and one in the prophecy of Joel. From the first group we learn that the tree was noted for its beauty, that its foliage afforded a grateful shade, and that its fruit was sweet and reviving (Song ii. 3, 5; vii. 8; viii. 5). In Proverbs xxv. 11, 'apples of gold in baskets, or filigree-work' (R. V.), are likened to 'a word fitly spoke;' and the prophet Joel (i. 12) bewails the withering of this among the other choicest trees of Canaan. In favour of the common interpretation, Dr. Thomson, as a long resident at Beirut, is entitled to be heard with the utmost respect. He says of the once renowned Philistine city of Askelon: Now the whole area is planted over with orchards of the various kinds of fruit which flourish on this coast. It is especially celebrated for its apples, which are the largest and best I have ever seen in this country. When I was here in June, quite a caravan started for Jerusalem loaded with them, and they would not have disgraced even an American orchard.' Adverting to the claims of the citron, he adds: 'Citrons are very large, weighing several pounds each, and are so hard and indigestible that they cannot be used except when made into preserves. The tree is small, slender, and must be propped up, or the fruit will bend it down to the ground. Nobody ever thinks of "sitting under" its "shadow," for it is too small and straggling to make a shade.' Such a criticism as this demolishes the claims of the citron; and the fruit of the quince is open to the same objection. The orange, also, seems to be an importation of modern times. But it is hardly so certain that the apple does, as Dr. Thomson goes on to maintain, 'meet all the demands of the Biblical allusions as to smell and colour.' Like the rest of the group to which it belongs, it affords a truly beautiful sight when laden with its early blossoms; yet 'apples of gold' seem to imply a deeper colour than that of even a 'golden pippin'3; and to perfume-loving Orientals, the odour of the apple would, in the writer's opinion, be deemed feeble and in operative. Dr. Tristram has vigorously pleaded the claims of the APRICOT (Armeniaca vulgaris) to be the apple of Scripture. As its name implies, it is thought to have been imported from Armenia into Western Asia and the South of Europe. Like the vine, it is not indigenous to Palestine, but has been cultivated and naturalized from very early times. Of the apple he observes, though cultivated with success in the higher parts of Lebanon, yet it barely exists in the country itself. There are, indeed, a few trees in the gardens of Jaffa, but they do not thrive, and have a wretched, woody fruit. The climate is far too hot for our apple-tree.' On the other hand, he says of the apricot: 'Perhaps it is, with the single exception of the fig, the most abundant fruit of the country. In highlands and lowlands alike, by the shores of the Mediterranean and on the banks of the Jordan, in the north of Judah, under the heights of Lebanon, in the recesses of Galilee, and in the glades of Gilead, the apricot flourishes, and yields a crop of prodigious abundance. Many times have we pitched our tents in its shade, and spread our carpets secure from the rays of the sun. There can scarcely be a more deliciously perfumed fruit than the apricot, and what can better fit the epithet of Solomon …as its branches bend under the weight, in their setting of bright, yet pale foliage?' This view has been adopted by other writers. A correspondent of the Daily Telegraph, writing from the island of Cyprus, gave the following additional particulars:— It will, I think, be a subject of interest to know that the identification of the fruit which in the Old Testament and in ancient Greek writings is called the "golden apple" has become possible. The three golden apples given by Venus to Milanion, whereby he won the race with Atalanta were plucked it is said, either from the garden of the Hesperides or from an orchard in Cyprus. Any proof helping to establish the identification of this fruit will come naturally with greater weight from Cyprus, the home of Aphrodite. In Cyprus at the present day, in early summer, almost every garden has trees laden with τά χρυσόμηλα, "golden apples," and the bazaars of the towns are filled with the fragrant fruit. The modern Greek name for apricot is τὸ βερύκοκκον, but the Cypriote still calls it by the ancient name τὸ χρυσόμηλο(ν), since he knows no other; thus carrying the mind back to the distant past when Cyprus was the garden of the Eastern Mediterranean, and fit to be the favourite residence of the Goddess of Beauty.' In judging of the claims of these two fruits, it must be admitted that the Arabic name for the apple is nearly identical with the Hebrew, while the apricot is called by the Persian name of mush-mush. But the apple cannot be said to be one of the choicer or more conspicuous trees or fruits of Palestine, nor, compared with others of its tribe, does it seem to warrant the implied compliment, 'As the apple tree among the trees of the wood, so is my beloved among the sons;' whereas the apricot was called by the Persians ' the seed of the sun,' and is reckoned as among the best of Syrian fruits in the Damascus markets at the present day. The balance of probability therefore seems to favour the apricot as the ' apple' of the Old Testament. This fruit gave names to two towns or villages of Palestine, one in the highlands of Judah, the other in the territory of Ephraim (Josh. xv. 53; xvi. 8). A descendant of Caleb also bore the same name (I Chron. ii. 43). CHESNUT (see previous Chapter). DATE PALM (Heb. תָּמָר tamar, Gk. φοῖνιξ).

Of those groups of trees which impress a definite character upon scenery, Humboldt places first the extensive family of the palms, 'the loftiest and most stately of all vegetable forms. To these, above all other trees, the prize of beauty has always been awarded by every nation, and it was from the Asiatic palm-world or the adjacent countries that human civilization sent forth the first rays of its early dawn. Marked with rings, and not infrequently armed with thorns, the tall and slender shaft of the graceful tree rears on high its crown of shining, fan-like or pinnated leaves, which are often curled like those of some grapes.' Above a thousand different species of palm have been enumerated by botanists, and some of these constitute the food-plants of whole tribes and nations. The cocoa-nut palm, the Mauritia palm of the Orinoco, and the date palm of Northern Africa and Western Asia, are examples. South America yields the most beautiful forms of this tree; but for combined grace and utility the DATE PALM of Egypt, Arabia, and Palestine merits all the praises that in ancient and modern days have been bestowed upon it. Palms flourish best in the tropics, but the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) lives as far north as those latitudes where the mean temperature is from 59° to 62° Fahr. Hence it is cultivated with success in the south of Spain and in Italy, but is not indigenous there, and the fruit seldom reaches perfection. Even in Cyprus, Mrs. Scott-Stevenson states that only in one district is the date palm fruitful, though the tree not uncommon.

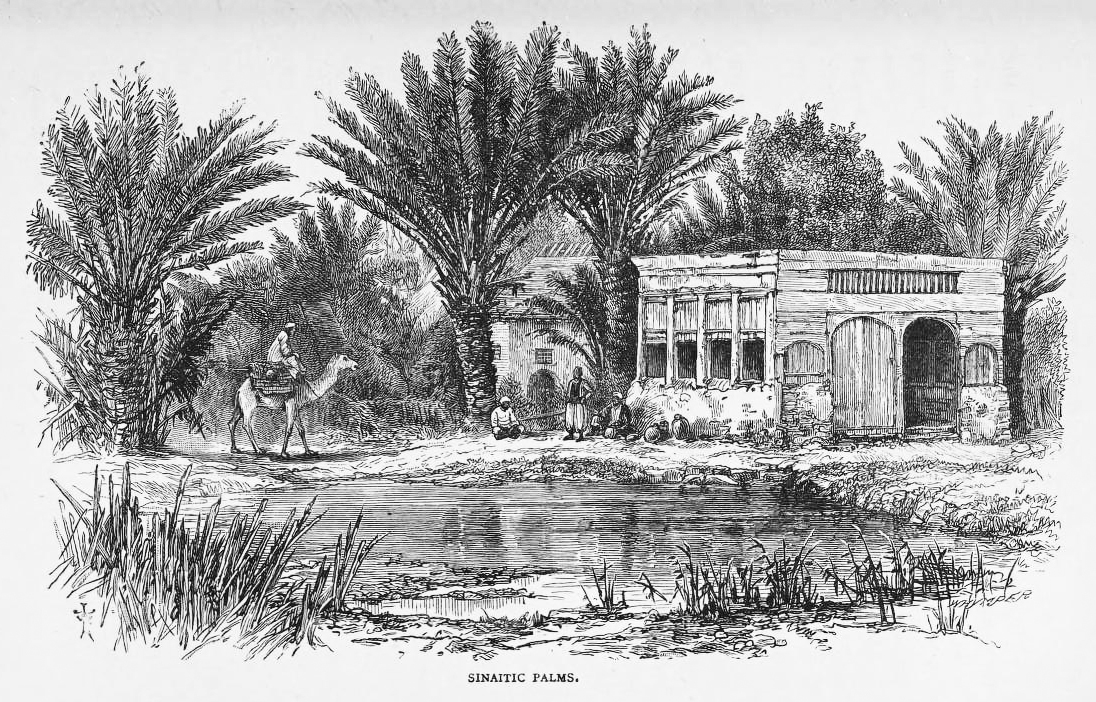

It is the chief ornament of the Sinaitic peninsula, and its presence renders

habitable by man whole districts that would otherwise be inhospitable wastes. In

the sandy plains of North Africa and the Arabian Desert oases of palm trees

occur, such as those of Elim, where the Israelite hosts encamped shortly after

quitting Egypt (Exod. xv. 27).

The palm, though not mentioned so frequently in Scripture as the vine, or even

as the olive or fig tree, is named in no less than fifteen different books of

the Old and New Testaments, beside giving names to persons and places (Tamar,

Baal-tamar, Hazezon-tamar) and a title to Jericho, 'the city of palm trees' (see

I Chron. ii. 4; iii. 9; Judges xx. 33; Gen. xiv. 7; Deut. xxxiv. 3). Its former

luxuriance and present rarity in that district have been already noticed

(Chapter I). Phoenicia, it will be remembered, was so named by the Greeks from

its palm trees (phoenix), and the date palm still grows in the warm maritime

plain. It occurs also in sheltered spots among the hilly regions, where

certainly it was more common in Biblical times. Nothing can more strikingly

exemplify the severity of the vicissitudes through which the country has passed

than the entire disappearance of that magnificent palm grove which made Jericho

famous, and whose praises were sung, not only by Jews like Josephus, but also by

foreigners like Strabo, Tacitus,

The date palm, both in its wild and cultivated condition, has been so often figured and described that the chief points relating to its structure, appearance and habits may be considered as well known even to the general reader. A visit to the Botanical Gardens at Kew will give a more accurate and impressive conception of the beauty and variety of the Palmaceae than either verbal or pictorial description. The practical uses of the date palm to the Arabs and other inhabitants of the regions in which it grows are almost innumerable. Not only is the fruit eaten raw or made into a conserve, but the young leaves, the soft interior of the immature stem, and the stamen-bearing flowers, are made available for food; while the sap is drunk as milk, and a spirituous beverage is distilled from it. The timber is valued for its durability, and the fibres of the leaves are converted into mats and baskets, sails and cordage. Even the hard kernels of the date are soaked in water and then ground up as food for camels5. Turning now to the Scripture references to the date palm, we find that it was formerly, as it is now in the East, the embodiment of grace and beauty, as the cedar was of strength and grandeur. Its lofty stature is referred to in the Song of Solomon vii. 7, and Jer. x. 5; its verdure and fruitfulness, even to old-age, in Psalm xcii. 12, 14. In Joel i. 12 it is spoken of among the most precious of fruit-bearing trees, while its beauty seems to have rendered it a favourite object of artistic design. It was freely introduced into the carved work of Solomon's Temple, and appears among the ornaments of the mystic edifice seen in vision by the prophet Ezekiel (1 Kings vi. 29; vii. 36; Ezek. xl. 26, 37, &c.)6 Ecclesiastically, the palm leaf was first used at the annual Feast of Tabernacles (Lev. xxiii. 40), and after the settlement of the Hebrews in Palestine these leaves were obtained from the Mount of Olives (Neh. viii. 15); and that the tree grew among the southern hills we learn from the mention of 'the palm tree of Deborah, between Ramah and Bethel, in Mount Ephraim' (Judg. iv. 5). The entry of our Lord into Jerusalem was signalized by the strewing of palm leaves in His triumphal path (John xii. 13), and the Romish Church annually commemorates the event, large numbers of palm trees being cultivated in Italy, Spain, and the south of France for the ceremonial on Palm Sunday. The long pinnated or winged leaves, reaching a length of twelve feet or more, form a striking crown to the tall and graceful stem of the cultivated palm; in the wild state the withered remains of each circlet of leaves adhere to the trunk, giving it a rugged appearance. In Jewish, Classic, and Christian symbolism, the palm leaf is the emblem of victory (Rev. vii. 9), and it occurs as a frequent and expressive sign above the resting-places of the persecuted believers who lived and died in the subterranean catacombs of Rome. The oases of Elim in the wilderness of the wanderings (Exod. xv. 27) derived its name from the 'trees' (אֵילִם elim), which we know to have been date palms. It is possible that Elath or Eloth, a port in the Gulf of Akabah (2 Kings xiv. 22, &c.), may have been so called from a similar grove, as palms are still found in that locality. Among the fruit-trees cultivated by the ancient Egyptians, 'palms,' says Sir G. Wilkinson, 'held the first rank, as well from their abundance as from their great utility. The fruit constituted a principal part of their food, both in the month of August, when it was gathered fresh from the trees, and at other seasons of the year, when it was used in a preserved state.' Palm wine, used in embalming, was probably made by tapping the tree, as now, and its wood and fibres were used in various ways for beams, tables, cordage, mats, baskets, brushes, ropes, and even toy-balls for children. The timber of the palms, however, is not adapted for the purposes of the carpenter or cabinet-maker, the wood being hardest at the outside and softest at the heart—a characteristic of that great division of plants which have straight-veined leaves. Sonnini, in his Travels in Egypt, describes 'a forest of palms and fruit trees' round Dendera, and 'a district covered with date trees' near Djebel-el-Zeer in Upper Egypt. He also mentions a spirit extracted from dates. The dates of Babylon were celebrated in ancient times for their especial excellence, and were reserved only for royal use7. Pliny mentions many varieties of this valued fruit, and Arab writers declare that there were three hundred names for the tree ---an Oriental hyperbole corresponding to the statement above-quoted as to its practical applications. FIG TREE (Heb. תְּאֵנָה teenah).

Our translators were on fairly secure ground when dealing with the chief fruit-trees mentioned in the Bible; and there is no uncertainty as to the identification of such vegetable princes as the Palm, the Olive, and the FIG TREE. From the frequent and varied references to the last-named tree we might safely infer its wide distribution and striking abundance in former times; but even now ' it grows wild in fissures of the rocks from Lebanon to the south of the Dead Sea,' and is cultivated in every available spot. From the source of the Jordan to the Judean hills, and from Moab to the shores of the Mediterranean, it spreads forth its broad and glossy foliage in vineyards, or among mulberries and pomegranates; and men, as of old, sit beneath its grateful shade. Or it grows green by the wayside, as when an unfruitful fig tree was made by the Great Teacher an affecting emblem of an unbelieving people. A fine grove occurs in the Wady et Tin, or 'Valley of Figs,' near the site of the ancient Bethel.

The common fig (Ficus carica) belongs to a genus of plants which comprises many remarkable members of the vegetable kingdom; such as the banyan, the peepul or sacred fig of India, the india-rubber tree, and the Australian fig. Most of the true figs secrete a milky juice, which is usually acid, and in some species highly poisonous. In the edible kinds the objectionable qualities are removed by cooking.

The order (Urticaceae) includes the elm and the mulberry, as well as herbaceous

plants like the hemp and nettle.

the edible fig of commerce. This species has a wide geographical range,

extending from the south of Europe to the north of India; growing also in

Northern Africa, where it has been known and valued from time immemorial, as the

monuments of Egypt conclusively show. The Biblical references to this tree

commence with the garden of Eden, and end with the visions of the Apocalypse.

