By-Paths of Bible Knowledge

Book # 14 - Modern Discoveries on the Site of Ancient Ephesus

J. T. Wood, F. S. A.

Chapter 4

|

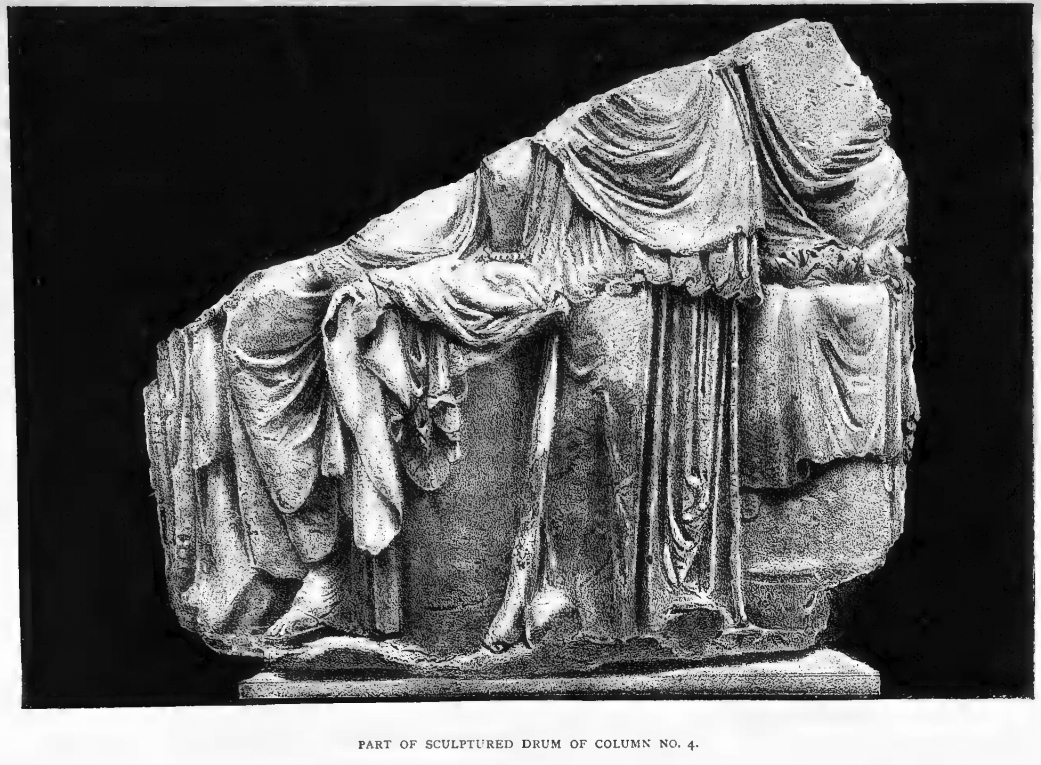

EXPLORATION OF THE SITE OF THE TEMPLE. HAVING discovered the whereabouts of the temple, I returned to England to recruit my strength and to report my success personally to the Trustees. They did not now hesitate to vote me another grant to perfect the discovery; and I returned to my work in September, 1869, with sufficient funds to proceed with the excavations, now confined entirely to the area so far marked out by the peribolus wall. I sank trial-holes in great numbers from twelve to twenty feet deep, and at the same time continued to follow the peribolus wall until a very large area was defined as including the site of the temple and its adjuncts. At a distance of some hundred yards from the angle first found, I struck upon a building which proved to be seven hundred feet long, running from west to east, in which I found at the depth of two feet a beautiful Roman mosaic pavement of a Triton, who is represented carrying in one hand a dish of fruit, in the other the pedum, or crooked stick, with which he had obtained the fruit. A dolphin carries his trident in his mouth; a large dragon-fly threatens to attack the fruit, but the Triton is guarding it with a watchful eye. Two small fish, which I suppose might even now be found in the Cayster, complete the group. The whole is surrounded by a guilloche border. This mosaic is now in the British Museum. From the position and character of the building in which this mosaic was found, I concluded that I was now not far from the site of the temple, and I sunk a great number of trial-holes to the south and east of it. The ground naturally sloped downward towards the sea, and therefore my trial-holes were necessarily deeper as I worked on eastwards, till, at a depth of nearly twenty feet, I at length found the Greek pavement I had been searching for. It consisted of two layers, the upper one nine inches thick of white marble, the lower one of rough stone fifteen inches thick; upon the small patch first found rested two fragments of one of the large sculptured columns. This discovery was made on December 31, 1869. As the next day happened to be the first of the feast of Bairam, I had the greatest difficulty in persuading the man who struck upon the pavement to remain on that day for a few hours in the morning; but he uncovered sufficient to convince me that I had really found the site of the temple, and it was thankfully welcomed by me as an acceptable New Year’s gift. It was now in my power to concentrate my force upon the opening up of the whole site. In due time, interesting portions of the temple came in view; one of the first being the remains of the anta at the south-west angle of the temple, some portions of the cella walls, and by a happy chance the foundation and base of one of the outer columns of the peristyle on the south side, and a great number of drums of columns. After I had been at work a few months, and had laid bare a considerable area down to the pavement of the earliest temple, Dr. Henry Schliemann paid me a visit. I was one day superintending the works and standing on the pavement, when I saw an active figure moving rapidly along the edge of the excavations towards the sloping road leading down to the bottom of the excavations, and in a few seconds I found myself face to face with an intelligent man of middle size, who introduced himself to me as Dr. Schliemann. Looking around him, he exclaimed in excited tones, ‘So this is the veritable pavement of the temple of Diana? Let me shake hands with you, Mr. Wood; you have immortalized yourself.’ Dr. Schliemann then confided to me his great project. He said he had studied Homer, and he was inspired with the wish to find Troy, and he felt convinced he could find it. He asked me if I thought the Turks would give him leave to go to work. I told him of the manifesto which had then been recently issued by the Sublime Porte, declaring that no more firmans for excavations would be granted. ‘But,’ said Dr. Schliemann, ‘I should not want to keep anything I found, I would give all to the Turks; I can afford to spend out of my income £1,500 a year. I then expressed my opinion that on those conditions he would not be refused a firman. The results of Schliemann’s work, and his indomitable perseverance and wonderful success, are well known. Towards the end of October, 1870, I met with a severe accident to my foot, which prevented my getting about as usual. Mrs. Wood therefore accompanied me to Ephesus, and for some days visited the works, and reported to me all that was going on. From that time to the day when the works were suspended in 1874 she went out with me to Ephesus, and stayed throughout the week. On Saturday we went down to Smyrna, where we spent Sunday, and we returned on Monday to Ephesus. As the works proceeded important remains of the temple were found, including several of the magnificent capitals of the columns of the peristyle, and several fragments of the earliest of the three temples, of which remains were eventually found, more than one fragment showing that sculptured columns were used in the earliest of these three temples. Many of the fragments found had remains of colour upon them, blue, red, and yellow. Blue formed the ground, red delineated the outline of the enrichment, and yellow covered the broad surfaces of the enrichment. By the month of March, 1871, I had laid bare a considerable part of the pavement of the temple, and the land-owners came to me for compensation. By the terms of my firman, I was obliged to obtain leave from the land-owners to dig on their land. With the assistance of Mr. Xenophon Alexarchi, our Consul at Scala Nova, I managed to arrange this weighty matter of purchase in the course of two days, seven hours each day being spent at the Konak; and I came away the happy possessor of eight acres of land at Ephesus, which comprised the site of the temple, and a considerable amount of land on the south and east sides of it. The cost was little more than £160. I had been authorized to give £200 if necessary. The land was purchased in good time, for not long afterwards a hoard of 2,600 coins was found on the site, only five feet below the present surface of the ground. These coins were chiefly of the fourteenth century, and were of Naples, Rhodes, the Seljuk Emeers, Venice, Genoa, and the Papal States. Perhaps the most interesting of these coins are those struck at Ayasalouk, bearing as they do the word ‘Theologos, which was the medieval name for Ayasalouk, and going far to prove that St. John’s Church was erected at that place. Some of the foundation-piers of a church, or some other important building, were found within the walls of the cella of the temple on the north side. Towards the east end of the site we discovered the foundations and base of a large monument only eight feet below the present surface. A large Roman sarcophagus and one or two graves were also laid bare near this spot, showing that some centuries after the destruction of the temple, and when the site was silted up to the height of fourteen feet, a Roman cemetery occupied the site. The season 1870-71 closed on May 10. An area of about 110 feet by 130 feet had been explored to as great a depth as the water standing in the excavations would allow. The heavy rains had been very unfavourable to the excavations. Early in the year 1871 the water stood so high that it was impossible to dig to a greater depth than fifteen feet below the surface, whereas most of the marble débris of the temple was found at an average depth of twenty-two feet. The latter months of the season were therefore employed in digging as deep as possible over a large area, ready for full exploration. to the level of the pavement in the autumn, by which time the water would subside. With the discovery of the base of a column in situ, the masonry supporting the steps, together with the foundation-piers and walls, which gave me the intercolumniations on the south flank, the remains of the anta in the south-west angle, and some minor discoveries, I was obliged to content myself as the result of the season’s operations; and I closed the doors of my magazines and suspended the works on the day I have above named. My grant from the Trustees had enabled me to employ on an average about one hundred workmen; and the excavations, which had been carried on entirely on the site of the temple during the past season, had made fair progress in spite of the many difficulties attending the work. I resumed actual work on September 5, 1870, with as many men as I could get together. Thistles and other self-asserting wild vegetation covered the site, and I was disappointed to find water still standing in the excavations to the depth of several feet. On September 14 was found a large block of white marble sculptured on two faces: a female is represented struggling with Hercules. My opinion is that the ninth labour of Hercules is here represented — Hercules taking the girdle of Hippolyte, the Queen of the Amazons. This block is six feet high, and is terminated by part of a rich bed mould. It is an angle stone, and I have thought, from the character of the stone and the position in which it was found, that it was an angle stone of the sculptured frieze of the temple, or that it might have been part of a- large external altar, of which there were probably several in the west front. On September 19 a still more important discovery was made. This was a large drum of one of the thirty-six sculptured columns described by Pliny as columnœ cœlatœ. The position in which this was found proved that it was part of one of the sculptured columns of the west front, which was, like the other columns, six feet and half an inch in diameter. It had fallen upon its side, and the side which lay uppermost was to a great extent chopped away, but on raising it on end the remains of five life-size figures were seen. Until this immense block, six feet high, and more than six feet in diameter, was raised to the surface, I had an anxious time of it. For any mischievously disposed person might have chopped all the sculptures off in the course of a single night. It took fifteen men fifteen days to raise it up to the surface, and I put it at once into a temporary wooden case, to protect it from injury. The principal figure represented on this drum is Hermes, with the caduceus in his right hand, the petasus hanging from his neck behind, and the chlamys twisted round his left arm. He stands nearly erect and looks upward, as if awaiting a message from Zeus. Thanatos, a nude figure, is the next most perfect figure, with large wings closed, and with sheathed sword, but with a melancholy face. An erect female figure, headless and otherwise much damaged, is supposed to represent a goddess, possibly Thetis. The remains of two seated female figures, also headless and much damaged, might have represented two other goddesses, but as the heads and upper parts of the figures are hacked away no one can say whom they represented. This beautiful unique block of marble now forms the central object in the Ephesian Gallery of the British Museum. Pliny tells us that Scopas, the famous sculptor in the time of Alexander, was employed on the sculpture of the temple; this drum of a column was probably carved from his design and under his direction, and possibly his hand had given some of its finishing touches. It will be remarked by those who look carefully at objects of art how cleverly these figures in low relief are arranged round the column, and how exquisite is the grace of the figure of Hermes. They will also observe the manner in which the feet of this figure are made to combine with the lower part of the column. As the excavations proceeded, fresh light from time to time was thrown upon what had taken place on the site of the temple, from the early time when the lowest pavement was laid, up to the time of the Turkish occupation. Sometimes a whole fortnight elapsed, with more than 300 men at work, without a ‘single discovery of consequence taking place. This was of course disheartening, but in excavating there is something of the nature of speculation, and hope was kept alive by the reflection that of such a vast building much must remain of great value. The pavement of the peristyle of the last temple was seven feet five and half inches above that of the earliest temple. The pavement of the second temple was three feet eleven and a quarter inches above that of the first. A small portion of the cella wall of the earliest temple was found undisturbed on the south flank and at the west end of the naos. This wall, six feet three inches thick, had served, with the aid of large rough blocks of stone, as the foundations of the last two temples. Another important discovery was made as the works proceeded. A great number of the rough piers and walling which had supported the steps on the north side, and a few piers and walling on the south side, were laid bare, the marble Roman pavement beyond the lower step of the stylobate or platform on which the temple was raised, and a considerable length of the step itself in situ. The water subsided in the excavations before the close of the year 1871, and I was able to remove the six feet of débris, and to recover a great number of fragments of the temple. A great number of fragments of the bead and red enrichment of various sizes, with remains of colour upon many of them, gave evidence of the delicacy of the architectural carving. All the angles were acute, so that the arrises were as sharp as a knife, and the very hard nature of the marble used facilitated this kind of workmanship. This marble is unmarketable in England from its hardness. In the mouldings and the flutings of the columns the ellipse was used, as usual with the ancient Greeks; the fillets dividing the flutings were narrow, being no more than one inch. The flutings at the base of the shaft were eight and a quarter inches wide. Altogether the remains of five of the sculptured drums of columns were found, three at the west end and two at the east end. This goes far to prove that there were eighteen at each end, making the thirty-six columnœ cœlatœ mentioned by Pliny. The difference of style of the design and carving of the figures of these sculptured columns is most conspicuous, The large drum at the west end and that at the east end had each ten figures in their circumference, and the relief was very low — only four inches. The half drum found at the west end — of which remain only two figures in very high relief — is of smaller diameter, and could not have had more than five figures on its circumference. The smaller diameter — five feet six and a half inches — favours my opinion that these columns were sculptured to the height of nearly twenty feet, and with three tiers of subjects, — divided by bands of mouldings. A further proof that this was the case is the term used by Pliny in describing them, columnœ cœlatœ. Sculptured columns could hardly be applied to columns sculptured for only six feet in height. One of the drums found at the east end was also of smaller diameter. I cannot with certainty say how many figures were carved upon it, perhaps six or seven. This drum had quite a distinct architectonic character; the figures upon it were alternately sitting and standing, and the stools upon which the figures were seated were designed to mark plainly the circumference of the column. The other drum at the east end, which had ten figures, is so much hacked that little remains of the figures but drapery; the heads in all cases are missing. The fragment of the fifth sculptured drum, found at the west end, is so small that nothing more can be said of it but that the Persian trouser is conspicuous in it. I now found part of the base and foundation of one of the inner columns of the peristyle on the north side. Both this column, and the one on the south side of which the base was found, had evidently been allowed to remain standing for some time after the destruction of the temple, as the drums of these columns were found on the surface of about six feet of silt. I removed the stones composing the base of the southern column, and

these are re-erected in the British Museum, with a portion of the fluted shaft belonging to it. Now that these important remains had come to light, the Turks began to understand to a certain extent the object of the excavations. On February 10, I reported to the Trustees that I had cleared out 38,500 cubic yards from the site of the temple, at a total cost of about £4,000. This was about one third of the work required to be done to clear out the whole of the temple site. An average of about 150 men were employed on the excavations in the course of this season, my grant being limited to a fixed amount, which did not admit of the employment of a greater number. Although by March, 1872, I had been greatly disappointed to find that the early Christians had done their best to destroy every vestige of the temple, I had found sufficient to encourage the hope that the Trustees would apply to the Treasury for another grant to continue the excavations. I estimated that £6,000 would be needed to clear out the whole of the site of the temple, and to a certain distance beyond it. As it was doubtful whether my firman would be renewed, I was ordered to suspend the works at the end of April, or until the firman was renewed. As the excavations proceeded we re-opened many deep holes which I had sunk on the site of the temple several years before its discovery. These happened to be in places where no remains were discovered to indicate the site, and they had been refilled, according to the conditions of my firman, in order that the land might be cultivated. On resuming work in September, 1872, near the western extremity on the north side of the pronaos of the temple, we soon found two large sculptured blocks which might have been the angle and adjoining block of the frieze at the north-west angle, or part of a large altar. Portions of two life-size male figures are carved on one face, and the lifting of Anteus by Hercules seems to be here represented. On the return side of the angle-block there had evidently been a female figure (perhaps Artemis _ herself) and a deer, of which little remains but the head and antlers. The Goths are credited with the partial destruction of the last temple, A.D. 260; and some twenty years later the early Christians accomplished its total destruction. After which, at a period unknown, but probably near the close of the third century A.D., they determined to build a church within the cella walls, which had been allowed to remain standing for some feet above the pavement of the earliest temple. The early Christians, before removing what at that time was left standing of the cella walls, built against them massive piers of rubble masonry; when they had proceeded so far, a tremendous earthquake occurred, which, running from south-east to northwest, overthrew several of the foundation-piers, and raised part of the pavement five feet above its original level, with a large mass of the mortar which had been mixed upon it. It was quite evident that they then abandoned the idea of building a church within the cella walls; they therefore proceeded to remove them, and as the piers had been built with large quantities of mortar, the impression of every stone, with its marginal draft and bevilled edge, remained on the piers, and could be easily discerned when the excavations laid them bare. A few cut stones were found on the site, which had not been used, and were evidently prepared to be put in their respective places in the superstructure as soon as the building was ready for them. Within the cella was found an elliptical Corinthian capital, which I presume had been used in the upper tier of columns decorating the cella in the time of Marcus Aurelius, when probably great alterations were made in the interior. This emperor’s name, with that of his wife Faustina and his daughter Fadilla, were found carved in large characters on the lintel of the door at the west end.; Near the west door were found two large blocks of marble, with circular grooves eight inches wide and three and a quarter inches deep; these were doubtless the blocks on which the door turned inward on bronze wheels. Mortice holes for the door-frame were sunk in these blocks. The exact width of the whole door was now ascertained to have been fourteen feet eight and a half inches, in two parts, and they were probably thirty-five feet high. Judging from the present position of these blocks, they must have belonged to one of the last two temples, most probably the last but one. Grooved blocks similar to those here described are to be seen at the Parthenon at Athens and other Greek temples. By the end of the year 1872, I had removed 70,126 cubic yards from the site of the temple. Early in the month of January, 1873, the water in the excavations had sunk sufficiently to allow us to lay bare large patches of the pavement beyond the steps of the platform, and ten feet lower than the Greek pavement already described. This pavement was Roman; it consisted of large square slabs of white marble three inches thick, laid upon a foundation composed of red cement three inches thick and rubble masonry twenty-one inches thick. This pavement was probably laid down not long before the destruction of the last temple, as it did not show much wear. I now began to clear away the soil and débris for the distance of thirty feet beyond the lowest step of the platform, where I hoped to find many remains; but I was disappointed, for here was found scarcely a vestige of the building remaining. Much sickness now prevailed among the men; I preserved my own health by good food, and moderate exercise taken on foot and on horseback. With my horse I was able to explore by degrees the whole plain, without absenting myself for any length of time from the works. The substructures of the ruins of the city are partly inhabited by shepherds, who to each flock have four or five large dogs, which area great annoyance to travellers on horseback; and the only way to rid oneself of them is to dismount and throw stones at them: one dog is sure to be hit, and he runs away howling, followed by the others in sympathy. The dogs of the Yourooks (a wandering tribe) are also troublesome; but these people are generally at hand, and call off the dogs. One evening I was returning with some ladies from an expedition to the sea-side, and on our way we passed near the black tents of the Yourooks in the forum, and were admiring the scenery, when a fierce dog rushed forward to attack us; his young mistress, however, called him away; he at once returned to her side, and she put her foot upon his back to prevent his annoying us. She was a beautiful girl, and as she stood with her foot upon the dog’s back, her hands busily employed in knitting, her dress of many bright colours, the whole group stood out against the black tent, and with it formed a picturesque foreground against the landscape, which in its turn was backed by the steeps of Mount Prion. In January, 1873, I obtained those particulars which I had sought for to confirm the statement of Vitruvius that the temple was octostyle. In an upper stratum of the excavations was found a curious bas-relief in three panels, representing a three days’ contest between a man (a Christian perhaps) and a lion. The first and uppermost panel is so far destroyed that the result of the contest is unknown. In the second panel the man appears armed with a thick club, from which the lion receives a blow on the head which probably stuns him, and thus ends the second day. On the third and last day the man falls a victim to the lion’s fury; he is on the ground, and the lion tears out his bowels. During the month of February, 1873, the men were chiefly employed at the east end of the temple, and here another sculptured drum was found. The works were stopped altogether for a few days this month by the intense cold. A sharp frost, a cold wind, and rain, however slight, were each sufficient to suspend work. Very few of the men had a change of clothes, so they generally ran for shelter en masse when rain came on, often not waiting for paidos to be called. Some of my Turkish workmen were particularly adroit in throwing up the sand out of the excavations; in digging the trial-holes they would throw a good shovelful of sand and stones out of a hole twelve feet deep. They were very strong, although their food was of the simplest kind. Coarse bread and a little salt fish or olives, black raisins, and some fruit, such as an orange or an apple occasionally, washed down by copious draughts of the best water they could obtain, constituted their breakfast at eight and their dinner at one o’clock. To their supper, being their most sumptuous meal, were sometimes added snail soup, thistle broth, boiled thistle stalks, dandelion, and other wild vegetables. With this frugal diet their strength was surprising, as proved by the fatigue they endured, notwithstanding the unhealthiness of the climate, and the great weights which they raised in their arms or carried on their backs. The Turkish porters in Smyrna, who also live most frugally, often carry from 400 to 600 pounds weight on their backs; and a merchant one day pointed out to me one of his men who had carried an enormous bale of merchandise, weighing 800 pounds, up a steep incline into an upper warehouse. In 1873 I was detained in England later than usual because the Turkish authorities hesitated to renew my firman; it was at length renewed for another year, on condition that no more firmans should be asked for, and on September 15 I received marching orders. On September 19 we left England, and arrived in Smyrna, October 3, having been detained by unusually tempestuous weather and a cyclone in the Straits of Messina, and having been obliged to avoid Marseilles by fear of quarantine at the end of our voyage. On October 6 we went out to Ephesus, and a long stretch of more than 100 feet of the lowest step of the platform was now discovered on the north side. This was one of the ten steps described by Philo on which the temple was raised; it was barely eight inches high. A space of six feet leading to this step was found in situ at the east end. Built upon the step and the masonry adjoining it, we found a circular lime-kiln fifteen feet in diameter, with some lime still remaining in it. Near the lime-kiln was found an immense heap of small marble chippings standing ready to be thrown into the kiln,, which had doubtless already swallowed up most of the sculpture of the temple which remained at that time. I have no doubt that this was also the work of the early Christians, who were stopped in their work of building by the earthquake I have already mentioned. The chippings were carefully examined, but very few and very small fragments of sculpture were found in the whole heap. In October, amongst other fragments of the temple, was found a large fragment of what was probably part of the large central acroterion of the west pediment. Two more sculptured blocks, similar to those I have supposed might have been either portions of the frieze or of a large external altar, were found in November. A long oak beam much charred was found on the pavement on the north side; this was probably from the roof. While the excavations were going on we had many visitors, who wished to carry away with them a morsel of the temple as a memento of their visit; and I was often very much perplexed when a visitor, generally a lady, would take up a fragment of enrichment from the temple, and ask leave to take it away with her. It was very disagreeable to refuse, so I hit upon a plan which met the difficulty admirably. In some of the upper strata, and indeed in the lowest stratum of the excavations, were found an immense number of Roman enriched fragments; these I ordered to be carried up to the top, and they made a large heap, to which I in future referred those of my visitors who wanted a fragment. I was fortunately never asked what they were, or whether they came from the temple; and they were delighted with the nice little bits they found in the heap. One fragment from the temple found about this time was of special interest; it consisted of two astragals (small round mouldings) between which was doubled a narrow strip of thin lead, a strip of gold being inserted in the fold of the lead. Part of the gold had been torn away, but I suppose that originally it turned down and formed a narrow fillet between the astragals. This was the only specimen of the kind found in the whole course of the excavations; but I suppose that a great quantity of gold was used in this manner, and it must have contributed much to the beauty of the temple. This discovery confirms in a measure the statement of Pliny that at Cyzicus there was a delubrum, or small temple, in which there was a thread or strip (filum) of gold in every joint of the marble; and in the inscription giving the accounts for the building of the Erectheum there is an item of so much gold-leaf purchased for gilding certain ornaments. Several fragments of sculpture, including part of a female arm, and another with the elbow, both from figures about eleven feet high, were found at the west end of the temple, and had probably formed part of the sculpture in the tympanum of the pediment at that end; the toe of a colossal figure was found at the east end, and was probably from the pediment at that end. A large plain block of marble from the pediment shows that the angle of the roof was 17°. A fragment of the lowest step of the platform was now found at the east end; this was a most important discovery, as it fixes the limit of the temple at that end, although it may not give the length of the platform with certainty, as no part of the step was found at the west end, and Pliny’s dimension of 425 feet may be correct for aught I know to the contrary. The unusual dryness of the season favoured the exploration down to the level of the pavement, below which the water sank sufficiently low to enable us to rescue a great number of important architectural fragments that rested upon the Roman pavement beyond the steps. Some large lions’ heads from at least two of the three temples were found here. On close examination of the foundations of the base of the inner column on the north side, I found three of the stones of the base of the earliest temple; there was not sufficient left for me to obtain the exact diameter, but I believe the columns of that temple were of a larger diameter. I also found that the foundations of this column were placed upon a thin layer of red cement to keep the damp from rising. At the distance of thirty feet ten inches from the lowest step of the platform was found the kerb of a portico twenty-five feet two inches wide, remains of which were found on both flanks of the temple, and which probably surrounded it on all sides. And on the south side were found considerable remains of a Grecian Doric building at a little distance beyond the portico on the south side. On the pavement of the portico on the south side, I had the good fortune to find a large fragment of the cymatium of the great cornice of the temple; this is beautifully enriched with the conventional Greek honeysuckle, in high relief. A length of nearly 350 feet of this beautiful feature, studded frequently with lions’ heads more than two feet wide, must have had a fine effect in conjunction with the remainder of the cornice. With the opening of the year 1874 came great disappointment and vexation. On January 2, Mr. Newton came to Smyrna, and even before visiting the works he expressed his opinion that they had now better be stopped, as they had not been very productive during this season, and he feared that sufficient would not be found to justify further explorations. In this view I did not concur; but he urged immediate suspension of the works; and being unable to persuade him to the contrary, they were forthwith suspended by telegram, much to the amazement and confusion of the poor workmen, who were so suddenly and prematurely discharged. The next day Mr. Newton accompanied me to Ephesus. We found about one hundred and fifty of the discharged workmen assembled on the platform of the station, awaiting our arrival, who hoped they might still be employed. A visit to the excavations did not induce Mr.. Newton to alter his opinion, so with a sore heart I paid the men and discharged all but twenty, whom I retained to go on for a while longer with the excavations at the east end of the temple, and with the further exploration of the Doric building already mentioned; the latter was done at the express wish of Mr. Newton. Of this building I can give no satisfactory account, as my means would not permit sufficient exploration. I had now only the amount (about £200) to spend which the sale of my plant might realise. At the east end of the temple we found an ancient well; this we carefully cleared out. Sometimes treasure is found in wells, but in this case we only found a little valueless pottery, sand, and stones. On the north side of the temple, we found a beautiful cameo of a winged figure. As the water in the excavations now stood at a remarkably low level, we were able to clear out the cella, where we found a number of fragments of some interest — these were part of an enriched Roman frieze — a fine lion’s head, part of a statue belonging probably to one of the earliest temples, as it was of a decidedly archaic character; also some fragments of sculpture and architectural enrichment below the level of the pavement. A great number of fragments, large and small, of the marble tiles of the roof were found scattered all over the pavement. Bearing in mind Pliny’s description of the precautions taken in laying the foundations of the temple to prevent the damp rising, viz. by laying a bed of charcoal, and over that placing fleeces of wool, I sunk with the aid of the pump four deep holes, one inside the cella against the west wall, one outside against the south wall, one near the centre of the cella, and one under the peristyle at some distance from the cella wall on the north side. In the holes sunk close to the cella walls I found, at the depth of 5 feet 9 inches, a layer 4 inches thick of a composition which had the appearance and consistency of glazier’s putty; below this was a layer of charcoal 3 inches thick, and below that, another layer of the putty-like composition 4 inches thick. We made an effort to get out a cutting of the whole mass, but it was impossible, the water ran in almost as fast as we pumped it out, and I could only obtain a few small examples of the composition and charcoal. The composition was analyzed by Mr. Matthieson, and it was found to consist of carbonate of lime 6591, silica 2610, water, &c. (volatile) 455, nitrogen, a trace; so that, in point of fact, we have here nothing but a species of mortar. Below all this, I came upon the natural soil, which was alluvial, and was composed of sand and small water-worn stones of irregular form. The foundations of the walls consisted of rather small stones, and there was an offset of 3 feet on the inner side, which made the foundations very wide and substantial. In consultation with Mr. Newton, it was finally decided to take to pieces and examine the whole of the foundation piers of the church. In doing this, which was to a certain extent accomplished by the aid of gunpowder in small quantities, we found a great number of fragments of an archaic frieze which had probably belonged to the great altar of the first temple. Also many fragments of architectural enrichment, a Greek inscription, a small archaic head of very remarkable character, as it was attached to a rounded surface, and this with another fragment of the lower part of a male figure also attached to a rounded surface had most probably formed parts of a sculptured column from the earliest temple. An archaic lion’s head, probably from the second temple, which formed a gargoyle, is one of the most interesting things found in taking down these piers. A large block of sculptured marble found at the west end of the temple represented a winged male figure leading a ram. This was probably from one of the altars in front of the temple. Part of a large boar’s head found in the cella was probably of the same period as the lion’s head, which I have assigned to the last temple. The lowest marble pavement, of which quite one-half remains outside the cella walls, and which is 7 feet 6½ inches below the pavement of the peristyle of the last temple, was evidently that of the earliest temple. This pavement continued on the same level throughout the cella, and there was no step up at the door. We had most lovely weather for our work during January, which is one of the most pleasant months in the year in Asia Minor, being bright without glare. February brought cold weather, and many a day the men were unable to work. In March the cold increased, the saws which we used to saw off inscriptions were found in the morning frozen in the stones, if not removed at night, and warm water was used in working them. Ice an inch thick stood in the excavations for a whole week; for many days my men could not work. The intensity of the cold in the interior was so great that shepherds and others were found frozen to death; others were brought frost-bitten and helpless into the hospitals at Smyrna. As soon as the works could be resumed, I took on twenty more men, and with the forty men I now had I worked on till my funds were quite exhausted. On March 27 I reported to the Trustees that I had cleared out and thoroughly examined 132,220 cubic yards, nearly the whole of which had been wheeled out from the site. I had received orders to sell my plant and suspend operations. My carts and horses were bought by Mr. De Cuyper, a gentleman who was engaged in mining operations: with the horses my faithful Nubian groom Billal must go; he was most unwilling to go before we left, but stern necessity obliged him to yield, and the poor man, who had served me faithfully for eight years, wept bitterly when he came to say good-bye, his heart having been touched by the kindness of his mistress. Mr. De Cuyper also engaged about a dozen of my workmen; these men had been with me for years, and they would not be persuaded to leave before we left, although they thus sacrificed five or six days’ wages; they said they could not go, they had their clothes to wash. So there are a few men even among the ‘unspeakable’ Turks who have kind and impressible hearts, and here is a small tribute to their honour. On March 25 the works were finally suspended, much to my regret, as I feel sure we have left much of interest and value behind us beyond the margin of the present excavations. Notwithstanding the comparatively barren results of the season 1873-74, I had twenty-three cases and sixty-three blocks of marble ready to send home. As there was no ship-of-war bound for either Malta or England, this last batch of antiquities was put on board a merchant vessel bound for England. Admiral Randolph, who happened to be with his ship in the port of Smyrna, kindly assisted me in this by the supply of men, boats, and tackle. Having seen this done we left for England, viâ Constantinople, on board H,B.M.’s ship Cockatrice. It will readily be believed that we did not leave either Smyrna or Ephesus without heartfelt regret, after so many years’ sojourn. As we left Ephesus, feeling it was probably for ever, we looked back frequently at the beautiful scene which had had such a fascination for us, and which had been for so many years associated with our united labours. My wife’s best exertions had been used in doing all she could to alleviate the sufferings of the workmen and villagers, and her skill and care were proved by the fact that of hundreds of workmen only two or three were obliged to be sent down to Smyrna to be treated in the hospitals by skilled doctors. The workmen and villagers, though they anxiously sought Mrs. Wood’s aid, stood modestly waiting by the wayside as she passed between our home and the works. As for me, the task I had set myself had been accomplished. The situation, plan, and particular characteristics of the long-lost temple had been discovered, and all that remained of it within the area explored had been secured for our national collection of antiquities. At Smyrna, where for so many years we had experienced so much kindness, we parted from our friends with deep regret; cheered, however, by the hope that we should one day return and see them all again, and perhaps renew the work so abruptly stopped: for had we not drunk freely of the Fasoolah water1? The whole cost of the excavations at Ephesus from 1863 to 1874 was £16,000 — £12,000 of which amount were spent on clearing out the temple site.

|

|

|

|

|

1) They say in Smyrna that all who drink of the water of this spring are sure to return to Smyrna sooner or later. The fact is that all people who have for any length of time breathed the fresh light air of Smyrna, and have found kind friends among the inhabitants, are glad to return, if only for a few days.

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD