By-Paths of Bible Knowledge

Book # 7 - Assyria - Its Princes, Priests, and People

By A. H. Sayce M.A.

Chapter 4

|

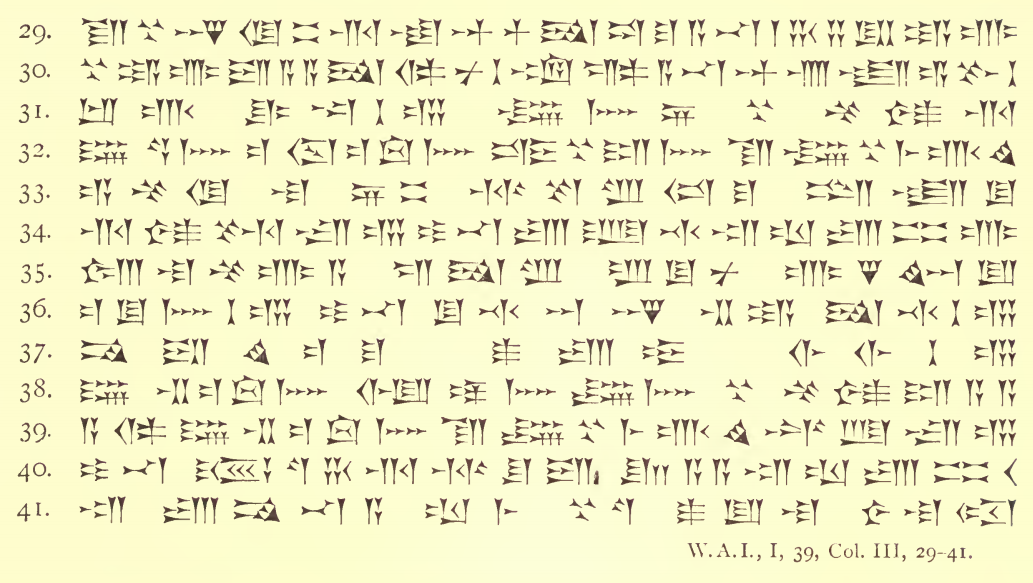

Art, Literature, and Science Assyrian art was, speaking generally, imported from Babylonia. Even the palace of the king was built of bricks, and raised upon a mound like the palaces and temples of Babylonia, although stone was plentiful in Assyria, and there was no marshy plain where inundations might be feared. It was only the walls that were lined with sculptured slabs of alabaster, the sculptures taking the place of the paintings in vermilion, which adorned the houses of Babylonia (Ezek. xxiii. 14). It is at Khorsabad, or Dur-Sargon, the city built by Sargon, to the north of Nineveh, that we can best study the architectural genius of Assyria. The city was laid out in the form of a square, and surrounded by walls forty-six feet thick and over a mile in length each way, the angles of which faced the four cardinal points. The outer wall was flanked with eight tall towers, and was erected on a mound of rubble. On the north-west side stood the royal palace, defended also by a wall of its own, and built on a T-shaped platform. It was approached through an outer court, the gates of which were hung under arches of enamelled brick, and guarded by colossal figures in stone. From the court an inclined plane led to the first terrace, occupied by a number of small rooms, in which the French excavators saw the barracks of the palace-guard. Above this terrace rose a second, at a height of about ten feet, upon which was built the royal palace itself. This was entered through a gateway, on either side of which stood the stone figure of a 'cherub,' while within it was a court 350 feet long and 170 feet wide. Beyond this court was an inner one, which formed a square of 150 feet. On its left were the royal chambers, consisting of a suite of ten rooms, and beyond them again the private chapel of the monarch, leading to the apartments in which he commonly lived. On the west side of the palace rose a tower, built in stages, on the summit of which was the royal observatory. It is a question whether the Assyrian palace possessed any upper stories. On the whole, probability speaks against it. Columns, however, were used plentifully. The column, in fact, had been a Babylonian invention, and originated in the necessity of supporting buildings on wooden pillars in a country where there was no stone. From Babylonia columnar architecture passed into Assyria, where it assumed exaggerated forms, the column being sometimes made to rest on the backs of lions, dogs, and winged bulls. The apertures which served as windows were protected by heavy folds of tapestry, that kept out the heats of summer and the cold winds of winter. In warm weather, however, the inmates of the house preferred to sit in the open air, either in the airy courts upon which its chambers opened, or under the shady trees of the paradeisos or park attached to the dwellings of the rich. The leases of houses let or sold in Nineveh in the time of the Second Assyrian Empire generally make mention of the 'shrubbery,' which formed part of the property. Assyrian sculpture was for the most part in relief. The Assyrians carved badly in the round, unlike the Babylonians, some of whose sitting statues are not wanting in an air of dignity and repose. But they excelled in that kind of shallow relief of which so many examples have been brought to the British Museum. We can trace three distinct periods in the history of this form of art. The first period is that which begins, so far as we know at present, with the age of Assur-natsir-pal. It is characterised by boldness and vigour, by an absence of background or landscape, and by an almost total want of perspective. With very few exceptions, faces and figures are drawn in profile. But with all this want of skill, the work is often striking from the spirit with which it is executed, and the naturalness with which animals, more especially, are depicted. A bas-relief representing a lion-hunt of Assur-natsir-pal has been often selected as a typical, though favourable, illustration of the art of this age. The second period extends from the foundation of the Second Assyrian Empire to the reign of Esar-haddon. The artist has lost in vigour, but has compensated for it by care and accuracy. The foreground is now filled in with vegetable and other forms, all drawn with a pre-Raffaellite exactitude. The relief consequently becomes exceedingly rich, and produces the effect of embroidery in stone. It is probable that the delicate minuteness of this period of art was in great measure due to the work in ivory that had now become fashionable at Nineveh. The