Nearly all of them, however, illustrate either the frequency of its occurrence

throughout Palestine, the value of its shade, or the importance and excellence

of its fruit. The spies sent through the country by the order of Moses brought

back samples of grapes, pomegranates, and figs, as characteristic productions;

and these are again enumerated in the promise of Canaan (Numb. xiii. 23; Deut.

viii. 8). In Jotham's parable of the trees, the olive, fig, and vine are

selected as representatives (Judg. ix. 8-13). Prophets foretell their

destruction, and lament the desolation when accomplished. Thus Jeremiah: 'They

(the Babylonians) shall cat up thy vines and thy fig trees' (ch. v. i7); 'There

shall be no grapes on the vine, nor figs on the fig tree' (ch. viii. 13). Hosea:

'I will destroy her vines and her fig trees, and I will make them a forest' (ch.

ii. 12). Joel: ' He hath laid my vine waste, and barked my fig tree;' 'The vine

is dried up, and the fig tree languisheth' (ch. i. 7, 12). But in promises of

pardon and restored prosperity the fig and other trees are to 'yield their

strength' (Joel ii. 22); and, as in Solomon's halcyon reign (1 Kings iv. 25),

every man is to 'sit under his vine and fig tree' (Micah iv. 4; Zech. iii. 10).

For disobedience the locusts had attacked the olive-yards and vine-yards, and

gnawed the fig trees; but with repentance and reformation, vegetable life was to

be renewed (Joel i. 4; ii. 25; Amos In a vision of 'two baskets of figs,' recorded by Jeremiah, the captives of Judah are typified by the better sample of the fruit (ch. xxiv. 1—7); but the emblem is more specially used by our Lord, in whose teaching the barren fig tree points directly to the Jewish nation (Luke xiii. 6; Mark xi. 13, &c.). In the Gospel narrative we also find such incidental references as the single fig trees at Bethany and Cana, and the village of Bethphage,' signifying 'house of green figs' (Luke xix. 29; John i. 50; Matt. xxi. 19). We find also Scripture allusions to 'green' or unripe figs, and to the 'first-ripe' figs of the early summer (Song Sol. ii. 13; Jer. xxiv. 2), both of which were easily shaken from the tree (Nahum iii. 12; Rev. vi. 13). The first-ripe fig was esteemed a delicacy, as we may infer from the Revised Version of Isaiah xxviii. 4: 'as the first-ripe fig before the summer, which when he that looketh upon it seeth, while it is yet in his hand he eateth it up.' As a matter of fact, the fig tree, under favourable conditions, bears as many as three crops of fruit in the year: viz., the Early, appearing about March or April, and ripening in June; the Summer, appearing in June, and ripening in August; and the Winter, appearing in August, but ripening after the fall of the leaf. These latter often remain on the tree through the winter months. The fruit of this productive tree was not only, as now, a most important article of food when raw, but was also preserved by being pressed into cakes. In this form, figs were brought by Abigail to David and his followers; and also by the northern tribes to the festival at Hebron (I Sam. xxv. 18; I Chron. xii. 40). The Egyptian captured by David's men in their pursuit of the marauding Amalekites had cakes of figs given to him as a restorative (I Sam. xxx. 12); and it is worthy of notice that, according to the testimony of Pliny, who described nearly thirty varieties of this valued fruit, 'figs are the best food that can be taken by those who are brought low by long sickness, and are on the recovery.' The employment of figs as a medicament is illustrated in the narrative of King Hezekiah's illness (2 Kings xx. 7, &c.), which accords with both ancient and modern applications of this useful fruit. The Egyptians were fond of cultivating the fig tree, which, as in the imagery of our Lord's parable, is re-presented on the monuments as growing in the vineyards; and the fruit of both the common species and of the inferior sycamore-fig tree was deemed a fit present to the gods. Among the Hebrews, it is scarcely needful to state, first-fruits of all kinds were brought as thank-offerings. It is uncertain when the edible fig was introduced into this country; whether by the Romans, who set much value on the fruit, or as late as the sixteenth century. In favourable spots in the south of England the sweet produce comes to perfection, and far surpasses in delicacy of flavour the dried specimens imported from Turkey, Egypt, and the Mediterranean; but it often grows in gardens to the size of a tall shrub, being cultivated for the sake of its agreeable foliage. The wood is spongy and oily, though durable; and therefore of little value. Horace, in one of his coarsest Satires, speaks of a fragment which he calls inutile lignum, and says, derisively, that the carpenter, being unable to use it for a bench, made it into a god8, — a passage which recalls the fine description of idol-makers in Isaiah xliv. 9-17. One of the poet's commentators quotes a Greek proverb, 'As brittle as a prop of fig-tree wood;' and the same people had a phrase, 'figgy men,' equivalent to 'weak fellows.' It may be added that the fruit of the fig tree is one of those which, as modern research has so remarkably shown. owe their fertility to the agency of insects. It consists of an enlarged and fleshy receptacle, within which the small and insignificant flowers are clustered, leaving a small opening at the broader extremity, where the insect is enabled to enter and disperse the pollen or fertilizing dust. The flowers are succeeded by the tiny seed-like fruits with which the interior of the fig of commerce is lined. The Greeks forbade the exportation of figs from Attica; and any one who gave evidence that this law had been broken was call, a 'fig-informer;' whence our modern words 'sycophant' and 'sycophancy.' An old tradition asserted that it was on a fig tree in the neighbourhood of Jerusalem that Judas hanged himself, but this doubtful celebrity was by others attributed to the Cercis siliquastrum, a red-flowered leguminous tree, growing in Palestine and the South of Europe. Husks (Gk. κεράτια).

Among the minor fruit-trees of Palestine the CAROB or locust tree (Ceratonia siliqua) is widely distributed and admired for its dark and shining leaves. It is common in Galilee, in the plain of Sharon and around Acre, and in the ravines of Lebanon and the trans-Jordanic hills. It is specially conspicuous near Beirut, but is not found on the higher and colder situations. It is a leguminous or pod-bearing plant, its long brown beans not only being ground up for cattle and swine, but, on account of their eminently nutritious properties, both pod and seeds are eaten by the poor. The Arabs call them kharub, and there can be little doubt that they represent the 'husks' with which the Prodigal Son was ready to satisfy the cravings of hunger. The carob is also called the 'locust' and 'St. John Baptist's tree,' from an erroneous idea, adopted by some of the Christian fathers, that the pods or 'husks' formed the food of Christ's great forerunner, whose 'meat was locusts and wild honey.' A more accurate knowledge of Oriental foods has removed the supposed difficulty attached to the simpler interpretation. The tree is abundant in Malta, and in Cyprus, where it reaches enormous dimensions and forms groves; it is found, in fact, in all the Mediterranean area. A confection is made of the pulpy interior of the pods, which Pliny long since described as 'very sweet;' and which are not infrequently eaten, though the entire bean is chiefly used (as in Palestine) for cattle and for horses. It is still exported from Syria to Alexandria, and so into Europe, in large quantities. Dr. Daubeny considers that the carob was thus introduced into Italy. Though not a native of Egypt, it appears from the monuments to have been cultivated in the gardens of that enterprising race. NUTS (Heb. בָּמְנִים botnim, אֱנוֹז egoz).

The above brief passages constitute the sole references in Scripture to two important trees—the PISTACHIA and the familiar WALNUT, the edible fruits of which constitute articles of commerce in both Western Asia and Southern and Middle Europe. The PISTACHIA (P. vera) belongs to the terebinth order of plants (Terebinthaceae), and is indigenous to Palestine and Syria, where it is extensively cultivated for the sake of its nuts, which are exported from Aleppo and the ports of the Levant. The tree grows also in Southern Europe, where it has become naturalized for many centuries. The oily almond-like kernels are eaten as a dessert and made into a sweetmeat. There is little doubt that these were the 'nut'which formed part of the present forwarded to his unknown son by the Hebrew patriarch, the pistachia being a tree of the rocky highlands, and not growing in the valley of the Nile. The nuts were highly valued by the ancients, both for food and as a stomachic; and also as 'an antidote to the bite of serpents.' It is possible that the Gadite city, Betonim (Josh. xiii. z6), may have derived its name from these trees. The WALNUT (Juglans regia)' is too familiar an object to need description either of its general appearance or of the nature and value of its fruit or timber. It may suffice to remark that it is widely diffused, from the Himalayas through China, Persia, Northern Palestine, and the south-ern and central parts of Europe. It was introduced into England at least as early as the sixteenth century, and was formerly cultivated for the sake of its light, compact, and fine-grained wood; but since the introduction of mahogany and other foreign timbers, it has been valued chiefly for its wholesome and nutritious fruit. It is only, however, in the warmer parts of our island, or in very sheltered spots, that this tree ripens perfectly. On the Continent, not only are the nuts of vast importance as an article of diet, but the wood is largely used for gun-stocks, and an oil of superior quality is extracted from the seeds. A fermented spirit is obtained from the sap, and a brown dye from the husks and roots. Formerly the leaves and fruit were turned to account medicinally, as Cowley's quaint lines declare:-

This last allusion is to the celebrated Mithridates, who carried with him a secret prescription against poison, consisting of a conserve of walnut-kernels, figs, and rue. Pliny says that the Greeks called the fruit Persian and Basilican, whence he infers it to have been brought from Persia. The Romans called it juglans or 'Jupiter's nut' (Jovis glans). Cicero and Virgil both mention this tree; and the latter tells his husbandman to expect a good wheat harvest if 'the nut blossom plentifully and bend down its odoriferous branches9. It would seem that Solomon planted these fine trees in his gardens near Jerusalem, to which reference has already been made; and probably they were well known in later days, if not at an earlier period, although the fact is not elsewhere hinted at in Scripture. At the present time the walnut is cultivated in 'all the glens and lower slopes of Lebanon and Hermon.' It grows still in different spots in Galilee, and Josephus speaks of 'old trees ' in his day 'near the Lake of Gennesareth.' Dr. Thomson states that the wood is used for window-lattices in Damascus. OLIVE (Heb. זֵיִת zayith). OLIVE OIL (Heb. שֶׁמֶן shemen, יִצְתָר yitshar, מְשַׁה meshach).

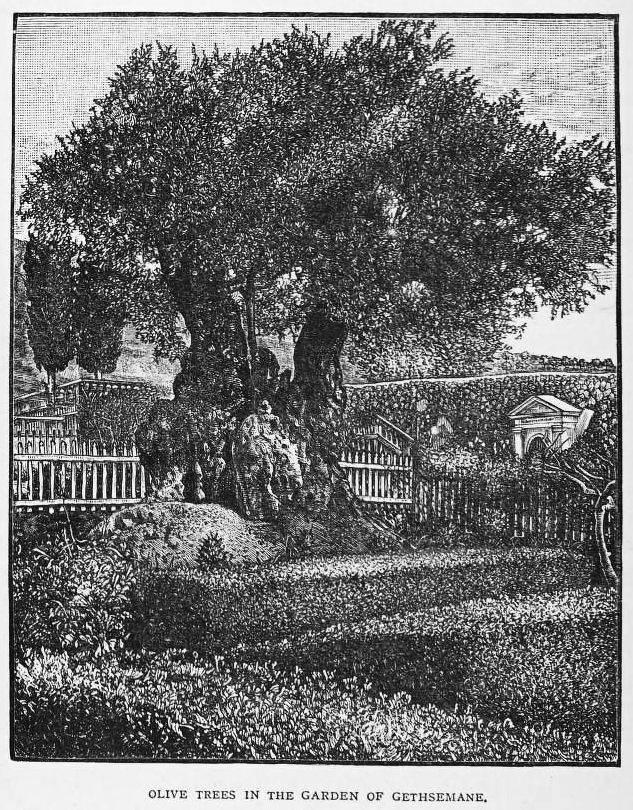

Regarded by the nations of the earth as a symbol of peace, reverenced by the Greeks as the special gift of the Goddess of Wisdom to man, and celebrated through-out the sacred volume for its beauty and its fruitfulness, it is scarcely an exaggeration to entitle the OLIVE, as did the old Roman agriculturist, 'the first of trees10.' Its geographical area comprises the countries bordering the Mediterranean; but while in Egypt it is comparatively poor, it flourishes in Palestine to an extent and with a luxuriance which make it, to the eye of the modern traveller, the characteristic tree of Israel's heritage. There, in the calcareous and often rocky soil, the olive strikes deep its roots, lifts its gnarled stem, and spreads forth its fresh grey-green foliage, with a beauty all its own. Only on the bleak mountains, and in the hot Jordan valley, is it absent. Elsewhere it is cultivated with increasing care, and would be extensively planted but for the oppressive tax laid upon every tree, which practically prohibits an investment of labour and capital for a profit so distant, the olive not becoming fruitful until the age of twelve or fourteen years. It grows, as in former days, around Jerusalem, and studs Mount Olivet, though in diminished numbers; it creeps along the hill-sides, and in the warm plains and sheltered valleys almost literally fulfils the ancient declarations:—'The rock poured me out rivers of oil;' 'He made him to suck oil out of the flinty rock' (Job xxix. 6; Deut. xxxii 13). In the north, olive-yards spread out amidst the valleys of Lebanon and Galilee. The rich coast-plains and the valleys that open into them recall the promise to Asher, 'Let him dip his foot in oil' (Deut. 24). On the east, Gilead and Bashan retain their olive plantations, and the tree grows wild in the gorges and on the hill-sides. The 'fat valleys' of Ephraim (Isaiah xxviii. i) still prove how 'pleasant' was the abode of that once-favoured tribe (Hosea ix. 13). Ebal, Gerizim, and Tabor; Carmel and Sharon; Ramah, Hebron and Bethlehem,—are adorned with the labour of the olive; and as when the sorrowing Saviour 'knelt to pray,' the 'olive-shade' still overhangs the Garden of Gethsemane. We know that the ruthless hands of the Roman soldiery spared no available tree in or near the beleaguered city; yet the 'aged olives' which so many modern travellers have described may be the direct descendants of those which sheltered the Son of Man in His hour of agony; since this vigorous tree will put forth new shoots after the stem has been lopped. In the island of Cyprus, where the tree abounds, an aged trunk, so decayed that scarcely more than the outer ring of bark appears to be left, will renew its youth by sending down roots, banyan-like, from the branches.

Concerning the olives now remaining in the Garden of Gethsemane, Lamartine thus

character-istically wrote:- A low wall of stones, without cement, surrounds this field, and eight olive trees, standing at about twenty or thirty paces distance from each other, nearly cover it with their shade. These olive trees are amongst the largest of their species I have ever seen: tradition makes their age mount to the era of the incarnate God, who is said to have chosen them to conceal His divine agonies. Their appearance might, if necessary confirm the tradition which venerates them: their immense roots, in the growth of ages, have lifted up the earth and stones which covered them, and rising many feet above the surface of the soil, offer to the pilgrim natural benches, upon which he may kneel, or sit down to collect the holy thoughts which descend from their silent heads. A trunk, knotted, channelled, hollowed, as with the deep wrinkles of age, rises like a large pillar over these groups of roots: and as if overwhelmed and bowed down by the weight of its days, it inclines to the right or left, leaving in a pendent position its large interlaced, but once horizontal branches, which the axe has a hundred times shortened to restore their youth. These old and weighty branches bending over the trunk bear other younger ones, which rose a little towards the sky, and had produced a few shoots, one or two years old, crowned by bunches of leaves, and darkened by little blue olives, which fall like celestial relics at the feet of the Christian traveller.' Such is the olive tree in modern Syria; and the remains of oil-presses in parts of the country where the tree is no longer cultivated, together with more than a hundred and seventy references in the Bible to olives and oil, testify to the abundance and value of these productions in ancient times. The modern Arabs have a curious proverb: 'The Jews builded; the Greeks planted; and the Turks destroy.' In reference to the second assertion, they point to such ancient olive plantations as are formed in regular rows, as the work of the Greeks. Miss Rogers (Domestic Life in Palestine), who quotes this saying, observes that the contrast is striking between these grey avenues and 'the wild wood-like picturesqueness of younger olive plantations now fruitful and flourishing, as well as to the still more ancient trees now falling to decay.' The olive is the chief representative of the order Oleaceae. It is a comparatively small tree, growing to a height of about twenty feet; the leaves are oblong, and their under-surface is hoary. The blossoms consist of small, whitish, and fragrant clusters produced in great profusion. The fruit is soft and oily, of a violet colour when ripe, and enclosing a hard kernel; unlike most other fruits, it is the fleshy exterior and not the seed which yields the oil. This rich and valuable juice is obtained by pressure. 'Virgin oil,' the best of which comes to us from Nice and Genoa, is that of the first-ripe fruit; further pressure gives the ordinary quality; and a still inferior kind, used only in the manufacture of soap, is yielded by boiling and squeezing the husk. From ten to fifteen gallons are obtained from each full-grown tree; but the olive does not reach its maturity much before its fortieth year. The fruit is exported from France, Spain, and Portugal, preserved in brine. The wood is fine-grained, and capable of taking a good polish; it is still employed in Palestine for cabinet-work. As already explained (see OIL TREE in Chapter II), Solomon's carved cherubim appear to have been made of the wood of the Eleagnus, though rendered 'olive tree' by our English translators; but it is unlikely that so fine-grained a material as olive-wood should have been overlooked by the Hebrew carpenters. In Cyprus, an olive-branch is often thrown upon the ignited charcoal of the braziers used for warming rooms, so that it may diffuse an agreeable fragrance through the apartment. Humboldt observes that the olive tree flourishes best between lat. 36° and 44°, but cold is more fatal to it than heat. It has been known in Greece from time immemorial, and is mentioned by Homer; it was brought thence into Italy, we are told, in the reign of the first Tarquin, and it was introduced into our own island in the reign of Elizabeth. Two points of special value attach to this fruitful tree; the one is its power of flourishing in a poor soil, the other its slight demands on the care of the husbandman. Both Virgil and Columella advert to these advantages11. The prophet Habakkuk, in a passage already quoted, says that even if 'the labour of the olive'—generally so soon rewarded by a plentiful crop—should 'fail,' he still will rejoice in God (ch. iii. 17, 18); and the earlier references to 'oil out of the flinty rock' have been cited above. The passages in which 'corn, wine, and oil' are mentioned as the representative productions of the land are too numerous to quote. When prosperity is illustrated or promised, the oil-vats 'overflow' and a blessing comes down upon the land, so that the rich produce of vine-yards and olive-yards are gathered in their season. But when judgment is foretold or described, the olive 'casts its fruit' and the oil 'languisheth' (Deut. vii. 13; xxviii. 40; Joel i. 10, &c.). The olive is said to grow best when at no great distance from the sea, and Solomon's chief plantations appear to have been near the coast-plain, on the ' Shephelah' or low hills between it and the central highlands (1 Chron. xxvii. 28). The fresh verdure and fruitfulness of the tree render it a fit emblem of the righteous man (Psalm lii. 8; Hosea xiv. 6), and the young plants shooting up from the soil around the parent tree are graceful types of the children of his household (Psalm cxxviii. 3). The patriarch Eliphaz says of the wicked, 'He shall cast off his flower as the olive' (Job xv. 33), alluding to the profusion with which the blossoms sometimes fall from the tree. The gathering of the fruit was accomplished by beating the branches, by which means some olives were always left out of easy reach. This is 'the shaking of the olive' alluded to by the prophet Isaiah: 'two or three berries in the top of the uppermost bough, four or five in the outmost fruitful branches thereof' (ch. xvii. 6). Although 'the labour of the olive' is so light, it is not wholly unnecessary; the tree has to be grafted in its wild state, or the fruit is small and worthless. St. Paul uses this fact with striking force in showing the obligations of the Gentiles to the true Israel (Rom. xi. 17, &c.), showing that it is 'contrary to nature' to graft a wild scion upon a good stock. Of the varied applications of the oil Scripture affords abundant examples. It formed the basis of most ointments and many perfumes. It was used privately for refreshment of the body, and publicly in official ceremonies. Kings, priests, and prophets were anointed with oil, and even the name of Messiah — Christ — originated with this custom. It was offered in sacrifices, and it supplied the sacred lamp of the Tabernacle and Temple as well as the humbler means of illumination in private dwellings. It was food and medicine, and ministered alike to the enjoyments of the rich and the sustenance of the poor. A few references are given as illustra-tions: Gen. xxviii. 18; Exod. xxvii. 20; xxviii. 41; Lev. ii. 1–7; I Sam. x. 1; I Kings xix. 16; Matt. xxv. 3; Mark vi. 13; Luke vii. 46 and x. 34: also Prov. xxvii. 9; Eccles. x. 1; Isaiah i. 6 (oil is here and in other similar passages rendered 'ointment'). It is a significant proof of the abounding fruitfulness and value of this tree, that in the 'Ten Precepts' ascribed by the Jewish Rabbis to Joshua, one of them, which allows a branch to be taken from a tree, specially excepts 'the boughs of the olive.' In Old Testament symbolism the olive denotes outward prosperity and rejoicing; but in the New it is emblematic of that 'heavenly unction from above’ of which the Jewish anointing of priests and kings was the feeble though fitting type. Among classical nations the olive crown and the olive branch symbolized respectively triumph and peace Victors at the Olympic games received a wild-olive wreath; and at the Pan-Athenaic festival, held in Athens in honour of Minerva, the producer of the olive tree, the aged men carried olive branches to the temple, and the successful competitors were rewarded with a vase of sacred oil. So also the Egyptian soldiers, after a successful campaign, carried twigs of olive in procession and offered them on the altars of the gods. In modern Cyprus a sprig of olive is hung over the doors of the houses on New Year's Day, as an omen of good-fortune. POMEGRANATE (Heb. רִמּוֹן rimmon).

This beautiful shrub appears at an early date in the history of food, art, and commerce. It was known as a favourite fruit in Egypt before the Exodus, for the Israelites murmured because the Idumean wilderness was ' no place of seed, or of figs, or of vines, or of pomegranates' (Numb. xx. 5). The robe of the Jewish high priest had an embroidery of 'pomegranates of blue and of purple, and of scarlet, round about the hem thereof;' and the same device appears again on the carved work of the pillars for the porch of the first Temple (Exod. viii. 33, 34; I Kings vii. 18, 20). The old Greek writers on botany and medicine, Dioscorides, Theophrastus, and Hippocrates, speak of the rind of the fruit being used as an astringent, and the bark of the root as an anthelmintic, a property known at the present day in both the East and West Indies. By the Greeks the plant was called ῥόα or ῥοιά, and is supposed to have given its name to the Isle of Rhodes. The Romans called it Punica or Punica malum, having obtained it from Carthage. In several of the archaic sculptures from Lycia in the British Museum, deities are represented holding the flower or the fruit of the pomegranate in their hands, probably as emblems of fertility. So in the Assyrian bas-reliefs, attendants on Sennacherib carry pomegranates and other fruit. The POMEGRANATE (Punica granatum of modern botanists) is a beautiful shrub, with dark and shining leaves and bell-shaped flowers, having both petals and calyx of a deep-red colour. In the autumn it yields a ruddy fruit about the size of an orange, filled with a delicious pulp, in which the semi-transparent seeds lie in rows. Dr. Thomson says that some of the pomegranates of Jaffa are as large as an ostrich egg. They ripen in September or October, and if hung up, will keep good through the winter. The pomegranate was included in the promise of fruit-bearing trees to the Israelites (Deut. viii. 8), and there is no doubt that it was formerly abundant in Palestine. It seems to be indigenous in Gilead, and is cultivated throughout the land, from Lebanon to Jericho. Dr. Thomson mentions a variety in the north which is quite black externally, but the usual tint is reddish, as may be inferred from the Oriental compliment repeated in Song of Solomon iv. 3; vi. 7. These shrubs often grow with fig trees near wells, while abounding in the gardens in and near the different towns and villages. An 'orchard of pomegranates with pleasant fruits,' and a 'garden of walnuts' with 'vines' and 'pomegranates,' are referred to in the same highly-coloured poem (Song iv. 13; vi. 11; vii. 12). As of old, 'spiced wine of the pomegranate' (ch. viii. 2) is made from the fermented juice, which is also drunk as a cooling beverage; and the seeds are served as a dessert, moistened with wine and sprinkled with sugar. It still grows in the once luxuriant Gardens of Solomon. The prophet Joel bewails the 'withering' of the pomegranate, while Haggai promises its increase to the remnant of the Captivity (Joel i. 12; Haggai ii. 19). This tree gave its name to several cities, as Rimmon or Ain Rimmon ('spring of the pomegran-ate'), now called Um-er-Rumamin ('mother of pomegranates'), in the inheritance of Simeon on the south (Josh. xix. 7); Rimmon or Remmon in Zebulon in the north (ver. 13); and the 'rock of Rimmon,' to which the defeated Benjamites fled (Judg. xx. 45). Also to one of the stations of the Israelites in the wilderness —Rimmon-parez (Numb. xxxiii. 19). Saul encamped 'under a pomegranate tree,' which must have been near to the Rock of Rimmon (I Sam. xiv. 2). The Egyptians prized and cultivated the pomegranate in their gardens; and, as already hinted, it was well known to the ancients. Pliny mentions varieties of the fruit, the use of the blossoms for dyeing, of the rind for tanning leather (as now in Morocco), and of both fruit and flowers in medicine. Grenada in Spain is supposed to have derived its name from the pomum granatum or seeded fruit,' and the arms of the province are said to be 'a split pomegranate.' The tree flourishes in the West India islands, into which it was long since introduced; but its native area extends from the Himalayas to the Caucasus. The pomegranate is too delicate a plant for any but the warmest parts of our own island; and even there it is cultivated simply for its foliage and flowers. It was introduced about 1548, and is mentioned by Lord Bacon, who recommends the juice of the sweet varieties of the fruit as a remedy for 'disorders of the liver.' The rind of the fruit, and the root, are still prescribed, in the form of decoctions, by English physicians. SYCAMINE (Gk. συκάμινος) SYCAMORE (Heb. שִׁקְמָה shihmah, Gk. συκομωραία).

In giving almost identical names to the mulberry (συκάμινος) and (συκόμορον), the sycamore-fig, the old Greeks were not led into any serious botanical error; for both the figs and the mulberries are classed by most botanists in the same order of plants. Both terms were derived from, συκῆ, a fig, and the sycamore is the ' fig-mulberry,' so called from its resemblance to the fig in its fruit and to the mulberry in its leaf. The 'Morea' derives its name from its similarity to the latter in form. But the two names were often used inter-changeably, the sycamore-fig being called the 'Egyptian sycamine.' By Latin writers the two kinds were distinguished by different names. Modern Biblical critics have contended that their predecessors were in error in supposing the 'sycamine' of Luke xvii. 6 to be identical with the ' sycamore' of Luke xi. 4, and of the half-dozen references thereto in the Old Testament. But although, as we have seen, translators of former days fell into many excusable mistakes in matters of scientific identification, two points may fairly be urged in their favour in the present instance. The first is, that in the Septuagint Version of the Old Testament every instance in which the Hebrew has shikmin the Greek has συκάμινος, 'sycamine,' and not 'sycomore,' though the fig, and not the mulberry, is certainly intended. St. Luke, therefore, may easily have used the two names interchangeably. The second argument is forcibly put by Dr. Thomson: 'As to the mulberry, it has yet to be shown that it was then known in Palestine; . . . and further, the mulberry is more easily plucked up by the roots than any other tree of the same size in the country, and the thing is oftener done. Hundreds of them are plucked up every year in the vicinity and brought to the city for firewood.' We conclude then that the word sycamine, instead of being used in its strictly classical sense in the passage above cited, is employed, as in the Old Testament, to denote the SYCOMORE-FIG, and as synonymous with the συκομωραία of Luke xix. 4. The tree thus alluded to is a true fig, and has no natural alliance with the maple sycamores of Europe and North America, which belong to an order not represented in Palestine. It is the Ficus sycomorus of botanists, and is still common in warm and sheltered localities in that country. In Egypt 'Pharaoh's fig trees,' as they are called, are less abundant than formerly, leading some modern travellers to doubt, but quite unnecessarily, whether this was the true 'Egyptian sycamore' of Theophrastus and Dioscorides. Dr. Thomson has given a full description of this noble tree of wayside, valley, and plain. He says it is easily reared, grows rapidly, and becomes a giant in girth, with wide-spreading branches and enormous roots. It bears several crops of figs during the year; but they are small and insipid, compared with those of the better-known F. carica. Still, they are gathered, as by the prophet Amos of old, and sent into the markets for food, chiefly among the poorer classes; among whom alone ' gatherers of sycamore fruit ' are to be found (see Amos vii. 14). Children, like Zaccheus, often climb into the branches. In flowers and foliage it closely resembles the common fig, but grows to a greater size, sometimes reaching a height of thirty or forty feet, and a diameter of twenty. The wood is soft, but durable, and therefore useful; and this fact will serve to explain several Biblical allusions. David, and Solomon after him, had special plantations of sycamores and olives under the care of crown officials, in the 'Shephelah' or low hills near the coast, where the climate is mild and equable (1 Chron. xxvii. 28; 1 Kings x. 27). Solomon in his years of wealth and prosperity made cedar timber as common as sycamore wood. In later times, when national apostasy had brought divine judgments on the land, Ephraim and Samaria are represented as saying, 'in their pride and stoutness of heart,'—' the bricks are fallen down, but we will build with hewn stones: the sycamores are cut down, but we will change them into cedars' (Isaiah ix. 9, 10). With cedars, pine trees, and oaks, the Hebrews might well regard the wood of the sycamore-fig as an inferior material; just as the fruit was not to be compared to that of the allied species. But in Egypt it was far otherwise. The sycamore yielded the largest planks; it was extensively cultivated for coffins, tables, doors, boxes, tablets, and idols; while as a fruit-tree its figs were valued much more highly than in Palestine, being included in the sacred offerings to the gods, and even selected as the heavenly fruit to be given to the righteous on their admission to eternal happiness. Hence we can well understand the severity and significance of the visitation mentioned by the Psalmist (lxxviii. 47): 'He destroyed their vines with hail, and their sycamore trees with frost.' Like the statelier palm, the sycamore has almost disappeared from the city of Zaccheus the publican. An aged specimen grows near the Pool of Siloam at Jerusalem, and is said to mark the site of Isaiah's martyrdom. VINE (Heb. נֶּפֶן gephen, Gk. ἄμπελος).

If the Olive be the most abundant and characteristic tree of Palestine, the VINE has been from ancient days the chief type of Israel and of Israel's inheritance. On coins and sculptured monuments, on temples and tombs, in the writings of prophets and psalmists, and in the teachings of Him who was emphatically 'the True Vine,' this lowly but fruitful shrub is interwoven with the thought and history of the chosen people. The Syrian climate, soil, and water-supply all favour, in a peculiar degree, the cultivation of the grape; and this branch of industry has been practised in the East from the very dawn of history, as we learn from one of the earliest chapters of the Book of Genesis. In like manner vineyards were planted in Asia Minor and the south of Europe before the days of Homer; while the Egyptian and Assyrian monuments attest their former abundance on the banks of the Nile, and in the great empires of the Farther East. We need not wonder, therefore, that in classic fables the Egyptian Osiris and the Greek Dionysus were credited with the first bestowment of the vine, as Minerva of the olive. It abounds in Cyprus, some five and thirty square miles of that interesting island being planted with this richest of fruit. Yet the botanical home of the vine ' must be sought in the regions between Caucasus, Ararat, and Taurus.' Here,' says Dr. Royle, 'as well as in the elevated valley of Cashmere, the vine climbs to the top of the loftiest trees, and the grapes are of fine quality and large size, in many places of the intermediate country.' Of its economic uses the same writer concisely adds: 'Every part of the vine was, and still continues to be, highly valued. The sap was at one time used in medicine . . . When ripe the fruit is everywhere highly esteemed, both fresh and in its dried state as raisins. The juice of the ripe fruit, called must, is valued as a pleasant beverage. By fermentation, wine, alcohol, and vinegar are obtained; the lees yield tartar; an oil is sometimes expressed from the seeds; and the ashes of the twigs were formerly valued for their potash.' Its range is wider than that of the other conspicuous fruit-trees of Palestine; yet it will neither bear extreme heat on the one hand, nor combined cold and damp on the other. In the Eastern hemisphere its limits extend from the equator to latitude 50°, or even higher; in the Western hemisphere it reaches only 40° from the equator. Between 30° and 35°—a region including of course Syria and Palestine—the vine reaches its highest perfection. In Europe, however, the products of the French vineyards are reckoned superior to all others, in quantity and quality. English vines are mentioned by the Venerable Bede and in Doomsday Book, and were probably introduced some centuries earlier by the Roman colonists of Britain. The island of Ely was called 'Isle of Vines' by the Normans, and grape orchards are frequently mentioned in connection with monasteries. Bishop Grindal sent presents of grapes to Queen Elizabeth from his gardens at Fulham; but from about that period the cultivation of the fruit appears to have declined. Those now celebrated for their size or productiveness are grown under glass, as at Hampton Court. Prof. Schouw says that the greatest number of bunches known to have been cut from a single plant was in the case of a vine at the Rosenberg Gardens at Copenhagen, which yielded no less than 419, weighing 610 lbs. In the south of France there were said to be instances of bunches weighing from 6 to 10 lbs. each, and a traveller in Palestine relates that they are to be met with there up to 17 lbs.12' The general aspects of this plant,—its graceful foliage, clasping tendrils, fragrant though inconspicuous blossoms, and clustered fruit,—are too well known to need description; but it may be remarked that soil and cultivation have given rise to varieties which may be numbered by hundreds, while the flexible stems and boughs can be trained in the most diverse ways to suit the taste or convenience of the husbandman. No product of the field is more bountiful or compliant, yet none has been so irrationally and fatally abused. In estimating the predominance of vineyards as a feature in the scenery of ancient Palestine, and an element in the sustenance of its once teeming and prosperous inhabitants, we must remember not only the ravages of successive invaders from the Babylonians and Assyrians onward, and the destructive effects of atmospheric agencies upon a thin soil artificially cleared of timber; but also the fact that the Saracens, following out the Mahometan prohibition of the use of wine, uprooted the vines,' as an old writer asserts, when they overran the country. A later traveller, the shrewd and accurate Maundrell, who visited the Holy Land in 1697, comments, as many since his time have done, on the bare aspect of the southern hills; but gives the true key to the difference between modern and ancient Judea, in the loss of the needful soil through neglect; and adds the opinion that these rocky slopes were just adapted for olive and vine culture. And yet, in spite of past injuries and present misgovernment, the vine is cultivated throughout the land, from Lebanon to Hebron, though of course in diminished numbers. Vineyards dot the hill-sides with miniatures of beauty and luxuriance; the laden branches trail on the ground as in some parts of the Lebanon district, climb the walls of rude stone, or are trained on trellises in gardens and court-yards, as now at Jericho, forming delightful arbours—a 'shadow from the heat,' and a protection from the ' sun' that 'smiteth by day.' Remains of rock-hewn vine-presses, and of towers built for the protection of the husbandman, occur more or less frequently throughout the hills of Palestine, and tell the same silent but impressive story as the oil-presses already referred to. It is equally suggestive to note that Nature has in some instances resumed her sway, oaks and lentisks having sprung up where once the vines of Israel flourished. If we include the products of this 'plant of renown,' as well as the plant itself, the various Biblical allusions to the vine will number more than four hundred. It will not therefore be possible, even were it necessary, to quote more than a few of those passages which seem to call for special remark. As to the geographical range of the vine in Old Testament times, we readily gather such facts as the following:—It is first mentioned in connection with Ararat, its primitive habitat, where, as we are informed, the patriarch Noah planted a vineyard (Gen. ix. 20). We next read of the vine as a familiarly known and cultivated plant in Egypt, as illustrated in the dream of Pharaoh's 'chief butler' (ch. xl.), and of the destruction of the Egyptian vineyards by hail-storms (Psalm lxxviii. .7). The extent and importance of this industry are abundantly and graphically depicted on the monuments, where the whole process of training the vines—usually on trellis-work supported by pillars—of gathering the fruit, and of converting it into wine, is exhibited. In prophetic language, Israel itself was a vine brought out of Egypt (Psalm lxxx. 8). In the insulting challenge of Rabshakeh, or rather the Rabshakeh (i.e. the chief cup-bearer) of Sennacherib to the Jews in the reign of Hezekiah, he offers to 'take them away' to a land like their own—'a land of corn and wine, a land of bread and vineyards' (2 Kings xviii. 32). So also, somewhat later in the history, Belshazzar and Xerxes had their 'banquets of wine,' Nehemiah appears as cupbearer to Artaxerxes, and Nahum and Habakkuk denounce the Ninevites and Chaldeans for their shameful intemperance (Dan. v. 1, 2; Neh. i. 11; Nahum iii. 11; Habak. ii. 15, 16). In accordance with these passages we find the use and abuse of the fruit of the vine repeatedly exemplified on the Assyrian sculptures. The culture of the vine by the Canaanitish races, anterior to the Hebrew invasion, is manifest from such incidents as the meeting of Abraham and Melchizedek, the report of the spies, and the allusions of Moses to the promised inheritance (Gen. xiv. i 8; Numb. xiii. 20, 24; Deut. vi. II). And even at that early period the district in which this branch of agriculture reached its highest perfection in Southern Palestine may be inferred from the patriarchal promise to Judah: Binding his foal unto the vine and his ass's colt unto the choice vine;' while the well-loved Joseph is compared to the 'fruitful bough' of a vine growing 'by a well, whose branches run over the' stone 'wall' of the terraced plantation (Gen. xlix. 11, 22). The valley of Eshcol (grape cluster) yielded the huge sample of grapes carried to Moses by the spies, and received its name from the circumstance (Numb. xxxii. 9). The valley of Sorek (vineyard) in the Philistine plain was similarly named (Judg. xiv. 5; xv. 5; xvi. 4). So also the plain of the vineyards' (Abel-keramim), east of Jordan (ch. xi. 33). Later on, the vineyards of Engedi, on the western shore of the Dead Sea, are specially mentioned (Song of Solomon i. 14); and Jeremiah laments for the wasting of the Moabite vineyards of Sibmah (ch. xlviii. 32). The wine of Helbon in Anti-Lebanon was exported to Tyre, according to Ezekiel (xxvii. 18); and the 'scent of the wine of Lebanon' is alluded to by Hosea (xiv. 7). In our own day, Canon Tristram reports that the raisins of Eshcol are delicious; Mr. Fisk mentions the luxuriance of the vines of Hebron, whose fruit, according to Dr. Thomson, is finer than those in most other parts of the country. Buckingham and earlier travellers declare that the wines of Lebanon are in no degree inferior to the best of those in France. At Engedi (Ain Jidy) the terraces still remain, though the vineyards have disappeared. And, as of old, the 'wild vine,' which is to the cultivated kind what a crab-apple is to a pippin, still overspreads ruins and waste places, bearing its 'sour grapes,' which no man cares to eat. Mr. Smith13 thinks that a variety or species known as the Oriental vine (V. orientalis), producing a small acid fruit, may be the 'wild vine' of the prophecies, and possibly the 'de-generate plant of a strange vine' (Isaiah v. 2; Jeremiah ii. 21). This, however, is certainly not the 'wild vine' of 2 Kings iv. 39, which was manifestly a poisonous herb (see WILD VINE, Chapter IV). It is needless to quote passages for the purpose of proving the extent and importance of the vine, and the value attached to its produce in Palestine, during the long periods covered by Old and New Testament history; or to the abundance and excellence of the Syrian vintage. It will suffice to mention the original promises made to the Israelites before they had been consolidated into a nation; the imagery of psalm and prophecy; and the fact that no less than five of the parables of the Great Teacher relate to vines and their culture. Equally significant is it to note that about a dozen words are found in the Hebrew and Greek languages (chiefly the former) to denote this plant and its uses. Nor does it fall within the compass of the present work to detail the processes of this or any other branch of agriculture. A few points, however, deserve special reference. The pliancy and adaptability of which we have already spoken were fully recognized by the ancient inhabitants of Palestine. They imitated the Egyptians in training the vines over trellises, and their grateful shade was the emblem of prosperity and peace. The character of the soil taught the Canaanites and their successors the construction of terraces. In the court-yards of large houses, and on the walls of cottages, the vines spread their interlacing tendrils; and it is probable that they were also allowed to climb round fig and other trees. In the north, they are and probably were trained along the ground with but slight support (Psalm lxxx. 10; cxxviii. 3; Ezek. xvii. 6). As now, the vineyards were surrounded with walls of rude stone or with a hedge, or both (Isaiah v.5; Mark xii. I). Between such walls Balaam rode. 'Cottages,' or huts, of rough unhewn stone, roofed with earth, are built for the keepers, as in Old Testament days; and more substantial 'towers' were erected whence a look-out might be kept against the depredations of man or beast, of prowling robber or 'boar out of the forest,' or the young jackals that 'spoiled the vines' (Isaiah i. 8; v. 2; Matt. xxi. 33 Psalm lxxx. 13; Song of Solomon ii. 15). The autumnal vintage, like the grain harvest which preceded it, was a season of special rejoicing (Isaiah xvi. 10; Jer. xxv. 30). The general arrangements are described in Isaiah's parable (ch. v.), and in that of our Lord (Mark xii. 1, &c.). The poor were allowed to glean in the vineyards, as in the corn-fields (Lev. xix. 10); the 'vine-dressers' also belonged to the poorer classes (Isaiah lxi. 5). Beside the ordinary terms used in the Old Testament for the vine and its produce, there are several others, translated with varying degrees of accuracy in the English Version; such as 'noble vine' (probably indicating one of the numerous varieties of the cultivated plant), 'tender grapes' (possibly the blossom), 'raisins,' grape-gleanings, new,' 'red,' 'strong,' sweet,' 'mixed' or 'spiced' wine, and others. Of these it is only necessary to remark, that the word מִרוּשׁ (tirosh), rendered 'new' or sweet wine,' — or 'wine' only, when associated with 'corn' and 'oil,'— appears to denote the produce of the vine generally, and not chiefly the fermented juice; just as 'corn' signifies all kinds of grain, while 'oil' similarly represents the summer fruits of Palestine when the edible fruitage of the land is spoken of. The 'vinegar' of the Old Testament was either a weak wine, such as the reapers were accustomed to drink during the heat of harvest (Ruth ii. 14), or else what we designate by that term, as in Proverbs x. z6. The 'wine' provided in such enormous quantities for the Temple builders by Solomon's orders is supposed to have been of the former kind. The vinegar given to the Saviour on the cross was doubtless the 'posed,' or wine and water, commonly drunk by the Roman legionaries. In the figurative language of Scripture the vine is emblematic of the chosen people, of the blessings of the Gospel dispensation, and also of Him in whom the Church in its various members lives and grows, and of His blood shed for the ransom of mankind (Isaiah v. 7; lv. i; John xv. i; Matt. xv. 27-29). The 'treading of the winepress' is emblematic of Divine judgments (Isaiah lxiii. 2; Lam. i. 15; Rev. xiv. 19, 20). The classical allusions to the vine and its produce would fill a volume. From its original home, 'the vine,' says Professor Hoehn, 'accompanied the teeming race of Shem to the Lower Euphrates in the south-east, and to the deserts and paradises of the south-west, where we afterwards find them settled. From Syria the cultivation of the vine spread to the Lydians, Phrygians, Mysians, and other Iranian or half-Iranian nations which had in the meantime moved up from the east. Thus it entered the Greek peninsula on the north;' and by . Greek voyagers it was introduced into Italy. The second book of Virgil's Georgics supplies not a few striking illustrations of Scripture. The poet, for instance, refers to the 'innumerable' varieties of the vine; the need of constant care and attention, and of due manuring and pruning; the possibility of degeneracy into a wild condition, yielding a sorry fruit fit only for birds; the fitness of a light and chalky soil, and the suitableness of open hills for vineyard culture. 'That land,' he says which exhales thin mists and flying vapours, and absorbs and returns it at pleasure, and which clothes itself with verdant grass, will entwine joyful vines with elms, and will be rich in oil14.' He also advises the planting of vines 'in military array,' that is in regular rows at equal intervals, just as the Greeks planted the olive in Northern Palestine; both perhaps relics of the original plan adopted in Western Asia, though not followed by the Hebrews on the hills of Canaan. The vine, as above stated, appears with the date palm, fig, and pomegranate on the Assyrian monuments—one of many evidences of the fertility and industry which once prevailed beside the Tigris and Euphrates.

|

|

|

|

|

1) 'Dr. Daubeny (Ronan Husbandry) considers that but few kinds of fruit were known to the ancients. The olive and the vine are supposed to have reached Italy through Greece; and the damson was brought from Damascus, as its name implies. 2) Two years in Syria 3) Virgil, it is true, speaks of aurea mala, 'golden apples' (Eclog. iii. 71.) but also (Eclog. ii. 51) of mala (plums?) 'hoary with soft down.' The corresponding Arabic term is also somewhat general 4) The gradual disappearance of this forest of palms is thus traced by the late Rev. Edward Wilton in his valuable but little known work, The Negeb or ' South Country' of Scripture (Macmillan, 1863) :—'Dr. Robinson shows, from the evidence of Arculf, that these groves were in existence at the close of the seventh century. But they may be traced four centuries later; for Saewulf (A.D. 1102) found them still flourishing. The process of decay or destruction must have commenced soon after (not a little facilitated probably by the Crusades); for Sir John Maundeville (A.D. 1322), whose love of the marvellous would not have suffered him to be silent respecting them, if still existing, merely says of Jericho, "it is now destroyed, and is but a little village." Exactly 400 years later, Dr. Shaw (1722) tells us "there are several" palm trees at Jericho. Time and neglect, however, were slowly but surely doing their work. In 1838 Dr. Robinson found " only one solitary palm tree lingering in all the plain;" and even " of this" (writes Dr. Macgowan in 1847) " nothing remains except the mutilated trunk, stripped of its crown of leaves."' 5) The Arabs declare that the palm tree has as many uses as there are days in the year. 6) The palm appears also in the few relics of Jewish art which have been discovered in recent times. 7) 'The art of cultivating [the date-palm] was first discovered and practised, according to Ritter, by the Nabatheans of Babylonia in the plains bordering the Lower Euphrates and Tigris. In that region forests of fruit-bearing palms stretched continuously for miles; there the tree almost sufficed for the necessities of life. From this region the cultivated date-palm spread to Jericho, Phœnicia, the Ælanitic Gulf in the Red Sea, and elsewhere.' (Hehn, Wanderings of Plants and Animals, p. 203.) The palm appears on the Assyrian monuments; and, according to Strabo, was the chief timber tree of Babylonia (Rawlinson). 8) Sat. lib. i. 8. 9) Georg. lib. i. 187-192 10) Columella, lib. iv 11) Virg. Georg. lib. ii. 179-181, 420; Columella, lib. iv. 12) Schouw, Earth, Plants, and Man. 13) Bible Plants. 14) Georg. lib. ii. 184-193, 217-221, 259-289, &c.

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD