Nineveh and Its Remains

Volume 2

By Austen Henry Layard, ESQ. D.C.L.

Part 2 - Chapter 2

IT has been assumed in the previous chapter that the language of the Assyrian inscriptions is a Semitic, or Syro-Arabian, dialect; but the question of what race the Assyrians were, may still be considered by some as open to doubt. It may be questioned, perhaps, whether we have sufficient knowledge of the inscriptions to decide, with certainty, the language of their contents. There are, however, as it has been shown, good grounds for believing that it is closely allied to the Chaldee; or, to use a term which has become familiar, that it is a branch of the Semitic. Such, it is generally admitted, is the language of the Babylonian column of the Persian trilingual inscriptions; which, it can be shown, contains the same formula? as the inscriptions of Assyria. For instance, the personal pronoun as used before the proper name of the king at Persepolis, is found precisely in the same position at Nimroud.1 We are aware, moreover, that the names of the Assyrian gods, as Baal, or Belus (the supreme deity amongst all the Semitic races), Nisroch, and Mylitta (known by a nearly similar name to the Arabians)2, of members of the family of the king, such as Adrameleck (son of Sennacherib), and of many of the principal officers of state mentioned in Scripture, such as Rab-saris, the chief of the eunuchs, and Rabshakeh, the chief of the cup-bearers, were purely Semitic.3 The language spoken by Abraham when he left Mesopotamia closely resembled the Hebrew; and his own name was Semitic.4 Moreover, a dialect of the same tongue is still spoken by the Chaldaeans of Kurdistan; who, there is good reason to suppose, are the descendants of the ancient Assyrians.5 There is something, at the same time, if I may so express myself, peculiarly Semitic in the genius and taste of the Assyrians, as displayed by their monuments. This is undoubtedly a mere conjecture; but the peculiar characteristics of the three great races which have, at different periods, held dominion over the East, cannot fail to strike every reflecting traveller. The distinctions between them are so marked, and are so fully illustrated even to this day, that they appear to be more than accidental — to be consequent upon certain laws, and to be traceable to certain physical causes. In the first place, there is the Shemite, whether Hebrew, Arab, or Syrian, with his brilliant imagination, his ready conception, and his repugnance to any restraint, that may affect the liberty of his person or of his intellect. He conceives naturally beautiful forms, whether they be embodied in his words or in his works; his poetry is distinguished by them, and they are shown even in the shape of his domestic utensils. This race possesses, in the highest degree, what we call imagination. The poor and ignorant Arab, whether of the desert or town, moulds with clay the jars for his daily wants, in a form which may be traced in the most elegant vases of Greece or Rome; and, what is no less remarkable, identical with that represented on monuments, raised by his ancestors, 3000 years before. If he speaks, he shows a ready eloquence; his words are glowing and apposite; his descriptions true, yet brilliant; his similes just, yet most fanciful. These high qualities seem to be innate in him; he takes no pains to cultivate, or to improve them: he knows nothing of reducing them to any rule, or measuring them by any standard. As it is with him, so it has been from time unknown with those who went before him: there has been little change — no progress. Look, on the other hand, at the so-called Indo-European races — at the Greek and Roman. They will adopt from others the most beautiful forms: it is doubtful whether they have invented any of themselves. But they seek the cause of that beauty; they reduce it to rules by analysis and reasoning; they add or take away — improve that which they have borrowed, or so change it in the process to which it is subjected, that it is no longer recognised as the same thing. That which appeared to be natural to the one, would seem to be the result of profound thought and inquiry in the other. Let the untaught man of this race model a vase, or address his fellows, he produces the rudest and most barbarous forms; or, whilst speaking roughly and without ease, makes use of the grossest images. We have next the Mongolian, whether Scyth, Turk, or Tatar — without imagination, or strong reasoning powers — intrepid in danger, steady in purpose, overcoming all opposition, despising his fellows, a great conqueror. Such has been his character as long as history has recorded his name: he appears to have been made to command and to oppress. We find him in the infancy of the human race, as well as at later periods, descending from his far distant mountains, emerging from the great deserts in central Asia, and overrunning the most wealthy, the most mighty, or the most civilised of nations. He exercises power as his peculiar privilege and right. The solitary Turkish governor rules over a whole province, whose inhabitants, whilst they hate him as an intruder and a barbarian, tremble at his nod. It is innate in his children — the boy of seven has all the dignity and self-confidence in rule, which characterises the man. The Mongolian must give way before the civilisation of Europe, with its inventions and resources; but who can tell whether the time may not come when he may again tread upon the other races, as he has done, at intervals, from the remotest ages? But observe the absence of all those intellectual qualities which have marked the Shemite and the Indo-European. If the Mongolian nations were to be swept from the face of the earth, they would leave scarcely a monument to record their former existence: they have had no literature, no laws, no art to which their name has attached. If they have raised edifices, they have servilely followed those who went before them, or those whom they conquered. They have depopulated, not peopled. Whether it be the Scythic invasion recorded by Herodotus, or the march of Timourleng, we have the same traces of blood, the same desert left behind; but no great monument, no great work. These may be but theories; yet the evidence afforded to this day, by the comparative state of the three races, is scarcely to be rejected. In no part of the world is the contrast, between the peculiar qualities of each, more strikingly illustrated than in the East, where the three are brought into immediate contact; forming, indeed mixed up together, yet still separate in blood, the population of the land. The facts are too palpable to escape the most casual observer; they are daily brought to the notice of those who dwell amongst the people; and whilst the Arab, the Greek, and the Turk, are to be at once recognised by their features, they are no less distinctly marked by their characters and dealings.6 But, to return from this digression, let us inquire whether the site of Nineveh is satisfactorily identified. That it was built on the eastern banks of the Tigris, there can be no doubt. Although Ctesias, and some who follow him, place it on the Euphrates, the united testimony of Scripture, of ancient geographers, and of tradition, most fully proves that that author, or an inaccurate transcriber or commentator of his text, has fallen into an error.7 Strabo says that the city stood between the Tigris and the Lycus, or Great Zab, near the junction of these rivers; and Ptolemy places it on the Lycus. This evidence alone is sufficient to fix its true position, and to identify the ruins of Nimroud. The tradition, placing the tomb of the prophet Jonah on the left bank of the river opposite Mosul, has led to the identification of the space comprised within the quadrangular mass of mounds, containing Kouyunjik and Nebbi Yunus, with the site of ancient Nineveh. These ruins, however, taken by themselves, occupy much too small a space to be those of a city, even larger, according to Strabo, than Babylon.8 Its dimensions, as given by Diodorus Siculus, were 150 stadia on the two longest sides of the quadrangle, and 90 on the opposite, the square being 480 stadia, or about 609 miles. In the book of Jonah, it is called " an exceeding great city of three days' journey,"10 the number of inhabitants, who did not know their right hand from their left, being six score thousand. I will not stop to inquire to what class of persons this number applied; whether to children, to those ignorant of right and wrong, or to the whole population.11 It is evident that the city was one of very considerable extent, and could not have been comprised in the space occupied by the ruins opposite Mosul, scarcely five miles in circumference. The dimensions of an eastern city do not bear the same proportion to its population, as those of an European city. A place as extensive as London, or Paris, might not contain one third of the number of inhabitants of either. The custom, prevalent from the earliest period in the East, of secluding women in apartments removed from those of the men12, renders a separate house for each family almost indispensable. It was probably as rare, in the time of the Assyrian monarchy, to find more than one family residing under one roof, unless composed of persons very intimately related, such as father and son, as it is at present in a Turkish city. Moreover, gardens and arable land were enclosed by the city walls. According to Diodorus and Quintus Curtius, there was space enough within the precincts of Babylon to cultivate corn for the sustenance of the whole population, in case of siege, besides gardens and orchards.13 From the expression of Jonah, that there was much cattle within the walls14, it may be inferred that there was also pasture for them. Many cities of the East, such as Damascus and Isphahan, are thus built; the amount of their population being greatly disproportionate to the site they occupy, if computed according to the rules applied to European cities. It is most probable that Nineveh and Babylon resembled them in this respect. The ruins hitherto examined have shown, that there are remains of buildings of various epochs, on the banks of the Tigris, near its junction with the Zab; and that many years, or even centuries, must have elapsed between the construction of the earliest and the latest. That the ruins at Nimroud were within the precincts of Nineveh, if they do not alone mark its site, appears to be proved by Strabo, and by Ptolemy's statement that the city was on the Lycus, corroborated by the tradition preserved by the earliest Arab geographers. Yakut, and others mention the ruins of Athur, near Selamiyah, which gave the name of Assyria to the province; and Ibn Said expressly states, that they were those of the city of the Assyrian kings who destroyed Jerusalem.15 They are still called, as it has been shown, both Athur and Nimroud. The evidence afforded by the examination of all the known ruins of Assyria, further identifies Nimroud with Nineveh. It would appear from existing monuments16, that the city was originally founded on the site now occupied by these mounds. From its immediate vicinity to the place of junction of two large rivers, the Tigris and the Zab, no better position could have been chosen. It is probable that the great edifice, in the north-west corner of the principal mound, was the temple or palace, or the two combined; the smaller houses were scattered around it. over the face of the country. To the palace was attached a park, or paradise as it was called, in which was preserved game of various kinds for the diversion of the king. This enclosure, formed by walls and towers, may perhaps still be traced in the line of low mounds branching out from the principal ruin. Future monarchs added to the first building, and the centre palace arose by its side. As the population increased with the duration and prosperity of the empire, and by the forced immigration of conquered nations, the dimensions of the city increased also. A king founding a new dynasty, or anxious to perpetuate his fame by the erection of a new building, may have chosen a distant site. The city, gradually spreading, may at length have embraced such additional palaces. This appears to have been the case with Nineveh. Nimroud represents the original site of the city. To the first palace the son of its founder added a second, of which we have the ruins in the centre of the mound. He also built the edifice now covered by the great mound of Baasheikha, as the inscriptions on the bricks from that place prove. He founded, at the same time, a new city at Kalah Sherghat. A subsequent monarch again added to the palaces at Nimroud, and recorded the event on the pavement slabs, in the upper chambers of the western face of the mound. At a much later period, when the older palaces were already in ruins, edifices were erected on the sites now marked by the mounds of Khorsabad, and Karamles. The son of their founder built the great palace at Kouyunjik, which must have exceeded those of his predecessors in extent and magnificence. His son was engaged in raising one more edifice at Nimroud; the previous palaces, as it has been shown, having been long before deserted or destroyed, when some great event, perhaps the fall of the empire and destruction of the capital, prevented its completion. The city had now attained the dimensions assigned to it by the book of Jonah, and by Diodorus Siculus. If we take the four great mounds of Nimroud, Kouyunjik, Khorsabad, and Karamles, as the corners of a square, it will be found that its four sides correspond pretty accurately with the 480 stadia or 60 miles of the geographer, which make the three days' journey of the prophet.17 Within this space there are many large mounds, including the principal ruins in Assyria, such as Karakush, Baasheikha, Baazani, Husseini, Tel-Yara, &c., &c.; and the face of the country is strewed with the remains of pottery, bricks, and other fragments. The space between the great public edifices was probably occupied by private houses, standing in the midst of gardens, and built at distances from one another; or forming streets which enclosed gardens of considerable extent, and even arable land. The absence of the remains of such buildings may easily be accounted for. They were constructed almost entirely of sun-dried bricks, and, like the houses now built in the country, soon disappeared altogether when once abandoned, and allowed to fall into decay. The largest palaces would probably have remained undiscovered, had there not been the slabs of alabaster to show the walls. There is, however, sufficient to indicate, that buildings were once spread over the space above described; for, besides the vast number of small mounds everywhere visible, scarcely a husbandman drives his plough over the soil, without exposing the vestiges of former habitations. Each quarter of the city may have had its distinct name; hence the palace of Evorita, where Saracus destroyed himself, and the Mespila and Larissa of Xenophon, applied respectively to the ruins at Kouyunjik and Nimroud.18 Existing ruins thus show, that Nineveh acquired its greatest extent in the time of the kings of the second dynasty; that is to say, of the kings mentioned in Scripture. It was then that Jonah visited it, and that reports of its size and magnificence were carried to the west, and gave rise to the traditions from which the Greek authors mainly derived the information handed down to us. I know of no other way, than that suggested, to identify all the ruins described in the previous pages with Nineveh; unless, indeed, we suppose that there was more than one city of the same name; and that, like Babylon, it was rebuilt on a new site, after having been once destroyed.19 In this case Nimroud, and Kouyunjik may represent cities of different periods, but of the same name; for, as I have shown, the palace of Kouyunjik must have been built long after the foundation of the Nineveh, of well-authenticated history. The position of Khorsabad, its distance from the river, and its size, preclude the idea that it marks alone the site of a large city. As the last palace at Nimroud must have been founded, whilst those at Kouyunjik and Khorsabad were standing, it is most probable that the city at that time embraced the remains of the old town, although the earlier buildings may have been destroyed. Having thus pointed out the evidence as to the site and extent of Nineveh, it may not be uninteresting to inquire how it was built, and what knowledge the Assyrians possessed of the science of architecture. The architecture of a people must naturally depend upon the materials afforded by the country, and upon the objects of their buildings. The descriptions, already casually given in the course of this work of the ruined edifices of ancient Assyria, are sufficient to show that they differ, in many respects, from those of any other nation with which we are acquainted. Had the Assyrians, so fertile in invention, so skilful in the arts, and so ambitious of great works, dwelt in a country as rich in stone and costly granites and marbles as Egypt or India, it can scarcely be doubted that they would have equalled, if not excelled, the inhabitants of those countries in the magnitude of their pyramids, and in the magnificence and symmetry of their rock temples and palaces. But their principal settlements were in the alluvial plains watered by the Tigris and Euphrates. On the banks of those great rivers, which spread fertility through the land, and afford the means of easy and expeditious intercourse between distant provinces, they founded their first cities. On all sides they had vast plains, unbroken by a single eminence until they, approached the foot of the Armenian hills. The earliest habitations, constructed when little progress had been made in the art of building, were probably but one story in height. In this respect the dwelling of the ruler scarcely differed from the meanest hut. It soon became necessary, however, that the temples of the gods, and the palaces of the kings, depositories at the same time of the national records, should be rendered more conspicuous than the humble edifices by which they were surrounded. The means of defence also required that the castle, the place of refuge for the inhabitants in times of danger, or the permanent residence of the garrison, should be raised above the city, and should be built so as to afford the best means of resistance to an enemy. As there were no natural eminences in the country, the inhabitants were compelled to construct artificial mounds. Hence the origin of those vast, solid, structures which have defied the hand of time; and, with their grass-covered summits and furrowed sides, rise like natural hills in the Assyrian plains.20 Let us picture to ourselves the migration of one of the primitive families of the human race, seeking for some spot favourable to a permanent settlement, where water abounded, and where the land, already productive without cultivation, promised an ample return to the labour of the husbandman. They may have followed him who went out of the land of Shinar, to found new habitations in the north21; or they may have descended from the mountains of Armenia; whence came, according to the Chaldaean historian, the builders of the cities of Assyria.22 It was not until they reached the banks of the great rivers, if they came from the high lands, or only whilst they followed their courses, if they journeyed from the south, that they could find a supply of water adequate to the permanent wants of a large community. The plain, bounded to the west and south by the Tigris and Zab, from its fertility, and from the ready means of irrigation afforded by two noble streams, may have been first chosen as a resting place; and there were laid the foundations of a city, destined to be the capital of the eastern world. The materials for building were at hand, and in their preparation required neither much labour nor ingenuity. The soil, an alluvial deposit, was rich and tenacious. The builders moistened it with water, and, adding a little chopped straw that it might be more firmly bound together, they formed it into squares, which, when dried by the heat of the sun, served them as bricks. In that climate the process required but two or three days. Such were the earliest building materials; and they are used to this day almost exclusively in the same country. This mode of brick- making is described by Sanchoniathon23; and we have an allusion to it in Exodus24; for the Egyptians, to harass their Jewish captives, withheld the straw without which their bricks could not preserve their form and consistency. Huts for the people were speedily raised, the branches and boughs of trees from the banks of the river serving for a roof. They now sought to build a place of refuge in case of attack, or an habitation for their leader, or a temple to their gods. It was first necessary to form an eminence, that the building might rise above the plain and might be seen from afar. This eminence was not hastily made by heaping up earth, but regularly and systematically built with sun-dried bricks. Thus a platform, thirty or forty feet high, was formed; and upon it they erected the royal, or sacred edifice.25 Sun-dried bricks were still the principal, but could not in this instance, for various reasons, be the only materials employed. The earliest edifices of this nature appear to have been at the same time public monuments, in which were preserved the records or archives of the nation, carved on stone. In them were represented in sculpture the exploits of the kings, or the forms of the divinities; whilst the history of the people, and invocations to their gods, were also inscribed in written characters upon the walls. It was necessary, therefore, to use some material upon which figures and inscriptions could be carved. The plains of Mesopotamia, as well as the low lands between the Tigris and the hill-country, abound in a kind of coarse alabaster or gypsum. Large masses of it everywhere protrude in low ridges from the alluvial soil, or are exposed in the gullies formed by winter torrents. It is easily worked, and its colour and transparent appearance are agreeable to the eye. Whilst offering few difficulties to the sculptor, it was an ornament to the edifices in which it was placed. This alabaster therefore, cut into large slabs, was used in the public buildings. The walls of the chambers, from five to fifteen feet thick, were first constructed of sun-dried bricks. The alabaster slabs were used as panels. They were placed upright against the walls, care being first taken to cut on the back of each an inscription recording the name, title, and descent of the king undertaking the work. They were kept in their places and held together by iron, copper, or wooden cramps and plugs. The cramps were in the form of double dovetails, and fitted into corresponding grooves in two adjoining slabs.26 The corners of the chambers were generally formed by one angular stone; arid all the walls were either at right angles, or parallel to each other. The slabs having been fixed against the walls, the subjects to be represented upon them were designed and sculptured, and the inscriptions carved. That the Assyrian artist worked after the slabs had been fixed, appears to be proved beyond a doubt, by figures and other parts of the bas-reliefs being frequently finished on the adjoining slab; and by slabs yet unsculptured being found, placed in one of the buildings at Nimroud.27 The principal entrances to the chambers were, it has been seen, formed by gigantic winged bulls and lions with human heads. The smaller doorways were guarded by colossal figures of divinities, or priests. No remains of doors or gates were discovered, nor of hinges; but it is probable that the entrances were provided with them. The priests of Babylon " made fast their temples with doors, with locks and bars, lest their gods be spoiled by robbers,"28 and the gates of brass of Babylon are continually mentioned by ancient authors. On all the slabs forming entrances, in the oldest palace of Nimroud, were marks of a black fluid, resembling blood, which appeared to have been daubed on the stone. I have not been able to ascertain the nature of this fluid; but its appearance cannot fail to call to mind the Jewish ceremony, of placing the blood of the sacrifice on the lintel of the doorway. Under the pavement slabs, at the entrances, were deposited small figures of the gods, probably as a protection to the building.29 Sometimes, as in the early edifices, tablets containing the name and title of the king, as a record of the time of the erection of the building, were buried in the walls, or under the pavement. The slabs used as a panelling to the walls of unbaked brick, rarely exceeded twelve feet in height; and in the earliest palace of Nimroud were generally little more than nine; whilst the human-headed lions arid bulls, forming the doorways, vary from ten to sixteen. Even these colossal figures did not complete the height of the room; the wall being carried some feet above them. This upper wall was built either of baked bricks, richly coloured, or of sundried bricks covered by a thin coat of plaster, on which were painted various ornaments. It could generally be distinguished in the ruins. The plaster which had fallen, was frequently preserved in the rubbish, arid when first found the colours upon it had lost little of their original freshness and brilliancy. It is to these upper walls that the complete covering up of the building, and the consequent preservation of the sculptures, may be attributed; for when once the edifice was deserted they fell in, and the unbaked bricks, again becoming earth, encased the whole ruin. The principal palace at Nimroud must have been buried in this manner, for the sculptures could not have been preserved as they were, had they been covered by a gradual accumulation of the soil. In this building I found several chambers without the panelling of alabaster slabs. The entire wall had been plastered and painted, and processions of figures were still to be traced. Many such walls exist to the east and south of the same edifice, and in the upper chambers.30 The roof was probably formed by beams, supported entirely by the walls; smaller beams, planks, or branches of trees, were laid across them, and the whole was plastered on the outside with mud. Such are the roofs in modern Arab cities of Assyria, It has been suggested that an arch or vault was thrown from wall to wall. Had this been the case, the remains of the vault, which must have been constructed of baked bricks or of stone, would have been found in the ruins, and would have partly filled up the chambers. No such remains were discovered.31 The narrowness of the chambers in all the Assyrian edifices, with the exception of one hall (Y, plan 3.) at Nimroud, is very remarkable. That hall may have been entirely open to the sky; and, as it did not contain sculptures, it is not improbable that it was so; but it can scarcely be conceived that the other chambers were thus exposed to the atmosphere, and their inmates left unprotected from the heat of the summer sun, or from the rains of winter. The great narrowness of all the rooms, when compared with their length, appears to prove that the Assyrians had no means of constructing a roof requiring other support than that afforded by the side walls. The most elaborately ornamented hall at Nimroud, although above 160 feet in length, was only 35 feet broad. The same disparity is apparent in the edifice at Kouyunjik.32 It can scarcely be doubted that there was some reason for making the rooms so narrow; otherwise proportions better suited to the magnificence of the decorations, the imposing nature of the colossal sculptures forming the entrances, and the length of the chambers, would have been chosen. But still, without some such artificial means of support as are adopted in modern architecture, it may be questioned whether beams could span 45, or even 35 feet. It is possible that the Assyrians were acquainted with the principle of the king-post of modern roofing, although in the sculptures the houses are represented with flat roofs: otherwise we must presume that wooden pillars or posts were employed; but there were no indications whatever of them in the ruins. Beams, supported by opposite walls, may have met in the centre of the ceiling. This may account for the great thickness of some of the partitions. Or in the larger halls a projecting ledge, sufficiently wide to afford shelter and shade, may have been carried round the sides, leaving the centre exposed to the air. Remains of beams were everywhere found at Nimroud, particularly under fallen slabs. The wood appeared to be entire, but when touched it crumbled into dust. It was only amongst the ruins in the south-west corner of the mound, that any was discovered in a sound state. The only trees within the limits of Assyria sufficiently large to furnish beams to span a room 30 or 40 feet wide, are the palm and the poplar: their trunks still form the roofs of houses of Mesopotamia. Both easily decay, and will not bear exposure; it is not surprising, therefore, that beams made of them should have entirely disappeared after the lapse of 2,500 years. The poplar now used at Mosul is floated down the Ehabour and Tigris from the Kurdish hills33; it is of considerable length, and occasionally serves for the roofs of chambers nearly as wide as those of the Assyrian palaces. It has been seen that the principle of the arch was known to the Assyrians34, a small vaulted chamber of baked bricks having been found at Nimroud; but there are no traces of an arch or vault used on a large scale. If daylight were admitted into the Assyrian palaces, it could only have entered from the roof. There are no communications between the inner rooms except by the doorways, consequently they could only receive light from above. Even in the chambers next to the outer walls, there are no traces of windows.35 It may be conjectured, therefore, that there were square openings or skylights in the ceilings, which may have been closed during winter rains by canvass, or some such material. The drains, leading from almost every chamber, would seem to show that water might occasionally have entered from above, and that apertures were required to carry it off. This mode of lighting rooms was adopted in Egypt; but, I believe, at a much later period than that of the erection of the Nimroud edifices. No other can have existed in the palaces of Assyria, unless, indeed, torches and lamps were used; a supposition scarcely in accordance with the elaborate nature of the sculptures, and the brilliancy of the coloured ornaments; which, without the light of day, would have lost half their effect. The pavement of the chambers was formed either of alabaster slabs, covered with inscriptions recording the name and genealogy of the king, and probably the chief events of his reign, or of kiln-burnt bricks, each also bearing a short inscription. The alabaster slabs were placed upon a thin coating of bitumen spread over the bottom of the chamber, even under the upright slabs forming its sides. The bricks were laid in two tiers, one above the other; a thin layer of sand being placed between them, as well as under the bottom tier. These strata of bitumen and sand may have been intended to exclude damp; although the buildings, from their position, could scarcely have been exposed to it. Between the lions and bulls forming the entrances, was generally placed one large slab, bearing an inscription. I have already alluded36 to the existence of a drain beneath almost every chamber in the older palace of Nimroud. These were connected with the floor by a circular pipe of baked clay, leading from a hole, generally cut through one of the pavement slabs, in a corner of the room. They joined one large drain, running under the great hall (Y, in plan 3.), and from thence into the river, which originally flowed at the foot of the mound. The interior of the Assyrian palace must have been as magnificent as imposing.37 I have led the reader through its ruins, and he may judge of the impression its halls were calculated to make upon the stranger who, in the days of old, entered for the first time the abode of the Assyrian kings. He was ushered in through the portal guarded by the colossal lions or bulls of white alabaster.38 In the first hall he found himself surrounded by the sculptured records of the empire. Battles, sieges, triumphs, the exploits of the chace, the ceremonies of religion, were portrayed on the walls, sculptured in alabaster, and painted in gorgeous colours. Under each picture were engraved, in characters filled up with bright copper, inscriptions describing the scenes represented. Above the sculptures were painted other events — the king, attended by his eunuchs and warriors, receiving his prisoners, entering into alliances with other monarchs, or performing some sacred duty. These representations were enclosed in coloured borders, of elaborate and elegant design. The emblematic tree, winged bulls, and monstrous animals were conspicuous amongst the ornaments. At the upper end of the hall was the colossal figure of the kino; in adoration before the supreme deity, or receiving from his eunuch the holy cup. He was attended by warriors bearing his arms, and by the priests or presiding divinities. His robes, and those of his followers, were adorned with groups of figures, animals, and flowers, all painted with brilliant colours. The stranger trod upon alabaster slabs, each bearing an inscription, recording the titles, genealogy, and achievements of the great king. Several doorways, formed by gigantic winged lions or bulls, or by the figures of guardian deities, led into other apartments, which again opened into more distant halls. In each were new sculptures. On the walls of some were processions of colossal figures — armed men and eunuchs following the king, warriors laden with spoil, leading prisoners, or bearing presents and offerings to the gods. On the walls of others were portrayed the winged priests, or presiding divinities, standing before the sacred trees. The ceilings above him were divided into square compartments, painted with flowers, or with the figures of animals. Some were inlaid with ivory, each compartment being surrounded by elegant borders and mouldings. The beams, as well as the sides of the chambers, may have been gilded, or even plated, with gold arid silver; and the rarest woods, in which the cedar was conspicuous, were used for the wood-work.39 Square openings in the ceilings of the chambers admitted the light of day. A pleasing shadow was thrown over the sculptured walls, and gave a majestic expression to the human features of the colossal forms which guarded the entrances. Through these apertures was seen the bright blue of an eastern sky, enclosed in a frame on which were painted, in vivid colours, the winged circle, in the midst of elegant ornaments, and the graceful forms of ideal animals.40 These edifices, as it has been shown, were great national monuments, upon the walls of which were represented in sculpture, or inscribed in alphabetic characters, the chronicles of the empire. He who entered them might thus read the history, and learn the glory and triumphs of the nation. They served, at the same time, to bring continually to the remembrance of those who assembled within them on festive occasions, or for the celebration of religious ceremonies, the deeds of their ancestors, and the power and majesty of their gods. It would appear that the events recorded in the buildings hitherto examined, apply only to the kings who founded them. Thus, in the earliest palace of Nimroud, we find one name constantly repeated; the same at Kouyunjik and Khorsabad. In some edifices, as at Kouyunjik, each chamber is reserved for some particular historical incident; thus, on the walls of one, we find the conquest of a people residing on the banks of two rivers, clothed with groves of palms, the trees and rivers being repeated in almost every bas-relief. On those of a second is represented a country watered by one river, and thickly wooded with the oak or some other tree. In the bas-reliefs of a third we have lofty mountains, their summits covered with firs, and their sides with oaks and vines. In every chamber the scene appears to be different. It was customary in the later Assyrian monuments to write, over the sculptured representation of a captured city, its name, always preceded by a determinative letter or sign.41 Short inscriptions were also generally placed above the head of the king in the palace at Kouyunjik, preceded by some words apparently signifying " this is," and followed by others giving his name and title. The whole legend probably ran, "This is such an one (the name), the king of the country of Assyria." At Khorsabad similar short inscriptions are frequently found above less important figures, or upon their robes; a practice which, it has been seen, prevailed afterwards amongst the Persians,42 I may observe, that in the earliest palace of Nimroud, such descriptive notices have never been found introduced into the bas-reliefs. Were these magnificent mansions palaces or temples? or, whilst the king combined the character of a temporal ruler with that of a high-priest or type of the religion of the people, did his residence unite the palace, the temple, and a national monument raised to perpetuate the triumphs and conquests of the nation? These are questions which cannot yet be satisfactorily answered. We can only judge by analogy. The religious character of the king is evident from a very casual examination of the sculptures. The priests or presiding deities (whichever the winged figures so frequently found on the Assyrian monuments may be) are represented as waiting upon, or ministering to, him; above his head are the emblems of the divinity — the winged figure within the circle, the sun, the moon, and the planets. As in Egypt, he may have been regarded as the representative, on earth, of the deity; receiving his power directly from the gods, and the organ of communication between them and his subjects.43 All the edifices hitherto discovered in Assyria, have precisely the same character; so that we have most probably the palace and temple combined; for in them the deeds of the king, and of the nation, are united with religious symbols, and with the statues of the gods. Of the exterior architecture of these edifices, no traces remain. I examined as carefully as I was able the sides of the great mound at Nimroud, and of other ruins in Assyria; but there were no fragments of sculptured blocks, cornices, columns, or other architectural ornaments, to afford any clue to the nature of the façade. It is probable that as the building was raised on a lofty platform, and was conspicuous from all parts of the surrounding country, its exterior walls were either cased with sculptured slabs or painted. This mode of decorating public buildings appears to have prevailed in Assyria. On the outside of the principal palace of Babylon, built by Semiramis, were painted, on bricks, men and animals; even on the towers were hunting scenes, in which were distinguished Semiramis herself on horseback, throwing a javelin at a panther, and Ninus slaying a lion with his lance.44 The walls of Ecbatana, according to Herodotus45, were also painted in different colours. The largest of these walls (there were seven round the city) was white, the next was black, the third purple, the fourth blue, the fifth orange. The two inner walls were differently ornamented, one having its battlements plated with silver, the other with gold.46 At Khorsabad a series of alabaster slabs, on which were represented gigantic figures bearing tribute, appeared to M. Botta to be an outer wall, as there were no remains of building beyond it. It is possible that the sculptures on the edge of the ravine in the north-west palace of Nimroud, also apparently captives bearing tribute, may have formed part of the north fa9ade of the building, opening upon a flight of steps, or upon a road leading from the river to the great hall.47 We may conjecture, therefore, that the outer walls, like the inner, were cased with sculptured slabs below, and painted with figures of animals and other devices above; and thus ornamented, in the clear atmosphere of Assyria, their appearance would be far from unpleasing to the eye. They were probably protected by a projecting roof; and, in a dry climate, they would not quickly suffer injury from mere exposure to the air. The total disappearance of the alabaster slabs, may be easily accounted for by their position. They would probably have remained outside the building, when the interior was buried; or they may have fallen to the foot of the mound, where they soon perished, or where they may perhaps still exist under the accumulated rubbish.48 On the western face of the mound of Nimroud, at the foot, I discovered many large square stones, which probably cased the lower part of the building, or rather of the mound itself. Xenophon, describing the ruins, says that the lower part of the walls was of stone to the height of 20 feet; the upper being of brick.49 The stones he saw were merely the casing, the interior or body of the walls being built of sundried bricks. Although there were houses in Assyria of two and three stories in height, as at Babylon50, and as represented in the sculptures of Kouyunjik51, yet it does not appear probable that the great buildings just described, had more than a ground floor. If there had been upper rooms, traces of them would still be found, as is shown by the discovery of the chambers on the western face of the mound.52 Had they fallen in, some remains of them would have been left in the lower rooms. The houses, and towers represented in some of the later sculptures, have windows and doors ornamented with cornices. We have no means of ascertaining the forms of the chambers, nor of learning any particulars concerning their internal economy and arrangement. No private houses, either of Assyria Proper or Babylonia, have been preserved. The complete disappearance of private dwellings, as it has been shown, is mainly to be attributed to the perishable materials of which they were constructed. The mud-built walls returned to dust as soon as exposed, without occasional repair, to the effects of the weather — to rain, the heat of the sun, or hot winds. The traveller in Assyria may still observe the rapid decay of such edifices. He may search in vain for the site of a once flourishing village a few years after it has been abandoned. It would appear from the Assyrian sculptures that tents were in common use, even within the walls of a city. There are frequent representations of enclosures, formed by regular ramparts and fortifications, partly occupied by such habitations, in which are seen men, and articles of furniture, couches, chairs, and tables.

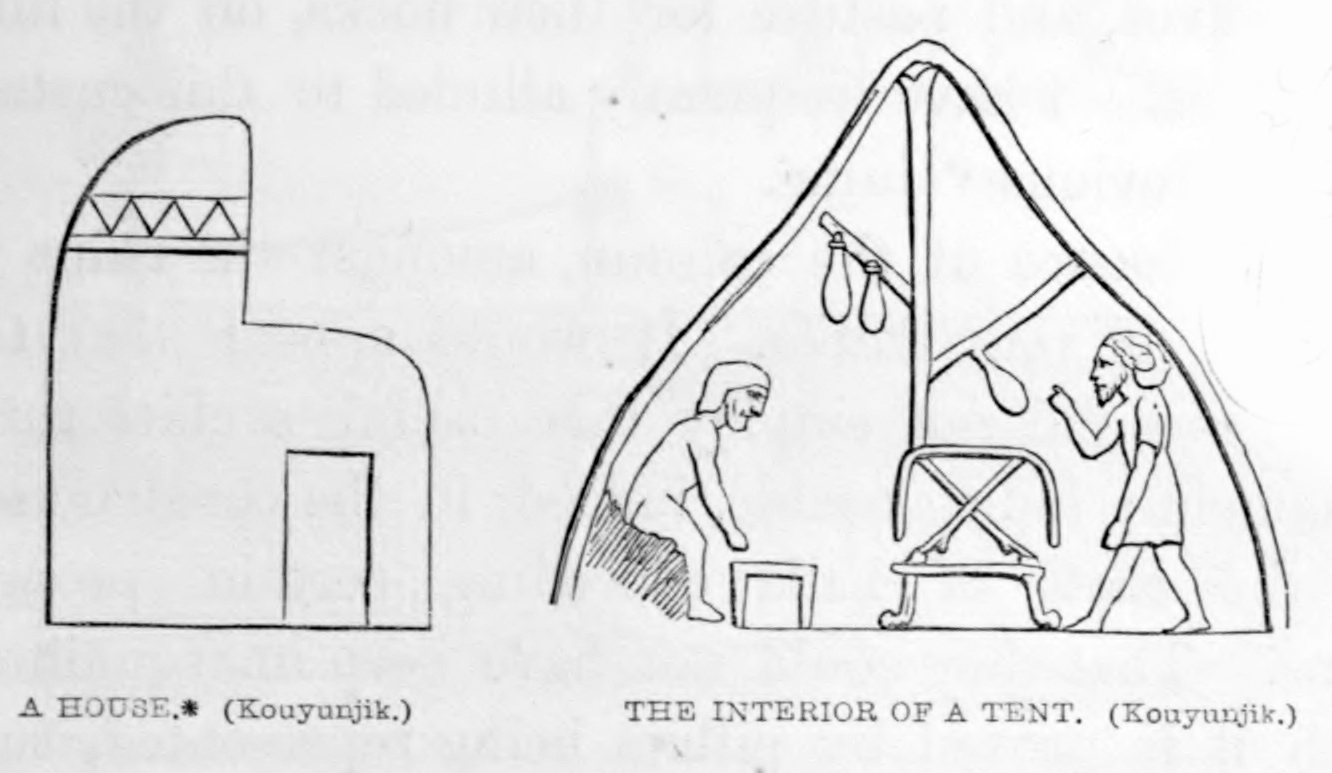

In the tent represented in the woodcut, jars appear to be suspended to the poles, to cool the water within. Such is now the practice in the East. It is still not an uncommon custom, in the countries included in ancient Assyria and Babylonia, for wandering tribes to encamp at certain seasons of the year within the walls of cities. In Baghdad, Mosul, and the neighbouring towns, the tents of Arabs and Kurds are frequently seen amongst the houses; and such it would appear was the case in Assyria in the earliest ages. Abraham, and Lot, resided in tents in the midst of cities. Lot had his house in Sodom, as well as his tents. We find continual mention of persons having tents, and living within walls at the same time.54 In the districts around Mosul, the inhabitants of a village frequently leave their houses during the spring, and seek a more salubrious air for themselves, and pasture for their flocks, on the hills or plains. I have frequently alluded to this custom in the previous volume. The absence of the column, amongst the ruins of Assyria, is remarkable. It would appear that the Assyrians did not employ this useful architectural ornament; indispensable, indeed, in the construction of the roofs of halls exceeding certain proportions. That they could not have been unacquainted with it is proved by pillars being represented, supporting a pavilion or tent, in the older sculptures of Nimroud. They were probably of wood, appear to have been painted, and were surmounted by a pine or fir cone, that religious symbol so constantly recurring in the Assyrian monuments.55 But the first indication of the use of columns in buildings, is to be found in the sculptures of Khorsabad. In a bas-relief from that ruin, a temple, fishing pavilion, or some building of the kind, is seen standing on the margin, or actually in the midst of, a lake or river. The façade is embellished by two columns, the capitals of which so closely resemble the Ionic, that we can scarcely hesitate to recognise in them the prototype of that order.56

In a bas-relief at Kouyunjik, the entrance to a castle was flanked by two similar columns. The city represented, appeared to belong to a maritime people inhabiting the shores of the Mediterranean, and may perhaps be identified (as it will hereafter be shown) with Tyre or Sidon. We have therefore the Ionic column on monuments of the eighth, or seventh, century before Christ. It is remarkable that the column, which appears thus to have been known to the Assyrians, was not used generally in their buildings. That it was not, unless merely of wood, appears to be proved by the absence of all remains of shafts and capitals; and in Eastern ruins these are the last things to disappear. The narrowness of the chambers, also, as I have observed, must be attributed to the want of means of supporting a ceiling, exceeding in width the span of an ordinary poplar or palm beam. It is possible that a conventional architecture, invested, as in Egypt, with a religious character, was introduced before the knowledge of the column. Hence, at a subsequent period, when this useful ornament was otherwise in common use, it was not admitted into sacred buildings. But. as far as I am aware, no remains of the column, which cannot be distinctly referred to a period subsequent to the Greek occupation, have yet been found in Assyria.57 The walls of the Assyrian cities, as we learn from the united testimony of ancient authors, were of extraordinary size and height. Their dimensions, as given by Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus, have every appearance of great exaggeration; but, from the remains which still exist, it is highly probable that they exceeded in thickness any modern walls. The materials were generally bricks of clay, dried in the sun. The inhabitants could thus raise their defences rapidly, without either great toil, or the cost and labour of transport from distant places. As the earth was removed to make the bricks, a ditch was formed round the walls; at least such, we are informed, was the case at Babylon. Sometimes the walls were constructed of these bricks alone. They were even then probably of sufficient strength to resist a siege. Frequently, however, this earthen rampart was cased with stones or slabs, carefully squared and adjusted; so that those who were unacquainted with the mode in which the walls were built, believed them to be entirely of stone. Sometimes the lower part only may have been cased with stone, the upper being entirely of brick; as, according to Xenophon, were the walls of Mespila and Larissa.58 According to Diodorus Siculus the walls of Nineveh were one hundred feet high, and so broad that three chariots might be driven abreast upon them. They were furnished with fifteen hundred towers, each two hundred feet in height. Those of Babylon, according to Herodotus, were two hundred cubits (or about three hundred feet) high, and fifty cubits (or about seventy-five feet) thick.59 In the Book of Judith the walls of Ecbatana are stated to have been seventy cubits in height, and fifty broad, or corresponding in thickness with those of Babylon. They were built of hewn stones, six cubits long and three broad; and the gates, " for the going forth of the mighty armies (of Nebuchadnezzar) and for the setting in array of the footmen," were severity cubits high and forty wide.60 Of these enormous structures, allowing for exaggeration, and inaccuracy, in the statements of the Greek historians61, there are still certain traces. They do not, however, enclose the space attributed to either Babylon or Nineveh, but form quadrangular enclosures of more moderate dimensions, which appear to have been attached to the royal dwellings, or were perhaps intended as places of refuge in case of siege. Such are the remains of Nimroud, Kouyunjik, and Khorsabad; and those on the left bank of the river Euphrates, near Hillah, the site of the Babylon of Nebuchadnezzar. These walls are now marked by consecutive mounds, having the appearance of ramparts of earth hastily thrown up. On examination, however, they are found to be regularly constructed of unbaked bricks. In height they have, of course, greatly decreased, and are still gradually decreasing, but the breadth of their base proves their former magnitude; and that they were of great strength, and able to resist the engines of war then in use, we learn from the fact that Nineveh sustained a siege for nearly three years in the time of Sardanapalus, and could only be taken by the combined armies of the Persians and Babylonians -when the river had overflowed its bed, and had carried away a part of the wall. According to Xenophon, Larissa was captured during the consternation of the inhabitants caused by an eclipse of the sun. At certain distances in the walls there were gates, sometimes flanked, as at Kouyunjik, by towers adorned with sculptures, and sometimes formed by gigantic figures, such as the winged bulls and lions. An entrance of this kind has recently been by chance exposed to view, in the mounds forming the quadrangle at Khorsabad. The lofty pyramidical structures, which still exist at Nimroud, Kalah Sherghat, and Khorsabad, may have been used, as it has been already observed, as watch-towers. In the edifices of Nineveh, bitumen and reeds were not employed to cement the layers of bricks, as at Babylon; although both materials are to be found in abundance in the immediate vicinity of the city.62 The Assyrians appear to have made much less use of bricks baked in the furnace than the Babylonians; no masses of brickwork, such as are everywhere found in Babylonia Proper, existing to the north of that province. Common clay moistened with water, and mixed with a little stubble, formed, as it does to this day, the mortar used in buildings. But, however simple the materials, they have successfully resisted the ravages of time, and still mark the stupendous nature of the Assyrian structures.

|

|

|

|

|

1) Thus

2) Viz. Alitta, Herod, lib. i. c. 131. 3) It is, however, possible that these may be mere Hebrew translations of Assyrian titles. An argument has been founded on the 26th verse of the 18th chapter of 2nd Kings. Eliakim says to the officers of the Assyrian king — " Speak, I pray thee, to thy servants in the Syrian language; for we understand it." From this passage it has been inferred that the language of the Assyrians was similar to that which prevailed in Syria, and consequently a Semitic dialect. 4) The name of Mesopotamia on the Egyptian monuments is Naharaina, i. e. the country between the two rivers. This is not only a pure Semitic word, but has a Semitic plural form. We may infer, therefore, that the people inhabiting that district, at least, were of Semitic origin. The Hebrew name of Mesopotamia was Aram Naharaim. 5) The question of the origin of the Chaldseans, the Casdim of Scripture, has been the subject of much discussion of late years. I confess that after carefully examining the arguments in favour of their Scythic and Indo-European descent, I see no reason to doubt the old opinion, that they were a Semitic or Syro- Arabian people. The German philologists were the first to question their Semitic origin. Michaelis made them Scyths; Schloezer, Sclavonians. According to Dicasarchus, a disciple of Aristotle, and a philosopher of great reputation, they were first called Cephenes from Cepheus, and afterwards Chaldaeans from Chaldaeus, an Assyrian king, fourteenth in succession from Ninus; this Chaldaeus built Babylon near the Euphrates, and placed the Chaldaeans in it. (Stephanus, Diet. Hist. Geog.) This appears to confirm the passage in Isaiah, which has chiefly given rise to the question as to the origin of the Chaldees. " Behold the land of the Chaldaeans; this people was not, till the Assyrian founded it for them that dwelt in the wilderness: they set up the towers thereof, they raised up the palaces thereof." (Ch. xxiii. v. 13.) The use of the term Chaldaean, like that of Assyrian, was very vague. It appears to have been applied at different periods to the entire country watered by the rivers Tigris and Euphrates, south of the mountainous regions of Armenia, to only a part of it, to a race, and ultimately to a class of the priesthood. That the Chaldees were at a very early period settled in cities, we learn from Genesis (ch. xi. v. 31.), for Abraham came from Ur of the Chaldees; but the position of Ur, whether to the north or south of Nineveh, whether Edessa (the modern Orfah) or Orchoe, or any other city whose geographical position can be conjectured, is still a disputed question, which is not likely to be soon, if ever, settled. It is right to observe, however, that the name may be a gloss of a later version of Genesis, a substitution, after the captivity, for the name of some obsolete city. The passage i n Judith (chap. v. ver. 6. & 7.), in which the Jews are spoken of as descendants of the Chaldajans, is remarkable. 6) Dr. Pritchard, in his valuable and learned " Researches into the Physical History of Mankind," has pointed out the peculiar characteristics of one of these great branches of the human race. " The Syro- Arabian nations," he observes, " are amongst the races of men who display the most perfect physical organisation. A well-known modern writer, who has had extensive opportunities of research into the anatomical and other corporeal characters of various nations, has maintained that the bodily fabric belonging to the Syro- Arabian tribes, manifests even a more perfect development in the organic structure, subservient to the mental faculties, than that which is found in other branches of the human family. It is certain that the intellectual powers of the Syro- Arabian people have, in all ages, equalled the highest standard of the human faculties." (Vol. iv. p. 548.) And again: " It is remarkable that the three great systems of theism which have divided the civilised world, came forth from nations of Shemite origin, among whom arose the priests or prophets of all those nations, who hold the unity of God." (Vol. iv. p. 549.) If this be true of the Syro-Arabian or Shemite races, we may, without inconsistency, seek for similar characteristics in the other branches of the human family; and I believe that a careful examination of the subject will show, that the history and condition of the three great races, justify the remarks in the text. 7) Herodotus, 1. i c. 193. and 1. ii. c. 150.; Pliny, lib. xvi. c. 13.; Strabo, 1. xvi.; Ammianus Marcell. 1. xxiii. c. 20. 8) Strabo, lib. xvi. 9) Or, according to some computations, 74 miles. 10) Chap. iii. ver. 3. 11) The numbers of Jonah have frequently been referred to children, who are computed to form one fifth of the population; thus giving six hundred thousand inhabitants for the city. 12) We learn from the book of Esther that such was the custom amongst the early Persians, although the intercourse between women and men was much less circumscribed than after the spread of Mohammedanism. Ladies were even admitted to public banquets, and received strangers in their own apartments, whilst they resided habitually in a kind of harem, separate from the dwellings of the men. 13) Diod. Sic. lib. ii. c. 9. Quintus Curtius, v. cap. 1.: "Ac ne totam quidem urbcm tectis occupaverunt; per xc. stadia habitatur: nee omnia continua sunt: credo quia tutius visum est, plurimis locis spargi; cetera scrunt coluntque, ut, si externa vis ingruat, obsessis alimenta, ex i urbis, solo subministrentur." 14) Chap. iv. ver. 11. 15) Yakut, in bis geographical work called the Moejem el Buldan, says, under the head of " Athur," " Mosul, before it received its present name, was called Athur, or sometimes Akur, with a kaf. It is said that this was anciently the name of el Jezireh (Mesopotamia), the province being so called from a city, of which the ruins are now to be seen naar the gate of Selamiyah, a small town, about eight farsakhs east of Mosul; God, however, knows the truth." The same notice of the ruined city of Athur, or Akur, occurs under the head of " Selamiyah." Abulfcda says, " To the south of Mosul, the lesser (?) Zab flows into the Tigris, near the ruined city of Athur." In Reinaud's edition (vol. i. p. 289. note 11.) there is the following extract from Ibn Said: — "The city of Athur, which is in ruins, is mentioned in the Taurat (Old Testament). There dwelt the Assyrian kings who destroyed Jerusalem." I am indebted for these notices to Major Rawlinson. 16) See previous chapter as to the identification of the names and genealoies of kins. 17) From the northern extremity of Kouyunjik to Nimroud, is about eighteen miles; the distance from Nimroud to Karamles, about twelve; the opposite sides of the square the same: these measurements correspond accurately with the elongated quadrangle of Diodorus. Twenty miles is the day's journey of the East, and we have consequently the three days' journey of Jonah for the circumference of the city. The agreement of these measurements is remarkable. Within this space was fought the great battle between Heraclius and Rhazates (A. D. 627). " The city, and even the ruins of the city, had long since disappeared: the vacant space afforded a spacious field for the operations of the two armies." (Gibbon, Decline and Fall, ch. xlvi.) 18) I have already shown that the account given by Xenophon of Larissa, as well as the distance between it and Mespila, agree in all respects with the ruins of Nimroud, and their distance from Kouyunjik. (Vol. I. p. 4.) The circuit of the walls of Larissa, two parasangs, also nearly coincides with the extent of the quadrangle at Nimroud 19) The attempt to identify Larissa and Nimroud with Resen, will, I presume, be now renounced. 20) The custom of erecting an artificial platform, and building an edifice on the summit, existed amongst the Mexicans, although they inhabited a hilly country. 21) Genesis, x. 11. 22) Xithurus and his followers. Berosus, apud Euseb. The similarity between the history of this Chaldaean hero and that of the Noah of Scripture is very singular. 23) According to Sanchoniathon (Cory's Fragments), the people of Tyre invented the art of brick-making, and of building huts. " Hypouranius," he says, " invented in Tyre the making of huts of reeds and rushes, and the papyri. After the generation of Ilypouranius were Agreus and Hsilieus, inventors of the arts of hunting and of fishing. After them came two brothers; one of them, Chrysor or Hyphaestus, was the first who sailed in boats; his brother invented the way of making walls with bricks. From this generation were born two youths, one called Technites, and the other Genius Autochthon. They discovered the method of mingling stubble with the loam of the bricks, and drying them in the sun; they also invented tiling." 24) Chap. v. 25) Such is the custom still existing amongst the inhabitants of Assyria. When some families of a nomad tribe wish to settle in a village, they choose an ancient mound; it being no longer necessary to form a new platform, for the old abound in the plains. On its summit they erect a rude castle, and the huts are built at the foot. This course appears to have been followed since the Arab invasion, and perhaps long previous, during the Persian occupation. There are few ancient mounds containing Assyrian ruins which have not served for the sites of castles, cities, or villages built by Persians or Arabs. Such are Arbela, Tel Afer, Nebbi Yunus, &c. &c. 26) Every slab has this groove of a dovetail shape on the edges; but there were besides three round holes at equal distances between them. I am unable to account for their use — whether to receive plugs which were in some way connected with the superstructure, or rods of metal which may have extended through the wall to the slab in the adjoining chamber. Only one of the dovetails (of iron) remained in its place. These cramps appear to have been used (according to Diodorus Siculus) at Babylon; the stones of the bridge, said to have been built by Semiramis, being united by them. Herodotus (lib. i. c. 186.) also states that the stones of the bridge built over the Euphrates by Nitocris were joined by iron and lead. Similar cramps made of lead and wood, inscribed with the name of the king, are found in Egyptian buildings as early as the XVII — XIX dynasty. 27) This mode of sculpturing the stone after placing it appears to have been generally the custom in Egypt and India. 28) Epistle of Jeremy. Baruch, vi. 18. 29) It has already been mentioned, that these small figures in unbaked clay, were found beneath the pavement in all the entrances at Khorsabad. They were only discovered at Nimroud in the most recent palace, in the south-west corner of the mound. See p. 37. of this volume. M. Botta conjectures that the copper lion, discovered at Khorsabad between the bulls forming the entrance, was chained to the large sculptures by a chain of copper or bronze, fastened to the ring on the back of the animal. But the size of the smallest of those found at Nimroud (Vol. I. p. 128.) seems to preclude this supposition. It is remarkable, however, that almost every slab forming an entrance has a hole in the centre, as if intended for a ring or bolt. 30) Plan 4. p. 14. of this volume. 31) M. Flandin (Voyage Archéologique à Ninive, in the Revue des Deux Mondes) states that he found sufficiently large masses of kiln-burnt bricks in the chambers at Khorsabad, to warrant the supposition that the roof had been vaulted with them. But I am inclined to doubt this having been the case; and I believe M. Botta to be of my opinion. 32) Some of the chambers at Kouyunjik were about 45 feet wide. 33) Vol. I. p. 167. 34) Arched gateways are continually represented in the bas-reliefs. According to Diodorus Siculus, the tunnel under the Euphrates at Babylon, attributed to Semiramis, was also vaulted. Indeed, if such a work ever existed, it may be presumed that it was so constructed. It was cased on both sides, that is, the bricks were covered, with bitumen; the walls were four cubits thick. The width of the passage was 15 feet; and the walls were 12 feet high to the spring of the vault. The rooms in the temple of Belus were, according to some, arched and supported by columns. The arch first appears in Egypt about the time of the commencement of the eighteenth dynasty (Wilkinson's Ancient Egyptians, vol. ii. p. 117.), or when, as it has been shown, there existed a close connection between Egypt and Assyria. 35) It is possible that some of the chambers, particularly if devoted to religious purposes, were only lighted by torches, or by fires fed by bitumen or naphtha. This custom appears to be alluded to in the Epistle of Jeremy. " Their faces are blackened through the smoke that cometh out of the temple." (Baruch, vi. 21.) But no traces of smoke or fire were found on the sculptures and walls of the earliest palace of Nimroud. 36) P. 79. of this volume. 37) According to Moses of Chorene (lib. i.), the palaces in Armenia at the earliest period were built by Assyrian workmen, who had already attained to great skill in architecture. The Armenians thus looked traditionally to Assyria for the origin of some of their arts. 38) In the palace of Scylas in the city of the Borysthenitn?, against which Bacchus hurled his thunder-bolt, were placed sphinxes and gryphons of white marble. (Herod, lib. iv. c. 79.) 39) Sun-dried bricks, with the remains of gilding, were discovered at Nimroud. Herodotus states that the battlements of the innermost walls of the royal palace of Ecbatana, the ornaments of which were most probably imitated from the edifices of Assyria, were plated with silver and gold (lib. i. c. 98.); and the use of gold in the decorations of the palaces of the East is frequently mentioned in ancient authors. Even the roofs of the palace at Ecbatana are said to have been covered with silver tiles. The gold, silver, ivory, and precious woods in the roofs of the palaces of Babylon, attributed to Semiramis, are frequently mentioned by ancient writers. Thus, in the Periegesis of Dionysius, v. 1005 — 1008. —

Translated by Priscian, v. 950 — 953. —

And by Rufus Festus Avienus (Orbis Descriptio, v. 1196 — 1201.) —

Zephaniah (xi. 14.) alludes to the "cedar work" of the roof; and in Jeremiah (xxii. 14.) chambers "ceiled with cedar and painted with vermilion" are mentioned. It is probable that the ceilings were only panelled or wainscotted with this precious wood. (1 Kings, vi. 15., vii. 3.) The ceilings of Egyptian tombs and houses were like those described in the text. (Wilkinson's Ancient Egyptians, vol. ii. p. 125.) The ivory ornaments found in some of the chambers at Nimroud may possibly have belonged to the ceiling. 40) I have endeavoured, with the assistance of Mr. Owen Jones, to give, in my work on the Monuments of Nineveh, a representation of a chamber or hall as it originally appeared. I have restored the details from fragments found during the excavations, and from parts of the building still standing. There is full authority for all except the ceiling, which must remain a subject of conjecture. The window or opening in it has been placed immediately above the winged lions, to bring it into the plate; but it is probable that it was in the centre of the hall. The larger chambers may have had more than one such opening. 41) This sign, which I have given, in note, p. 192., appears to be the first letter of a word signifying city or castle, or to be a monogram for the word. Dr. Hincks traces in it a rude representation of a rampart and parapet, (On the Inscriptions of Van, p. 29.) 42) On the great rock-tablet of Behistun we have not only the name and genealogy of Darius written over his head, but also the name and country of the prisoners placed above each. 43) Diodorus Siculus, lib. i. c. 90., and Wilkinson's Ancient Egyptians, vol. i. p. 245., and vol. ii. p. 67. 44) Diodorus Siculus, lib. ii. 45) Lib. i. c. 98. 46) These colours, with the number seven of the walls, have evidently allusion to the planets, and their courses. (Herod. 1. 1. c. 98.) Seven disks are frequently represented as accompanying the sun, moon, and other religious emblems at Nimroud. 47) D and E, plan 3., and see Vol. I. p. 125. 48) The thickness of both the outer walls and the walls forming partitions between the chambers, may have contributed greatly to exclude the heat and to keep the chambers cool. It was Mr. Longworth's impression, on examining the ruins, that there never had been any exterior architecture, but that all the chambers had been, as it were, subterranean, resembling the serdabs, or summer apartments, of Mosul and Baghdad. But such a supposition does not appear to me consistent with the magnificent entrances, and with the elevated position of the building. Had underground apartments been contemplated, an artificial platform would scarcely have been raised to receive them. 49) Anab. lib. iii. c. iv. s. 7. 50) Herod, lib. i. c. 180. 51) At Nimroud, although there were towers represented in the bas-reliefs, with windows evidently belonging to the upper stories, yet there were no houses of two stories. 52) See p. 14. of this volume. 53) This house appears to resemble the model of an Egyptian dwelling in the British Museum. (See also Sir Gardner Wilkinson's Ancient Egyptians, vol. ii. woodcuts 98 and 99.) From a bas-relief discovered in the centre of the mound at Nimroud, it would appear that the upper part was sometimes formed of canvass. 54) These tents were probably made of black goat-hair, like those of the modern Arabs — " I am black, but comely, O ye daughters of Jerusalem, as the tents of Kedar" (Cant. i. 5.) — and were not the gay white pavilions which are usually seen in modern Biblical illustrations. 55) An engraving from a bas-relief, showing such columns, will be included in my work on the Monuments of Nineveh; and the bas-relief itself will be placed in the British Museum. 56) On an ivory tablet from Nimroud, the capitals of pillars, supporting a kind of frame enclosing a head, also nearly resemble the Ionic; but less so than those given in the woodcut. They have, however, the egg and tongue ornament under the helices. The lower part of the pine or fir cone, surmounting the columns of wood described in the previous page, has also much the appearance of the volute of the Ionic. 57) Nor have any been found, I believe, amongst the ruins of Babylon. 58) Cyrop. lib. iii. The lower part of the walls of Mespila, according to Xenophon, was fifty feet high, and as many broad, and the upper one hundred high. The plinth was of a polished stone full of shells — the limestone still abounding in the country. The base of the walls is frequently the common river conglomerate. There are no remains at Kouyunjik to show that any part of the wall was of solid stone; yet there can scarcely be a doubt that Mespila is represented by the ruins opposite Mosul. Nor does the circuit of six parasangs, mentioned by Xenophon, agree with the present dimensions, which do not amount to as many miles. Some allowance must be made for a little exaggeration. 59) The walls of Babylon formed one of the standard fables of the ancients. According to some they were of brass. The Greek scholiast, upon the passage in the Periegesis of Dionysius (quoted p. 262.), says: — " To the south (of the Matieni) lies the great city of Babylon, which Semiramis crowned with unbreakable, brazen or strong, walls; for the wall is said to be brazen, for it was on every side flanked by the river." Eustathius, commenting on the same passage of Dionysius, observes: — " In the south of Mesopotamia is Babylon, the Persian metropolis, a sacred city surrounded with a brazen wall according to some, and with a river flowing round it; all of which, he says, Semiramis crowned with unbreakable walls. Where some, forsooth, as it has been said, have narrated that the wall was of brass, and have put forth many other marvels about it, besides those above explained," &c. " Some say that when Ninus, king of (As-)Syria founded Nineveh, his wife, in order to surpass her husband, built Babylon in the plain with baked bricks, asphalt, and hewn stones three cubits broad and six long. Its perimeter was 355 stadia; the walls were forty cubits high and thirty broad, so that chariots could pass one another, and were flanked with gates with lofty towers. And she made brazen doors of a great height." According to Josephus, who quotes Berosus, Nebuchadnezzar built three walls round the interior, and three round the exterior of Babylon, or probably three round the new, and three round the old city. Within these walls were the celebrated hanging gardens. He built also high walks of stone, with all manner of trees upon them, to give the appearance of a mountain; besides which he made a paradise, which was called the hanging garden, to please his wife, who, coming from Media, loved a mountainous country. (Against Apion, book i.) 60) Chap. i. v. 1 — 4. 61) The walls of Nineveh were built, according to Eustathius, in eight years by 140,000 men. Those of Babylon in fifteen. (Berosus, Frag.) According to Quintus Curtius, a stadium was finished each day. (lib. v. c.26.) 62) Rich, however, mentions stones cemented with bitumen, as having been found in on excavation amongst the ruins opposite Mosul.

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD

⁕ =

⁕ =