third, and best period, is that of the reign of Assur-bani-pal. There is a return to the freedom of the first period, but without its accompanying rudeness and want of skill. The landscape is either left bare, or indicated in outline only, the attention of the spectator being thus directed to the principal sculpture itself. The delineation of the human figure has much improved; vegetable forms have lost much of their stiffness, and we meet with several examples of successful foreshortening. Up to the last, however, the Assyrian artist succeeded but badly in human portraiture. Nothing can surpass some of his pictures of animals; when he came to deal with the human figure he expended his strength on embroidered robes and the muscles of the legs and arms. The reason of this is not difficult to discover. Unlike the Egyptian, who excelled in the delineation of the human form, he did not draw from nude models. The details of the drapery were with him of more importance than the features of the face or the posture of the limbs. We cannot expect to find portraits in the sculptures of Assyria. Little, if any, attempt is made even to distinguish the natives of different foreign countries from one another, except in the way of dress. All alike have the same features as the Assyrians themselves. The effect of the bas-reliefs was enhanced by the red, black, blue, and white colours with which they were picked out. The practice had come from Babylonia, but whereas the Babylonians delighted in brilliant colouring, their northern neighbours contented themselves with much more sober hues. It was no doubt from the populations of Mesopotamia that the Greeks first learnt to paint and tint their sculptured stone. Unfortunately it is difficult, if not impossible, to find any trace of colouring remaining in the Assyrian bas-reliefs now in Europe. When first disinterred, however, the colours were still bright in many cases, although exposure to the air soon caused them to fade and perish. The bas-reliefs and colossi were moved from the quarries out of which they had been dug, or the workshops in which they had been carved, by the help of sledges and rollers. Hundreds of captives were employed to drag the huge mass along; sometimes it was transported by water, the boat on which it lay being pulled by men on shore; sometimes it was drawn over the land by gangs of slaves, urged to their work by the rod and sword of their task-masters. On the colossus itself stood an overseer holding to his mouth what looks on the monument like a modern speaking-trumpet. Over a sculpture representing the transport of one of these colossi Sennacherib has engraved the words: 'Sennacherib, king of legions, king of Assyria, has caused the winged bull and the colossi, the divinities which were made in the land of the city of the Baladians, to be brought with joy to the palace of his lordship, which is within Nineveh.' We may infer from this epigraph that the images themselves were believed to be in some way the abode of divinity, like the Beth-els or sacred stones to which reference has been made in the last chapter. Fragment now in the British Museum showing primitive Hieroglyphics and Cuneiform Characters side by side. Like Assyrian art, Assyrian literature was for the most part derived from Babylonia. A large portion of it was translated from Accadian originals. Sometimes the original was lost or forgotten; more frequently it was re-edited from time to time with interlinear or parallel translations in Assyro-Babylonian. This was more especially the case with the sacred texts, in which the old language of Accad was itself accounted sacred, like Latin in the services of the Roman Catholic Church, or Coptic in those of the modern Egyptian Church. The Accadians had been the inventors of the hieroglyphics or pictorial characters out of which the cuneiform characters had afterwards grown. Writing begins with pictures, and the writing of the Babylonians formed no exception to the rule. The pictures were at first painted on the papyrus leaves which grew in the marshes of the Euphrates, but as time went on a new and more plentiful writing material came to be employed in the shape of clay. Clay was literally to be found under the feet of every one. All that was needed was to impress it, while still wet, with the hieroglyphic pictures, and then dry it in the sun. It is probable that the bricks used in the construction of the great buildings of Chaldea were first treated in this way. At all events we find that up to the last, the Babylonian kings stamped their names and titles in the middle of such bricks, and hundreds of them may be met with in the museums of Europe bearing the name of Nebuchadnezzar. When once the discovery was made that clay could be employed as a writing material, it was quickly turned to good account. All Babylonia began to write on tablets of clay, and though papyrus continued to be used, it was reserved for what we should now term 'ťditions de luxe.' The writing instrument had originally been the edge of a stone or a piece of stick, but these were soon superseded by a metal stylus with a square head. Under the combined influence of the clay tablet and the metal stylus, the old picture-writing began to degenerate into the cuneiform or 'wedge-shaped' characters with which the monuments of Assyria have made us familiar. It was difficult, if not impossible, any longer to draw circles and curves, and accordingly angles took the place of circles, and straight lines the place of curves. Continuous lines were equally difficult to form; it was easier to represent them by a series of indentations, each of which took a wedge-like appearance from the square head of the stylus. As soon as the exact forms of the old pictures began to be obliterated, other alterations became inevitable. The forms began to be simplified by the omission of lines or wedges which were no longer necessary, now that the character had become a mere symbol instead of a picture; and this process of simplification went on from one century to another, until in many instances the later form of a character is hardly more than a shadow of what it originally was. Education was widely spread in Babylonia; in spite of the cumbrousness and intricacy of the system of writing, there were few, it would appear, who could not read and write, and hence, as was natural, all kinds of handwritings were prevalent, some good and some bad. Among these various cursive or running hands were some which were selected for public documents; but as the hands varied, not only among individuals, but also from age to age, the official script never became fixed and permanent, but changed constantly, each change, however, bringing with it increased simplicity in the shapes of the characters, and a greater departure from the primitive hieroglyphic form. The earliest contemporaneous monuments with which we are at present acquainted, are those recently excavated by the French Consul M. de Sarzec at a place called Tel-Loh; on these we see the early pictures in the very act of passing into cuneiform characters, the pictures being sometimes preserved and sometimes already lost. A comparison of the forms found at Tel-Loh with those usually employed in the time of Nebuchadnezzar, will show at a glance what profound modifications were undergone by the cuneiform syllabary in the course of its transmission from generation to generation. In contrast to the Babylonians, the Assyrians were a nation of warriors and huntsmen, not of students, and with them, therefore, a knowledge of writing was confined to a particular class, that of the scribes. At an early period, accordingly, in the history of the kingdom, a special form of script was adopted not only in official documents, but in private documents as well, and this script remained practically unchanged down to the fall of Nineveh. This form of script was one of the many simplified forms of handwriting that were used in Babylonia, and it was fortunately a very clear and well-defined one. Now and then, it is true, contact with Babylonia made an Assyrian king desirous of imitating the archaic writing of Babylonia, and inscriptions were consequently engraved in florid characters, abounding in a multiplicity of needless wedges, and reminding us of our modern black-letter. Such ornamental inscriptions are not numerous, and were carved only on stone. The clay literature was all written in the ordinary Assyrian characters, except when the scribe was unable to recognise a character in a Babylonian text he was copying, and so reproduced it exactly in his copy. The clay tablets used by the Assyrians were an improvement on those of Babylonia. Instead of being merely dried in the sun, they were thoroughly baked in a kiln, holes being drilled through them here and there to allow the steam to escape. As a rule, therefore, the tablets of Assyria are smaller than those of Babylonia, since there was always a danger of a large tablet being broken in the fire. In consequence of the small size of the tablets, and the amount of text with which it was often necessary to cover them, the characters impressed upon them are frequently minute, so minute, indeed, as to suggest that they must have been written with the help of a magnifying glass. This supposition is confirmed by the existence of a magnifying lens of crystal discovered by Sir A. H. Layard on the site of the library of Nineveh, and now in the British Museum.

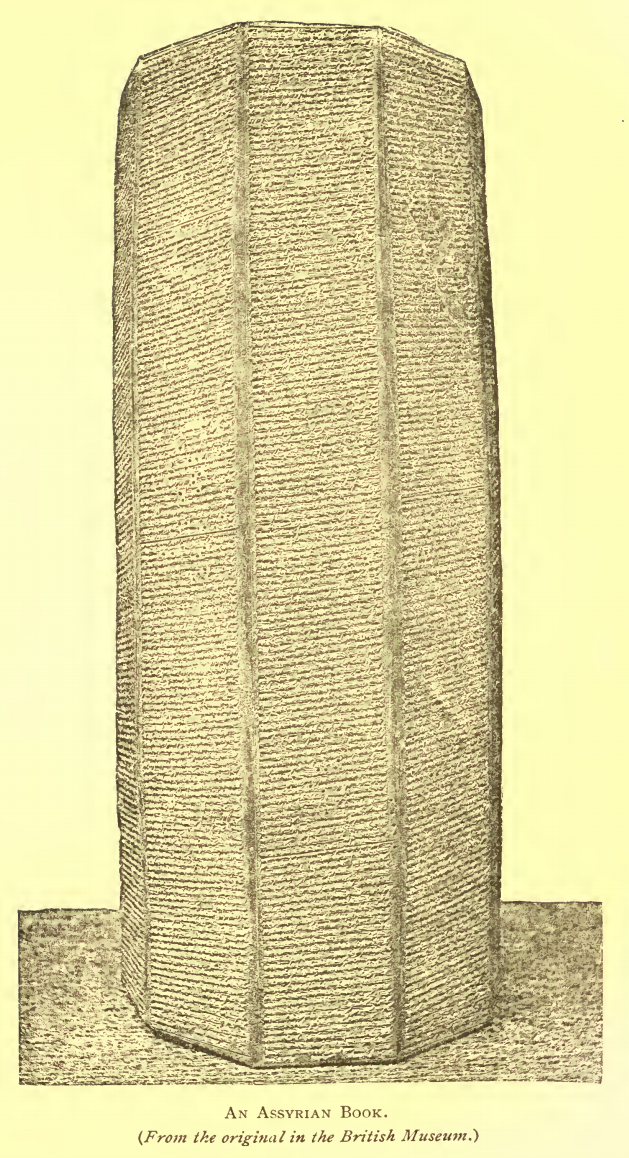

An Assyrian Book. A literary people like the Babylonians needed libraries, and libraries were accordingly established at a very early period in all the great cities of the country, and plentifully stocked with books in papyrus and clay. In imitation of these Babylonian libraries, libraries were also founded in Assyria by the Assyrian kings. There was a library at Assur, and another at Calah which seems to have been as old as the city itself. But the chief library of Assyria that, in fact, from which most of the Assyrian literature we possess has come, was the great library of Nineveh (Kouyunjik). This owed its magnitude and reputation to Assur-bani-pal, who filled it with copies of the plundered books of Babylonia. A whole army of scribes was employed in it, busily engaged in writing and editing old texts. Assur-bani-pal is never weary of telling us, in the colophon at the end of the last tablet of a series which made up a single work, that 'Nebo and Tasmit had given him broad ears and enlightened his eyes so as to see the engraved characters of the written tablets, whereof none of the kings that had gone before had seen this text, the wisdom of Nebo, all the literature of the library that exists,' so that he had 'written, engraved, and explained it on tablets, and placed it within his palace for the inspection of readers.' A good deal of the literature was of a lexical and grammatical kind, and was intended to assist the Semitic student in interpreting the old Accadian texts. Lists of characters were drawn up with their pronunciation in Accadian and the translation into Assyrian of the words represented by them. Since the Accadian pronunciation of a character was frequently the phonetic value attached to it by the Assyrians, these syllabaries, as they have been termed—in consequence of the fact that the cuneiform characters denoted syllables and not letters—have been of the greatest possible assistance in the decipherment of the inscriptions. Besides the syllabaries, the Semitic scribes compiled tables of Accadian words and grammatical forms with their Assyro-Babylonian equivalents, as well as lists of the names of animals, birds, reptiles, fish, stones, vegetables, medicines, and the like in the two languages. There are even geographical and astronomical lists, besides long lists of Assyrian synonyms and the titles of military and civil officers. Other tablets contain phrases and sentences extracted from some particular Accadian work and explained in Assyrian, while others again are exercises or reading-books intended for boys at school, who were learning the old dead language of Chaldea. In addition to these helps whole texts were provided with Assyrian translations, sometimes interlinear, sometimes placed in a parallel column on the right-hand side; so that it is not wonderful that the Assyrians now and then attempted to write in the extinct Accadian, just as we write nowadays in Latin, though in both cases, it must be confessed, not always with success. Accadian, however, was not the only language besides his own that the Semitic Babylonian or Assyrian was required to know. Aramaic had become the common language of trade and diplomacy, so that not only was it assumed by the ministers of Hezekiah that an official like the Rab-shakeh or Vizier of Sennacherib could speak it as a matter of course (2 Kings xviii. 26), but even in trading documents we find the Aramaic language and alphabet used side by side with the Assyrian cuneiform. This common use of Aramaic explains how it was that the Jews after the Babylonish captivity gave up their own language in favour not of the Assyro-Babylonian, but of the Aramaic of Northern Syria and Arabia. An educated Assyrian was thus expected to be able to read and write a dead language, Accadian, and to read, write, and speak a foreign living language, Aramaic. In addition to these languages, moreover, he took an interest in others which were spoken by his neighbours around him. The Rab-shakeh of Sennacherib was able to speak Hebrew, and tablets have been discovered giving the Assyrian renderings of lists of words from the barbarous dialects of the Kossśans in the mountains of Elam and of the Semitic nomads on the western side of the Euphrates. All the branches of knowledge known at the time were treated of in Assyrian literature, though naturally history, legend, and poetry occupied a prominent place in it. But even such subjects as the despatches of generals in the field, or the copies of royal correspondence found a place in the public library. The chronology of Assyria, and therewith of the Old Testament also, has been restored by means of the lists of successive 'eponyms' or officers after whom the years were named, while a recent discovery has brought to light a table of Semitic Babylonian kings, arranged in dynasties, which traces them back to B.C. 2330. A flood of light has been poured on Chaldean astronomy and astrology, by the fragments of the original work called 'The Observations of Bel' which was translated into Greek by the Babylonian priest BÍrŰssos. It consisted of seventy-two books, and was compiled for king Sargon of Accad, whose date is assigned by Nabonidos to B.C. 3800. Another work on omens, in 137 books, had been compiled for the same king, and both remained to the last days of the Assyrian Empire the standard treatises on the subjects with which they dealt. To the same period we should probably refer a treatise on agriculture, extracts from which have been preserved in a reading-book in Accadian and Assyrian. Here the songs are quoted with which the Accadian ox-drivers beguiled their labours in the field: 'An heifer am I: to the cow thou art yoked: the plough's handle is strong: lift it up lift it up;' or again: 'The knees are marching, the feet are not resting; with no wealth of thy own grain thou begettest for me.' Some of the most curious specimens of this department of literature are the fables, riddles, and proverbs, which embody the homely wisdom of the unofficial classes.

Part of an Assyrian Cylinder

containing Hezekiah's Name The following is the transcription into the ordinary Assyrian Characters of the last thirteen lines of the photograph on page 104. By way of comparison, a specimen of Babylonian writing is also given here. Specimen of Babylonian Writing from an Inscription of Nebuchadnezzar The following is the transliteration and translation of the transcription on page 105.

Here, for instance, is a riddle propounded to Nergal and the other gods by 'the wise man,' such as Orientals still delight in: 'What is (found) in the house; what is (concealed) in the secret place; what is (fixed) in the foundation of the house; what exists on the floor of the house; what is (perceived) in the lower part (of the house); what goes down by the sides of the house; what in the ditch of the house (makes) broad furrows; what roars like a bull; what brays like an ass; what flutters like a sail; what bleats like a sheep; what barks like a dog; what growls like a bear; what enters into a man; what enters into a woman?' The answer is, of course, the air or wind. Among the most treasured portions of the library of Nineveh was the poetical literature, comprising epics, hymns to the gods, psalms and songs. Fifteen of these songs, we are told, were arranged on the eastern and northern sides of the building, 'on the western side being nine songs to Assur, Bel the voice of the firmament, the Southern Sun,' and another god. The mention of songs to Assur shows that there were some which were of Assyrian origin. The epics, however, all came from Babylonia, and were partly translations from Accadian, partly independent compositions of Semitic Babylonian poets. The names of the reputed authors of many of them have come down to us. Thus the great epic of Gisdhubar was ascribed to Sin-liki-unnini; the legend of EtŠna to Nis-Sin; the fable of the fox to Ru-Merodach the son of Nitakh-Dununa. The epic of Gisdhubar, as has already been stated, contained the account of the Deluge, introduced as an episode into the eleventh book. It consisted in all of twelve books, and was arranged upon an astronomical principle, the subject-matter of each of the books being made to correspond with one of the signs of Zodiac. Thus the fifth book records the death of a monstrous lion at the hands of Gisdhubar, answering to the Zodiacal Leo; in the sixth book the hero is vainly wooed by Istar, the Virgo of the Zodiacal signs; and just as Aquarius is in the eleventh Zodiacal sign, so the history of the Deluge is embodied in the eleventh book. There was a special reason, however, for this arrangement; Gisdhubar himself was a solar hero. He seems originally to have been the fire-stick of the primitive Accadians, and then the god or spirit of the fire it produced, eventually in the Semitic period passing first into a form of the Sun-god, and then into a solar hero. His twelve labours or adventures answer to the twelve months of the year through which the sun moves, like the twelve labours of the Greek HÍraklÍs. The latter, indeed, were simply the twelve labours of Gisdhubar transported to the west. The Greeks received many myths and mythological conceptions from the Phœnicians, along with their early culture, and these myths had themselves been brought by the Phœnicians from their original home in Chaldea. It has long been recognised that HÍraklÍs was the borrowed Phœnician Sun-god; we now know that his primitive prototype had been adopted by the Phœnicians from the Accadians of Babylonia. It is not strange, therefore, that just as in the Greek myth of AphroditÍ and AdŰnis we find the outlines of the old Chaldean story of Istar and Tammuz, so in the legends of HÍraklÍs we find an echo of the legends of Gisdhubar. The lion destroyed by Gisdhubar is the lion of Nemea; the winged bull made by Anu to avenge the slight offered to Istar is the winged bull of Krete; the tyrant Khumbaba, slain by Gisdhubar in 'the land of pine-trees, the seat of the gods, the sanctuary of the spirits' is the tyrant GeryŰn; the gems borne by the trees of the forest beyond 'the gateway of the sun' are the apples of the Hesperides; and the deadly sickness of Gisdhubar himself is but the fever sent by the poisoned tunic of Nessos through the veins of the Greek hero. It is curious thus to trace to their first source the myths which have made so deep an impress on classical art and literature. The indebtedness of European culture to the valley of the Euphrates is becoming more and more apparent every year. It is impossible to determine the age of the great Chaldean epic, but it must have been composed subsequently to the period when, through the precession of the equinoxes, Aries came to be the first sign of the Zodiac instead of Taurus, that is to say, about B.C. 2500. On the other hand, it is difficult to make it later than B.C. 2000, while the whole character and texture of the poem shows that it has been put together from older lays, which have been united into a single whole. The poem deservedly continued to be a favourite among the Babylonians and Assyrians, and more than one edition of it was made for the library of Assur-bani-pal. A translation of all the portions of it that have been discovered will be found in George Smith's 'Chaldean Account of Genesis.' It is difficult for the English reader to appreciate justly the real character of many of these old poems. The tablets on which they are inscribed were broken in pieces when Nineveh was destroyed, and the roof of the library fell in upon them. A text, therefore, has generally to be pieced together from a number of fragments, leaving gaps and lacunś which mar the pleasure of reading it. Then, again, the translator frequently comes across a word or phrase which is new to him, and which he is consequently obliged to leave untranslated or to render purely conjecturally. At times there is a lacuna in the original text itself. When the Assyrian scribe was unable to read the tablet he was copying, either because the characters had been effaced by time or because their Babylonian forms were unknown to him, he wrote the word khibi, 'it is wanting,' and left a blank in his text. It is not wonderful, therefore, that what is really a fine piece of literature reads tamely and poorly in its English dress, more especially when we remember that the decipherer is compelled to translate literally, and cannot have recourse to those idiomatic paraphrases which are permissible when we are dealing with known languages. But it must be confessed that many of the best compositions of Babylonia are spoilt for us by the references to a puerile superstition, and the ever-present dread of witchcraft and magic which they contain. A good example of this curious mixture of exalted thought and debasing superstition is the following hymn to the Sun-god:—

Even the science of the Babylonians and their Assyrian disciples was not free from superstition. Astronomy was mixed with astrology, and their observation of terrestrial phenomena led only to an elaborate system of augury. The false assumption was made that an event was caused by another which had immediately preceded it; and hence it was laid down that whenever two events had been observed to follow one upon the other, the recurrence of the first would cause the other to follow again. The assumption was an illustration of the well-known fallacy: 'Post hoc, ergo propter hoc.' It produced both the pseudo-science of astrology and the pseudo-science of augury. The standard work on astronomy, as has already been noted, was that called 'The Observations of Bel,' compiled originally for the library of Sargon I at Accad. Additions were made to it from time to time, the chief object of the work being to notice the events which happened after each celestial phenomenon. Thus the occurrences which at different periods followed a solar eclipse on a particular day were all duly introduced into the text and piled, as it were, one upon the other. The table of contents prefixed to the work showed that it treated of various matters—eclipses of the sun and moon, the conjunction of the sun and moon, the phases of Venus and Mars, the position of the pole-star, the changes of the weather, the appearance of comets, or, as they are called, 'stars with a tail behind and a corona in front,' and the like. The immense collection of records of eclipses indicates the length of time during which observations of the heavens had been carried on. As it is generally stated whether a solar eclipse had happened 'according to calculation' or 'contrary to calculation,' it is clear that the Babylonians were acquainted at an early date with the periodicity of eclipses of the sun. The beginning of the year was determined by the position of the star Dilgan (α Aurigś) in relation to the new moon at the vernal equinox, and the night was originally divided into three watches. Subsequently the kasbu or 'double hour' was introduced to mark time, twelve kasbu being equivalent to a night and day. Time itself was measured by a clepsydra or water-clock, as well as by a gnomon or dial. The dial set up by Ahaz at Jerusalem (2 Kings xx. 11) was doubtless one of the fruits of his intercourse with the Assyrians. The Zodiacal signs had been marked out and named at that remote period when the sun was still in Taurus at the beginning of spring, and the equator had been divided into sixty degrees. The year was correspondingly divided into twelve months, each of thirty days, intercalary months being counted in by the priests when necessary. The British Museum possesses fragments of a planisphere from Nineveh, representing the sky at the time of the vernal equinox, the constellation of Tammuz or Orion being specially noticeable upon it. Another tablet contains a table of lunar longitudes. With all this attention to astronomical matters it is not surprising that every great city boasted of an observatory, erected on the summit of a lofty tower. Astronomers were appointed by the state to take charge of these observatories, and to send in fortnightly reports to the king. Here are specimens of them, the first of which is dated B.C. 649:—'To the king, my lord, thy servant Istar-iddin-pal, one of the chief astronomers of Arbela. May there be peace to the king, my lord, may Nebo, Merodach, and Istar of Arbela, be favourable to the king, my lord. On the twenty-ninth day we kept a watch. The observatory was covered with cloud: the moon we did not see. (Dated) the month Sebat, the first day, the eponymy of Bel-kharran-Sadua.' 'To the king, my lord, thy servant Abil-Istar. May there be peace to the king, my lord. May Nebo and Merodach be propitious to the king, my lord. May the great gods grant unto the king, my lord, long days, soundness of body, and joy of heart. On the twenty-seventh day (of the month) the moon disappeared. On the twenty-eighth, twenty-ninth, and thirtieth days, we kept a watch for the eclipse of the sun. But the sun did not pass into eclipse. On the first day the moon was seen during the day. During the month Tammuz (June) it was above the planet Mercury, as I have already reported to the king. During the period when the moon is called Anu (i.e., from the first to the fifth days of the lunar month), it was seen declining in the orbit of Arcturus. Owing to the rain the horn was not visible. Such is my report. During the period when the moon was Anu, I sent to the king, my lord, the following account of its conjunction:—It was stationary and visible below the star of the chariot. During the period when the moon is called Bel (i.e., from the tenth to the fifteenth day), it became full; to the star of the chariot it approached. Its conjunction (with the star) was prevented; but its conjunction with Mercury, during the period when it was Anu, of which I have already sent a report to the king, my lord, was not prevented. May the king, my lord, have peace!' Astronomical observations imply a knowledge of mathematics, and in this the Babylonians and Assyrians seem to have excelled. Tables of squares and cubes have been found at Senkereh, the ancient Larsa, and a series of geometrical figures used for augural purposes presupposes a sort of Babylonian Euclid. The mathematical unit was 60, which was understood as a multiple when high numbers had to be expressed, IV, for example, standing for (4 ◊ 60 =) 240. Similarly, 60 was the unwritten denominator of fractional numbers. The plan of an estate outside the gate of Zamama at Babylon, and belonging to the time of Nebuchadnezzar, has been discovered, while the famous Hanging Gardens of that city were watered by means of a screw. Medicine also was in a more advanced state than might have been expected. Fragments of an old work on medicine have been found, which show that all known diseases had been classified, and their symptoms described, the medical mixtures considered appropriate to each being compounded and prescribed quite in modern fashion. Here is one of them: 'For a diseased gall-bladder, which devours the top of a man's heart like a ring(?) ... within the sick (part), we prepare cypress-extract, goats' milk, palm-wine, barley, the flesh of an ox and bear, and the wine of the cellarer, in order that the sick man may live. Half an ephah of clear honey, half an ephah of cypress-extract, half an ephah of gamgam herbs, half an ephah of linseed, half an ephah of ..., half an ephah of imdi herbs, half an ephah of the seed of tarrati, half an ephah of calves' milk, half an ephah of senu wood, half an ephah of tik powder, half an ephah of the ... of the river-god, half an ephah of usu wood, half an ephah of mountain medicine, half an ephah of the flesh(?) of a dove, half an ephah of the seed of the ..., half an ephah of the corn of the field, ten measures of the juice of a cut herb, ten measures of the tooth of the sea (sea-weed), one ephah of putrid flesh(?), one ephah of dates, one ephah of palm-wine and insik, and .* one ephah of the flesh(?) of the entrails; slice and cut up; or mix as a mixture, after first stirring it with a reed. On the fourth day observe (the sick man's) countenance. If it shows a white appearance his heart is cured; if it shows a dark appearance his heart is still devoured by the fire; if it shows a yellow appearance during the day, the patient's recovery is assured; if it shows a black appearance he will grow worse and will not live. For the swelling(?), slice (the flesh of) a cow which has entered the stall and has been slaughtered during the day. Seethe it in water and calves' milk. Drink the result in palm-wine. Drink it during the day.' Generally, however, the prescriptions are not so elaborate as this. They are more usually of this nature: 'For low spirits, slice the root of the destiny tree, the root of the susum tree, two or three other vegetable compounds, and the tongue of a dog. Drink the mixture either in water or in palm-wine.' Even medical science, however, was invaded by superstition. In place of trying the doctor's prescription, a patient often had the choice allowed him of having recourse to charms and exorcisms. Thus the medical work itself permits him to 'place an incantation on the big toe of the left foot and cause it to remain' there, the incantation being as follows: 'O wind, my mother, wind, wind, the handmaid of the gods art thou; O wind among the storm-birds; yea, the water dost thou make stream down, and with the gods thy brothers liftest up the glory of thy wisdom.' At other times a witch or sorceress was called in, and told to 'bind a cord twice seven times, binding it on the sick man's neck and on his feet like fetters, and while he lies in his bed to pour pure water over him.' Instead of the knotted cord verses from a sacred book might be employed, just as phylacteries were, and still are, among the Jews. Thus we read: 'In the night-time let a verse from a good tablet be placed on the head of the sick man in bed.' The word translated 'verse' is masal, the Hebrew m‚sh‚l, which literally signifies a 'proverb' or 'parable.' It is curious to find the witch by the side of the wizard in Babylonia. 'The wise woman,' however, was held in great repute there, and just as the witches of Europe were supposed to fly through the air on a broomstick so it was believed that the witches of Babylonia could perform the same feat with the help of a wooden staff.

|

|

|

|

|

6) D.P. stands for 'Determinative Prefix.' There are thirty determinatives in Assyrian.

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD