By-Paths of Bible Knowledge

Book # 7 - Assyria - Its Princes, Priests, and People

By A. H. Sayce M.A.

Chapter 2

Assyrian HistoryAssyrian history, as we have seen, begins with the patesis or viceroys of the city of Assur. We know little about them except their names; contemporaneous annals do not commence until Assyria has ceased to be the dependency of a foreign power, and has become an independent kingdom. It was in the 17th or 16th century before the Christian era that Bel-kapkapi first gave himself the title of king. For two or three centuries afterwards our chief information about the monarchy he founded is derived from the relations, sometimes hostile and sometimes peaceable, which his successors had with Babylonia. One of them, however, Rimmon-nirari I by name (about B.C. 1320), has left us an inscription in which he recounts the wars he waged against the Babylonians, the Kurds, the Aramæans, and the Shuites, nomad tribes who extended along the western bank of the Euphrates. It was his son, Shalmaneser I, to whom the foundation of Calah is ascribed. For six generations his descendants followed one another on the throne; then came Tiglath-Pileser I, who may be regarded as the founder of the first Assyrian Empire. He carried his arms as far as Cilicia and Malatiyeh on the west, and the wild tribes of Kurdistan on the east; he overthrew the Moschi or Meshech, defeated the Hittites and their Colchian allies, and erected a memorial of his conquests at the sources of the Tigris. The Hittite city of Pethor, at the junction of the Euphrates and Sajur, was garrisoned with Assyrian soldiers, and at Arvad the Assyrian monarch symbolised his subjection of the Mediterranean by embarking in a ship and killing a dolphin in the sea. In Nineveh he established a botanical garden, which he filled with the strange trees he had brought back with him from his campaigns. In B.C. 1130 he marched into Babylonia, and, after a momentary repulse at the hands of the Babylonian king, defeated his antagonists on the banks of the Lower Zab. Babylonia was ravaged, and Babylon itself was captured. With the death of Tiglath-Pileser I, Assyrian history becomes for awhile obscure. The sceptre fell into feeble hands, and the distant conquests of the empire were lost. It was during this period of abeyance that the kingdom of David and Solomon arose in the west. The Assyrian power did not revive until the reign of Assur-dân II, whose son, Rimmon-nirari II (B.C. 911-889), and great-grandson, Assur-natsir-pal ( B.C. 883-858), led their desolating armies through Western Asia, and made the name of Assyria once more terrible to the nations around them. Assur-natsir-pal was at once one of the most ferocious and most energetic of the Assyrian kings. His track was marked by impalements, by pyramids of human heads, and by other barbarities too horrible to be described. But his campaigns reached further than those of Tiglath-Pileser had done. Armenia, Mesopotamia, and Kurdistan, were overrun again and again; the Babylonians were forced to sue for peace; Sangara, the Hittite king of Carchemish, paid tribute, and the rich cities of Phœnicia poured their offerings into the treasury of Nineveh. The armies of Assyria penetrated even to Nizir, where the ark of the Chaldæan Noah was believed to have rested on the peak of Rowandiz. In Assyria itself the cities were embellished with the spoils of foreign conquest; splendid palaces were erected, and Calah, which had fallen into decay, was restored. A library was erected there, and it became the favourite residence of Assur-natsir-pal. He was succeeded by his son Shalmaneser II, so named, perhaps, after the original founder of Calah. Shalmaneser's military successes exceeded even those of his father, and his long reign of thirty-five years marks the climax of the first Assyrian Empire. His annals are chiefly to be found engraved on three monuments now in the British Museum. One of these is a monolith from Kurkh, a place about twenty miles from Diarbekr. The full-length figure of Shalmaneser is sculptured upon it, and the surface of the stone is covered with the inscription. Another monument is a small 'obelisk' of polished black stone, the upper part of which is shaped like three ascending steps. Inscriptions run round its four sides, as well as small bas-reliefs representing the tribute offered to 'the great king' by foreign states. Among the tribute-bearers are the Israelitish subjects of 'Jehu, son of Omri.' The third monument is one which was discovered in 1878 at Balawât, about nine miles from Nimrûd or Calah. It consists of the bronze framework of two colossal doors, of rectangular shape, twenty-two feet high and twenty-six feet broad. The doors opened into a temple, and were made of wood, to which the bronze was fastened by means of nails. The bronze was cut into bands, which ran in a horizontal direction across the doors, and were each divided into two lines of embossed reliefs. These reliefs were hammered out, and not cast, and the rudeness of their execution proves that they were the work of native artists, and not of the Phœnician settlers in Nineveh, of whose skill in such work we have several specimens. Short texts are added to explain the reliefs, so that the various campaigns and cities represented in them can all be identified. Among the cities is the Hittite capital Carchemish, and the warriors of Armenia are depicted in a costume strikingly similar to that of the ancient Greeks. Shalmaneser's first campaign was against the restless tribes of Kurdistan. He then turned northward, and fell upon the Armenian king of Van and the Mannâ or Minni (see Jer. li. 27), who inhabited the country between the mountains of Kotûr and Lake Urumiyeh. The Hittites of Carchemish, with their allies from Cilicia and other neighbouring districts, were next compelled to sue for peace, and the acquisition of Pethor, which had been lost after Tiglath-Pileser's death, again gave the Assyrians the command of the ford over the Euphrates. The result of this was, that in B.C. 854 Shalmaneser came into conflict with the kingdom of Hamath. The common danger had roused Hadadezer of Damascus, called Benhaded II in the Bible, to make common cause with Hamath, and a confederacy was formed to resist the Assyrian advance. Among the confederates 'Ahab of Israel' is mentioned as furnishing the allies with 2,000 chariots and 10,000 infantry. But the confederacy was shattered at Karkar or Aroer, although Shalmaneser had himself suffered too severely to be able to follow up his victory. For a time, therefore, Syria remained unmolested, and the Assyrian king turned his attention to Babylonia, which he reduced to a state of vassalage, under the pretext of assisting the Babylonian sovereign against his rebel brother. Twelve years, however, after the battle of Karkar, Shalmaneser was once more in the west. Hadadezer had been succeeded by Hazael on the throne of Damascus, and it was against him that the full flood of Assyrian power was turned. For some time he managed to stem it, but in B.C. 841 he suffered a crushing defeat on the heights of Shenir (see Deut. iii. 9), and his camp, along with 1,121 chariots and 470 carriages, fell into the hands of the Assyrians, who proceeded to besiege him in his capital, Damascus. The siege, however, was soon raised, and Shalmaneser contented himself with ravaging the Hauran and marching to Beyrout, where his image was carved on the rocky promontory of Baal-rosh, at the mouth of the Nahr el-Kelb. It was while he was in this neighbourhood that the ambassadors of Jehu arrived with offers of tribute and submission. The tribute, we are told, consisted of 'silver, gold, a golden bowl, vessels of gold, goblets of gold, pitchers of gold, a sceptre for the king's hand and spear-handles,' and Jehu is erroneously entitled 'the son of Omri.' After the defeat of Hazael Shalmaneser's expeditions were only to distant regions like Phœnicia, Kappadokia, and Armenia, for the sake of exacting tribute. No further attempt was made at permanent conquest, and after B.C. 834 the old king ceased to lead his armies in person, the tartan or commander-in-chief taking his place. Not long afterwards a revolt broke out headed by his eldest son, who seems to have thought that he would have little difficulty in wresting the sceptre from the hands of the enfeebled king. Twenty-seven cities, including Nineveh and Assur, joined the revolt, which was, however, finally put down by the energy and military capacity of Shalmaneser's second son Samas-Rimmon, who succeeded him soon afterwards (B.C. 823-810). On his death he was followed by his son Rimmon-nirari III (810-781), who compelled Mariha of Damascus to pay him tribute, as well as the Phœnicians, Israelites, Edomites, and Philistines. But the vigour of the dynasty was beginning to fail. A few short reigns followed that of Rimmon-nirari, during which the first Assyrian Empire melted away. A formidable power arose in Armenia, the Assyrian armies were driven to the frontiers of their own country, and disaffection began to prevail in Assyria itself. At length, on the 15th of June, B.C. 763, an eclipse of the sun took place, and the city of Assur rose in revolt. The revolt lasted three years, and before it could be crushed the outlying provinces were lost. When Assur-nirari, the last of his line, ascended the throne in B.C. 753, the empire was already gone, and the Assyrian cities themselves were surging with discontent. Ten years later the final blow was struck; the army declared itself against their monarch, and he and his dynasty fell together. On the 30th of Iyyar of the year B.C. 745, a military adventurer, Pul, seized the vacant crown, and assumed the venerable name of Tiglath-Pileser. If we may believe Greek tradition, Tiglath-Pileser II began life as a gardener. Whatever might have been his origin, however, he proved to be a capable ruler, a good general, and a far-sighted administrator. He was the founder of the second Assyrian Empire, which differed essentially from the first. The first empire was at best a loosely-connected military organization; campaigns were made into distant countries for the sake of plunder and tribute, but little effort was made to retain the districts that had been conquered. Almost as soon as the Assyrian armies were out of sight, the conquered nations shook off the Assyrian yoke, and it was only in regions bordering on Assyria that garrisons were left by the Assyrian king. And whenever the Assyrian throne was occupied by a weak or unwarlike prince, even these were soon destroyed or forced to retreat homewards. Tiglath-Pileser II, however, consolidated and organised the conquests he made; turbulent populations were deported from their old homes, and the empire was divided into satrapies or provinces, each of which paid a fixed annual tribute to the imperial exchequer. For the first time in history the principle of centralisation was carried out on a large scale, and a bureaucracy began to take the place of the old feudal nobility of Assyria. But the second Assyrian Empire was not only an organised and bureaucratic one, it was also commercial. In carrying out his schemes of conquest Tiglath-Pileser II was influenced by considerations of trade. His chief object was to divert the commerce of Western Asia into Assyrian hands. For this purpose every effort was made to unite Babylonia with Assyria, to overthrow the Hittites of Carchemish, who held the trade of Asia Minor, as well as the high road to the west, and to render Syria and the Phœnician cities tributary. The policy inaugurated by Tiglath-Pileser was successfully followed up by his successors. Babylonia was the first to feel the results of the change of dynasty at Nineveh. The northern part of it was annexed to Assyria, and secured by a chain of fortresses. Tiglath-Pileser now attacked the Kurdish tribes, who were constantly harassing the eastern frontier of the kingdom, and chastised them severely, the Assyrian army forcing its way through the fastnesses of the Kurdish mountains into the very heart of Media. But Ararat, or Armenia, was still a dangerous neighbour, and accordingly Tiglath-Pileser's next campaign was against a confederacy of the nations of the north headed by Sarduris of Van. The confederacy was utterly defeated in Kommagênê, 72,950 prisoners falling into the hands of the Assyrians, and the way was opened into Syria. In B.C. 742 the siege of Arpad (now Tel Erfâd) began, and lasted two years. Its fall brought with it the submission of Northern Syria, and it was next the turn of Hamath to be attacked. Hamath was in alliance with Uzziah of Judah, and its king Eniel may have been of Jewish extraction. But the alliance availed nothing. Hamath was taken by storm, part of its population transported to Armenia, and their places taken by colonists from distant provinces of the empire, while nineteen of the districts belonging to it were annexed to Assyria. The kings of Syria now flocked to render homage and offer tribute to the Assyrian conqueror. Among them we read the names of Menahem of Samaria, Rezon of Syria, Hiram of Tyre, and Pisiris of Carchemish. This was the occasion when, as we learn from 2 Kings xv. 19, Menahem gave a thousand talents of silver to the Assyrian king Pul, the name under which Tiglath-Pileser continued to be known in Babylonia, and, as the Old Testament informs us, in Palestine also. Three years later Ararat was again invaded. Van, the capital, was blockaded, and though it successfully resisted the Assyrians, the country was devastated far and near for a space of 450 miles. It was long before the Armenians recovered from the blow, and for the next century they ceased to be formidable to Assyria. Tiglath-Pileser's northern frontier was now secure, and he therefore gladly seized the opportunity of interfering in the affairs of the west which was offered him by Ahaz, the Jewish king. Ahaz, whom the Assyrian inscriptions call Jehoahaz, had been hard pressed by Rezon of Damascus and Pekah of Israel, who had combined to overthrow the Davidic dynasty and place a vassal prince, 'the son of Tabeal,' on the throne of Jerusalem. Ahaz in his extremity called in the aid of Tiglath-Pileser, offering him a heavy bribe and acknowledging his supremacy. Tiglath-Pileser accordingly marched into Syria; Rezon was utterly defeated in battle and then besieged in Damascus, to which he had escaped. Damascus was closely invested; the trees in its neighbourhood were cut down; the districts dependent on it were ravaged, and forces were despatched to punish the Israelites, Ammonites, Moabites, and Philistines, who had been the allies of Rezon, Gilead and Abel-beth-maachah being burnt, and the tribes beyond the Jordan carried into captivity. The Philistine cities were compelled to open their gates; the king of Ashkelon committed suicide in order not to fall into the hands of the enemy, and Khanun of Gaza fled to Egypt. At last in B.C. 732, after a siege of two years, Damascus was forced by famine to surrender. Rezon was slain, Damascus given over to plunder and ruin, and its inhabitants transported to Kir. Syria became an Assyrian province, and all its princes were summoned to do homage to the conqueror, while Tyre was fined 150 talents of gold, or about £400,000. Among the princes who attended the levée or 'durbar' was Ahaz, and it was while he was attending it that he saw the altar of which he sent a pattern to Urijah the priest (2 Kings xvi. 10). All that now remained for Tiglath-Pileser to do was to reduce Babylonia as he had reduced Syria. In B.C. 731, accordingly, he marched again into Chaldæa. Ukin-ziru, the Babylonian king, was slain, Babylon and other great cities were taken, and in B.C. 729, under his original name of Pul, Tiglath-Pileser assumed the title of 'king of Sumer (Shinar) and Accad.' He lived only two years after this, and died in B.C. 727, when the crown was seized by Elulæos of Tinu, who took the name of Shalmaneser IV. Shalmaneser's short reign was signalised by an unsuccessful attempt to capture Tyre, and by the beginning of a war against the kingdom of Israel. But the siege of Samaria was hardly commenced when Shalmaneser died, or was murdered, in B.C. 722, and was succeeded by another usurper who assumed the name of Sargon, one of the most famous of the early Babylonian kings. Sargon in his inscriptions claims royal descent, but the claim was probably without foundation. He proved to be an able general, though his inscriptions show that he continued to the last to be a rough but energetic soldier who had perhaps risen from the ranks. Two years after his accession (B.C. 720) Samaria was taken and placed under an Assyrian governor, 27,280 of its leading inhabitants being carried captive to Gozan and Media. But Sargon soon found that the task of cementing and completing the empire founded by Tiglath-Pileser was by no means an easy one. Babylonia had broken away from Assyria on the news of Shalmaneser's death, and had submitted itself to Merodach-Baladan the hereditary chieftain of Beth-Yagina in the marshes on the coast of the Persian Gulf. The southern portion of Sargon's dominions was threatened by the ancient and powerful kingdom of Elam; the Kurdish tribes on the east renewed their depredations; while the Hittite kingdom of Carchemish still remained unsubdued, and the Syrian conquests could with difficulty be retained. In fact, a new enemy appeared in this part of the empire in the shape of Egypt. Sargon's first act, therefore, was to drive the Elamites back to their own country with considerable loss. He was then recalled to the west by the revolt of Hamath, where Yahu-bihdi, or Ilu-bihdi, whose name perhaps indicates his Jewish parentage, had proclaimed himself king, and persuaded Arpad, Damascus, Samaria, and other cities to follow his standard. But the revolt was of short duration. Hamath was burnt, 4,300 Assyrians being sent to occupy its ruins, and Yahu-bihdi was flayed alive. Sargon next marched along the sea-coast to the cities of the Philistines. There the Egyptian army was routed at Raphia, and its ally, Khanun of Gaza, taken captive. In B.C. 717 all was ready for dealing the final blow at the Hittite power in Northern Syria. The rich trading city of Carchemish was stormed, its last king, Pisiris, fell into the hands of the Assyrians, and his Moschian allies were forced to retreat to the north. The plunder of Carchemish brought eleven talents and thirty manehs of gold and 2,100 talents of silver into the treasury of Calah. It was henceforth placed under an Assyrian satrap, who thus held in his hands the key of the high road and the caravan trade between Eastern and Western Asia. But Sargon was not allowed to retain possession of Carchemish without a struggle. Its Hittite inhabitants found avengers in the allied populations of the north, in Meshech and Tubal, in Ararat and Minni. The struggle lasted for six years, but in the end Sargon prevailed. Van submitted, its king Ursa, the leader of the coalition against Assyria, committed suicide, Cilicia and the Tibareni or Tubal were placed under an Assyrian governor, and the city of Malatiyeh was razed to the ground. In B.C. 711, Sargon was at length free to turn his attention to the west. Here affairs wore a threatening aspect. Merodach-Baladan, foreseeing that his own turn would come as soon as Sargon had firmly established his power in Northern Syria, had despatched ambassadors to the Mediterranean states, urging them to combine with him against the common foe. We read in the Bible of the arrival of the Babylonian embassy in Jerusalem, and of the rebuke received by Hezekiah for his vainglory in displaying to the strangers the resources of his kingdom. In spite of Isaiah's warning, Hezekiah listened to the persuasions of the Babylonian envoys, and encouraged by the promise of Egyptian support along with Phœnicia, Moab, Edom, and the Philistines, determined to defy the Assyrian king. But before the confederates were ready to act in concert Sargon descended upon Palestine. Phœnicia and Judah were overrun, Jerusalem was captured, and Ashdod burnt, while the Egyptians made no attempt to help their friends. This siege of Ashdod is the only occasion on which the name of Sargon occurs in the Bible (Isaiah xx. 1). As soon as all source of danger was removed in the west Sargon hurled his forces against Babylonia. Merodach-Baladan had made every preparation to meet the coming attack, and the Elamite king had engaged to help him. But the Elamites were again compelled to fly before the warriors of Assyria, and Sargon entered Babylon in triumph (B.C. 710). The following year he pursued Merodach-Baladan to his ancestral stronghold in the marshes; Beth-Yagina was taken by storm, and its unfortunate defenders were sent in chains to Nineveh. Sargon was now at the height of his power. His empire was a compact and consolidated whole, reaching from the Mediterranean on the west to the mountains of Elam on the east, and his solemn coronation at Babylon gave a title to his claim to be the legitimate successor of the ancient Sargon of Accad. The old kingdoms of Elam and Egypt alone remained to threaten the newly-founded empire, which received the voluntary homage of the smaller states that lay immediately beyond it. Thus the sacred island of Dilvun in the Persian Gulf submitted itself to the terrible conqueror, and the Phœnicians of Kition or Chittim in Cyprus erected a monumental record of his supremacy. Sargon's end was consonant with his whole career. He was murdered by his soldiers in his new city of Dur-Sargon or Khorsabad, on the 12th of Ab or July, B.C. 705, and was succeeded by his son Sennacherib. If we may judge from Sennacherib's name, which means 'the Moon-god has increased the brothers,' he would not have been Sargon's eldest son. In any case he had been brought up in the purple, and displayed none of the rugged virtues of his father. He was weak, boastful, and cruel, and preserved his empire only by the help of the veterans and generals whom Sargon had trained. Merodach-Baladan had escaped from captivity, and two years after the death of Sargon had once more possessed himself of Babylon. But a battle at Kis drove him from the country nine months subsequently, and Sennacherib was able to turn his attention to affairs in the west. In B.C. 701, he marched into Phœnicia and Palestine, where Hezekiah of Judah and some of the neighbouring kings had refused their tribute. Tirhakah, the Ethiopian king of Egypt, had promised support to the rebellious states, and Padi, the king of Ekron, who remained faithful to the Assyrians, was carried in chains to Jerusalem. The Assyrian army fell first upon Phœnicia. Great and Little Sidon, Sarepta, Acre, and other towns, surrendered, Elulæos, the Sidonian monarch, fled to Cyprus, and the kings of Arvad and Gebal offered homage. Metinti of Ashdod, Pedael of Ammon, Chemosh-nadab of Moab, and Melech-ram of Edom, also submitted. Then, says Sennacherib: 'Zedekiah, king of Ashkelon, who had not submitted to my yoke, himself, the gods of the house of his fathers, his wife, his sons, his daughters, and his brothers, the seed of the house of his fathers, I removed, and I sent him to Syria. I set over the men of Ashkelon Sarludari, the son of Rukipti, their former king, and I imposed upon him the payment of tribute, and the homage due to my majesty, and he became a vassal. In the course of my campaign I approached and captured Beth-Dagon, Joppa, Bene-berak, and Azur, the cities of Zedekiah, which did not submit at once to my yoke, and I carried away their spoil. The priests, the chief men, and the common people of Ekron who had thrown into chains their king Padi because he was faithful to his oaths to Assyria, and had given him up to Hezekiah, the Jew, who imprisoned him like an enemy in a dark dungeon, feared in their hearts. The king of Egypt, the bowmen, the chariots, and the horses of the king of Ethiopia, had gathered together innumerable forces, and gone to their assistance. In sight of the town of Eltekeh was their order of battle drawn up; they called their troops (to the battle). Trusting in Assur, my lord, I fought with them and overthrew them. My hands took the captains of the chariots, and the sons of the king of Egypt, as well as the captains of the chariots of the king of Ethiopia, alive in the midst of the battle. I approached and captured the towns of Eltekeh and Timnath, and I carried away their spoil. I marched against the city of Ekron, and put to death the priests and the chief men who had committed the sin (of rebellion), and I hung up their bodies on stakes all round the city. The citizens who had done wrong and wickedness I counted as a spoil; as for the rest of them who had done no sin or crime, in whom no fault was found, I proclaimed a free pardon. I had Padi, their king, brought out from the midst of Jerusalem, and I seated him on the throne of royalty over them, and I laid upon him the tribute due to my majesty. But as for Hezekiah of Judah, who had not submitted to my yoke, forty-six of his strong cities, together with innumerable fortresses and small towns which depended on them, by overthrowing the walls and open attack, by battle engines and battering-rams, I besieged, I captured, I brought out from the midst of them and counted as a spoil 200,150 persons, great and small, male and female, horses, mules, asses, camels, oxen and sheep without number. Hezekiah himself I shut up like a bird in a cage in Jerusalem, his royal city. I built a line of forts against him, and I kept back his heel from going forth out of the great gate of his city. I cut off his cities that I had spoiled from the midst of his land, and gave them to Metinti, king of Ashdod, Padi, king of Ekron, and Zil-baal, king of Gaza, and I made his country small. In addition to their former tribute and yearly gifts, I added other tribute, and the homage due to my majesty, and I laid it upon them. The fear of the greatness of my majesty overwhelmed him, even Hezekiah, and he sent after me to Nineveh, my royal city, by way of gift and tribute, the Arabs and his body-guard whom he had brought for the defence of Jerusalem, his royal city, and had furnished with pay, along with thirty talents of gold, 800 talents of pure silver, carbuncles and other precious stones, a couch of ivory, thrones of ivory, an elephant's hide, an elephant's tusk, rare woods of various names, a vast treasure, as well as the eunuchs of his palace, dancing-men and dancing-women; and he sent his ambassador to offer homage.' In this account of his campaign Sennacherib discreetly says nothing about the disaster which befell his army in front of Jerusalem, and which obliged him to return ignominiously to Assyria without attempting to capture Jerusalem, and to deal with Hezekiah as it was his custom to deal with other rebellious kings. The tribute offered by Hezekiah at Lachish, when he vainly tried to buy off the threatened Assyrian attack, is represented as having been the final result of a successful campaign. There is, however, no exaggeration in the amount of silver Sennacherib claims to have received, since 800 talents of silver are equivalent to the 500 talents stated by the Bible to have been given, when reckoned according to the standard of value in use at the time in Nineveh. Sennacherib never recovered from the blow he had suffered in Judah. He made no more expeditions against Palestine, and during the rest of his reign Judah remained unmolested. Babylonia, moreover, gave him constant trouble. In the year after his campaign in the west (B.C. 700) a Chaldean, named Nergal-yusezib, stirred up a revolt which Sennacherib had some difficulty in suppressing. Two years later he appointed his eldest son, Assur-nadin-sumi, viceroy of Babylon. In B.C. 694, he determined to attack the followers of Merodach-Baladan in their last retreat at the mouth of the Eulæus, where land had been given to them by the Elamite king after their expulsion from Babylonia. Ships were built and manned by Phœnicians in the Persian Gulf, by means of which the settlements of the Chaldean refugees were burnt and destroyed. Meanwhile, however, Babylonia itself was invaded by the Elamites; the Assyrian viceroy was carried into captivity, and Nergal-yusezib placed on the throne of the country. He defeated the Assyrian forces in a battle near Nipur, but died soon afterwards, and was followed by Musezib-Merodach, who like his predecessor is called Suzub in Sennacherib's inscriptions. He defied the Assyrian power for nearly four years. But in B.C. 690 the combined Babylonian and Elamite army was overthrown in the decisive battle of Khalule, and before another year was past Sennacherib had captured Babylon, and given it up to fire and sword. Its inhabitants were sold into slavery, and the waters of the Araxes canal allowed to flow over its ruins. Sennacherib now assumed the title of king of Babylonia, but with the exception of a campaign into the Cilician mountains he seems to have undertaken no more military expeditions. The latter years of his life were passed in constructing canals and aqueducts, in embanking the Tigris, and in rebuilding the palace of Nineveh on a new and sumptuous scale. On the 20th of Tebet, or December, B.C. 681, he was murdered by his two elder sons, Adrammelech and Nergal-sharezer, who were jealous of the favour shown to their younger brother, Esar-haddon. Esar-haddon was at the time conducting a campaign against Erimenas, king of Armenia, to whom his insurgent brothers naturally fled. Between seven and eight weeks after the murder of the old king, a battle was fought near Malatiyeh, in Kappadokia, between the veterans of Esar-haddon and the forces under his brothers and Erimenas, which ended in the complete defeat of the latter. Esar-haddon was proclaimed king, and the event proved that a wiser choice could not have been made. His military genius was of the first order, but it was equalled by his political tact. He was the only king of Assyria who endeavoured to conciliate the nations he had conquered. Under him the fabric of the Second Empire was completed by the conquest of Egypt. In the first year of his reign he rebuilt Babylon, giving it back its captured deities, its plunder, and its people. Henceforth Babylon became the second capital of the empire, the court residing alternately there and at Nineveh. It was while Esar-haddon was holding his winter court at Babylon that Manasseh, of Judah, was brought to him as prisoner.1 The trade of Phœnicia was diverted into Assyrian hands by the destruction of Sidon. The caravan-road from east to west was at the same time rendered secure by an expedition into the heart of Northern Arabia. Here Esar-haddon penetrated as far as the lands of Huz and Buz, 280 miles of the march being through a waterless desert. The feat has never been excelled, and the terror it inspired among the Bedouin tribes was not forgotten for many years. The northern frontiers of the kingdom were also made safe by the defeat of Teispes, the Kimmerian, who was driven westward with his hordes into Asia Minor. In the east the Assyrian monarch was bold enough to occupy and work the copper-mines on the distant borders of Media, the very name of which had scarcely been heard of before. Westward, the kings of Cyprus paid homage to the great conqueror, and among the princes who sent materials for his palace at Nineveh were Cyprian rulers with Greek names. But the principal achievement of Esar-haddon's reign was his conquest of the ancient monarchy of Egypt. In B.C. 675 the Assyrian army started for the banks of the Nile. Four years later Memphis was taken on the 22nd of Tammuz, or June, and Tirhakah, the Egyptian king, compelled to fly first to Thebes, and then into Ethiopia. Egypt was divided into twenty satrapies, governed partly by Assyrians, partly by native princes, whose conduct was watched by Assyrian garrisons. On his return to Assyria Esar-haddon associated Assur-bani-pal, the eldest of his four sons, in the government on the 12th of Iyyar, or April, B.C. 669, and died two years afterwards (on the 12th of Marchesvan, or October), when again on his way to Egypt. Assur-bani-pal, the Sardanapalos of the Greeks, succeeded to the empire, his brother, Samas-sum-yukin, being entrusted with the government of Babylonia. Assur-bani-pal is probably the 'great and noble' Asnapper of Ezra iv. 10. He was luxurious, ambitious, and cruel, but a munificent patron of literature. The libraries of Babylonia were ransacked for ancient texts, and scribes were kept busily employed at Nineveh in inscribing new editions of older works. But unlike his fathers, Assur-bani-pal refused to face the hardships of a campaign. His armies were led by generals, who were required to send despatches from time to time to the king. It was evident that a purely military empire, like that of Assyria, could not last long, when its ruler had himself ceased to take an active part in military affairs. At first the veterans of his father preserved and even extended the empire of Assur-bani-pal; but before his death it was shattered irretrievably. It is characteristic of Assur-bani-pal that his lion-hunts were mere battues, in which tame animals were released from cages and lashed to make them run; in curious contrast to the lion-hunts in the open field in which his warlike predecessors had delighted.

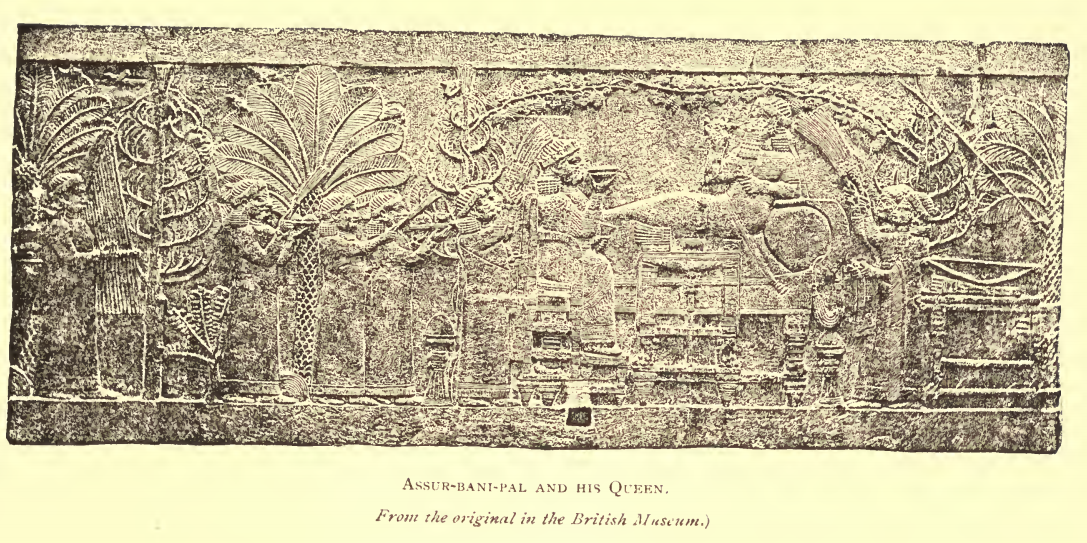

Assur-bani-pal and his Queen His first occupation was to crush a revolt in Egypt. Tirhakah was once more driven out of the country, and Thebes, called Ni in the Assyrian texts, and No-Amon, or 'No of the god Amun' in Scripture, was plundered and destroyed. Its temples were hewed in pieces, and two of its obelisks, weighing 70 tons in all, were carried as trophies to Nineveh. It is to this destruction of the old capital of the Pharaohs that Nahum refers in his prophecy (iii. 8). Meanwhile Tyre had been besieged and forced to surrender, and Cilicia had paid homage to the Assyrian king. Gog, or Gyges, of Lydia, too, voluntarily sent him tribute, including two Kimmerian chieftains whom the Lydian sovereign had captured in battle. When the Lydian ambassadors arrived in Nineveh they found no one who could understand their language; in fact, the very name of Lydia had been unknown to the Assyrians before. The Assyrian Empire had now reached its widest limits. Elam had fallen after a long and arduous struggle. Shushan, its capital, was razed to the ground, and the three last Elamite kings were bound to the yoke of Assur-bani-pal's chariot, and made to drag their conqueror through the streets of Nineveh. The Kedarites and other nomad tribes of Northern Arabia were also chastised, the land of the Minni was overrun, and the Armenians of Van begged for an alliance with the Assyrian king. But while at the very height of his prosperity, the empire was fast slipping away from under Assur-bani-pal's feet. In B.C. 652 a rebellion broke out headed by his brother, the Babylonian viceroy, which shook it to the foundations. Babylonia, Egypt, Palestine, and Arabia made common cause against the oppressor. Lydia sent Karian and Ionic mercenaries to Psammetikhos of Sais, with whose help he succeeded in overthrowing his brother satraps, and in delivering Egypt from the Assyrian yoke. The revolt in Babylonia took long to quell, and for a time the safety of Assur-bani-pal himself was imperilled. At last in 647 Babylon and Cuthah were reduced by famine, and Samas-sum-yukin burnt himself to death in his palace. Fire and sword were carried through Elam, and the last of its monarchs became an outlawed fugitive. When Assyria finally emerged from the deadly struggle, Egypt was lost to it for ever, and Babylonia was but half subdued. The latter province was placed under the government of Kandalanu, who ruled over it for twenty-two years, more like an independent sovereign than a viceroy. His successor, Nabopolassar, the father of Nebuchadnezzar, threw off all semblance of submission to Nineveh, and prepared the way for the empire of his son. But meanwhile the once proud kingdom of Assyria had been contending for bare existence. Assur-bani-pal's son, Assur-etil-ilani, rebuilt with diminished splendour the palace of Calah, which seems to have been burnt by some victorious enemy; and when the last Assyrian king, Esar-haddon II, called Sarakos by the Greeks, mounted the throne, he found himself surrounded on all sides by threatening foes. Kaztarit or Kyaxares, Mamitarsu the Median, the Kimmerians, the Minni, and the people of Sepharad leagued themselves together against the devoted city of Nineveh. The frontier towns fell first, and though Esar-haddon in his despair proclaimed public fasts and prayers to the gods, nothing could ward off the doom pronounced by God's prophets against Nineveh so long before. Nineveh was besieged, captured, and utterly destroyed; and the second Assyrian Empire perished more hopelessly and completely than the first. All that survived was the old capital of the country, Assur, whose former inhabitants were allowed to return to it by Cyrus at the time when the Jewish exiles also were released from their captivity in Babylon.2

|

|

|

|

|

1) 2 Chr. xxxiii. 11. 2) The following are the significations of the different Assyrian royal names mentioned in this chapter:—

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD