By-Paths of Bible Knowledge

Book # 14 - Modern Discoveries on the Site of Ancient Ephesus

J. T. Wood, F. S. A.

Chapter 5

|

DESCRIPTION OF THE ORIGINAL TEMPLE OF DIANA. THE platform on which the temple was raised, called by Pliny universum templum, was 239 feet 4½ inches in width, measured on the lowest step. The exact length cannot be given for want of sufficient data, but if the distance from the lowest step to the portico at the west end is the same as it has been ascertained to be at the east end and on the north and south sides, the length was 418 feet 1½ inches. If, however, there was a wider space at the west end, as I now believe there was, to allow of a larger area for the gathering together of worshippers, and for the altars which probably stood there, it is possible that Pliny’s dimension of 425 feet was correct, although his dimension of the width is quite irreconcilable in any reasonable manner with the facts now ascertained. There was a flight of ten steps, as described by Philo, up to the pavement. of the platform; and these steps were 19 inches wide, and barely 8 inches high. Three more steps, 11 inches high, led up to the pavement of the peristyle, which was probably on the same level as

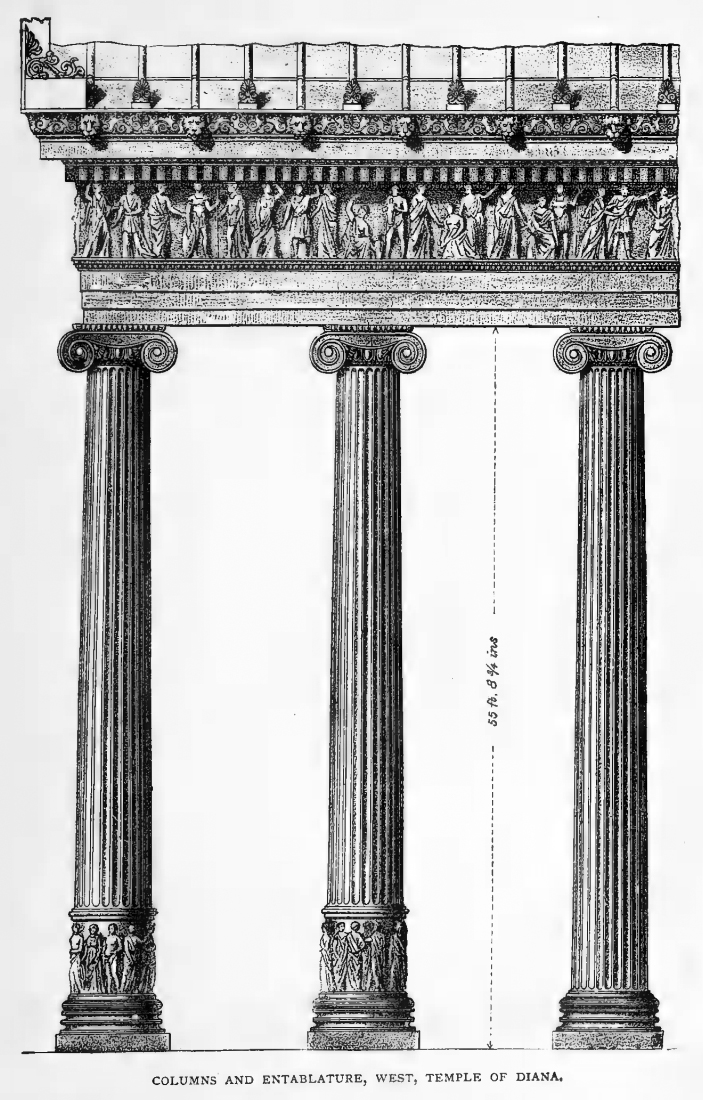

that of the pronaos. Then there were probably three more steps at the door — of these we have no data. We have here, therefore, what was most probable, a temple with its ordinary three deep steps, raised upon a platform approached by ten steps. The temple itself was 163 feet 9½ inches in width from face to face of columns, and 342 feet 6½ inches in length. It was octostyle, having eight columns in front, as described by Vitruvius, and dipteral, having two ranks of fluted columns in the peristyle. These columns were 100 in number, 6 feet 0½ inch in diameter, and 55 feet 82 inches high, including the base. The latter dimension is computed from the description of Vitruvius, that the improved Ionic Order was employed, viz. eight and a half diameters in height exclusive of the base. This accords near enough with Pliny’s dimension for the height of the columns, viz. 60 Roman feet. The Roman foot was about one-third of an inch shorter than the English foot. Pliny describes thirty-six of the hundred columns as cœlatœ (sculptured), and I have no doubt they occupied the positions shown on my plan of the temple, viz. eighteen at each extremity, as I found remains of them at the east end as well as at the west end. The data at present in our possession do not enable me to state with certainty to what height the sculpture of these columnœ cœlatœ was carried up. A medal of Hadrian distinctly represents one tier of figures only, with a band of mouldings above it. The medal of Gordianus II, published in Professor T. L. Donaldson’s Architectura Numismatica, gives a similar representation, but the band of moulding is much higher up the shaft of the column. Of the five examples of these sculptured columns now in our possession, the diameter of three of the frusta or ‘drums’ can be clearly ascertained. Of these three, two measure the same at

the base as the lowest drums of the fluted columns, viz. 6 feet 0½ inch, the third measures only 5 feet 6½ inches in the upper diameter. This would make it appear that the sculpture was carried up to the height of about 20 feet, probably for three tiers of sculpture, divided by bands of mouldings. I am very much inclined to think that the sculpture was carried up to the height named; for in addition to the fact of the much smaller diameter of one of the drums, the term columnœ

cœlatœ would not so well apply to columns having sculpture at their base only. Above the sculpture, to whatever height it was carried, the columns were no doubt fluted. Some fragments of dedicatory inscriptions, deeply incised, were found on the torus moulding of the base of one or two of the outer columns of the peristyle on the north side, and one of these shows that that particular column was the gift of a woman of Sardis- The whole of the columns were probably the gifts of either kings, communities, or individuals. The twenty-seven columns, gifts of kings or royal personages mentioned by Pliny, were in all likelihood sculptured. The intercolumniations (dimension from centre to centre of columns) were on the flanks of the temple 17 feet 1% inches, excepting the two outer intercolumniations at each extremity, where they were increased to 19 feet 4 inches, to allow, I suppose, for the projection of the sculpture on the columns, which in one of the examples found was as much as thirteen inches. The spacing of the columns in front deserves particular attention. Vitruvius, in his book dedicated to Augustus, describes the intercolumniations in front of a temple as equal, excepting only the central one, which was much wider than the others, to allow the statue within the temple to be seen from the road through the open door. But I found that there was in the temple of Diana a beautifully harmonious gradual diminution of the inter-columnar spacing from the central to the outer one, which made the extra width of the central intercolumniation quite unobjectionable. I believe Mr. Dennis found a similar arrangement at the temple of Cybele at Sardis. The dimensions are respectively — 27 feet 8½ inches, 23 feet 6 inches, 20 feet 4½ inches, and 19g feet 4 inches, the latter dimension. corresponding with the two outer intercolumniations on the flanks. The outer ordinary columns of the peristyle had twenty-four elliptical flutings 8½ inches wide at the lower diameter, and intermediate fillets one inch wide. The inner columns of the peristyle had twenty-eight elliptical flutings with fillets barely one inch wide. Vitruvius describes the inner columns of the peristyles of temples as having ‘thirty’ flutings. To beautify the exterior of the temple, statues on pedestals were probably placed between the columns and against the walls of the cella. The cella or naos of the temple was 70 feet wide, and it was doubtless hypæthral or open to the sky. There are several theories in these days as to what the hypethron of the Greeks really was; but I have taken the word in its literal sense — ‘under the sky, and I suppose that it must have been an opening in the roof, like the circular opening in the roof of the Pantheon at Rome, but in this case rectangular and oblong; and the goddess, as the Greeks believed hovering in the air above the temple, would enjoy the sweet savour of the burning offering; see Leviticus ix, The foundations for the altar, 20 feet square, found in situ, were sufficient for the statue of the goddess also; and I presume the statue stood immediately behind the altar. The statue of the goddess, which was said to have ‘fallen from Jupiter’ (Acts xix.), was probably a large aerolite, such as are found in Norway, and which, shaped by a sculptor of the day, might have been pieced out and made to assume a form similar to the well-known statues in the Museo Reale at Naples and at the Museum at Monreale near Palermo. The works of Phidias and Praxiteles with which the altar was said to abound, in addition to decorating the altar itself, probably enriched a recessed space be-. hind the altar, which was capable of displaying a number of statues on pedestals as well as bas-reliefs on the walls. The roof was covered with large white marble tiles, of which many fragments were found, as well as of the circular cover tiles. Unfortunately, the size of the flat tiles can only be ascertained approximately, by the probable distance apart of the lions’ heads in the cymatium; if I am correct in this, they were about 4 feet wide, the circular, or rather elliptical, tiles covering the joints were faced with an imbrex or antifixa 10½ inches wide. Such then was the famous building which ranked as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. The excavations brought to light the fact that its dimensions were not so enormous as they had been believed to be. Pliny’s term, universum templum, had misled everyone; instead of its applying to the temple itself, it was intended to apply to the platform upon which it was raised. Here, therefore, was a great disappointment. There is much reason for congratulation in even the scanty remains which have been secured. The main problem is now solved, the actual size of the building has been ascertained, and the style of adornment by sculpture is no longer a secret. We know now from numerous fragments that colour was extensively used

as well as gold, and although it is not in our power in the present day to appreciate the beauty of a painted building, as we do not understand the use of colour in a building like the temple, we must take it for granted that a building of exquisite beauty and proportion was the result of the united efforts of architect, sculptor, and painter. In its details, the refined conic section, the ellipse, was used for the flutings and mouldings. The earliest of the three temples of which remains were found was commenced B.C. 480 by Ctesiphon and his son Metagenes, and completed by Demetrius, a priest of Diana, and Pzonius an Ephesian. This temple was destroyed early in the fifth century B.C., and was succeeded by another built on the same site. The architect's name has not been handed down to us, but we know that it was destroyed by Erostratus on the day Alexander was born, B.C. 356. The third and last temple, which was building in the time of Alexander, and which must have made great progress at the time he visited Ephesus, as he offered to pay all the expenses of its completion, if he were allowed to dedicate the temple to Artemis in his own name; this the enthusiastic Ephesians would not allow. The architect of the temple was Dinocrates, a Macedonian. It has been suggested that the marble with which the temple was built came from the quarries in Mount Coressus; but there is no marble there, nor is there in the immediate neighbourhood of the temple any trace of a large marble quarry, such as would have furnished the material of which the temple was built. I believe myself that the marble came from Cosbounar, where there is a very large quarry of marble similar to that of which the temple was built. This quarry is between five and six miles from the temple, and if we read passuum for pedum in the description of the temple by Vitruvius, 5,000 double paces of 5 feet would extend to about the same distance.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD