The Synoptic Problem

Part 5 of 14

By J. F. Springer, New York

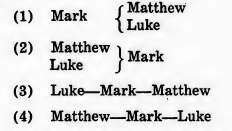

| 1. A Summarized Statement of Arguments for Markan Priority that are Based on Order. 2. The “Absorption” of Mark. The detailed investigation into the possibility of deriving, from the phenomena of order as they are disclosed in the first two Gospels, any substantial arguments favoring the dependence of Matthew upon Mark has been concluded. I claim that the evidence now available requires a negative answer. As the examination into this matter was necessarily long and more or less involved, the reader may welcome a condensed restatement. I proceed to make a brief presentation of the arguments for Matthaean dependence upon Mark that are based on order and of answers that may be made to them. The Argument From CorroborationThe argument from corroboration claims that Mark is the most primitive of the Synoptic Gospels, on the ground that its order is the only one of which it may be said that it is seldom or never without the corroboration of one or both of the others.1 Two Answers1. The argument is not based upon a correct statement of the facts. Mark presents a succession of 83 incidents. There are, accordingly, 82 sequences. Of these, 9 are without any corroboration; so that “seldom or never” does not correctly describe the situation. Eleven per cent (9 ÷ 82 = 0.11) of all sequences are without corroboration. 2. The argument is invalid, anyway. Even if it be allowed that all 82 sequences are corroborated, this would not avail to establish the priority of Mark over the other Synoptic Gospels, for the reason that the very assumption that Matthew and Luke are individually and separately dependent upon Mark operates to make their corroboration of little or no evidential value. If, indeed, the Gospel of Matthew followed the order of its exemplar Mark, then the Matthaean order is no effective witness to the correctness of the Markan succession of events. Similarly, the assumption that the Lukan order was obtained from the Markan affords no real testimony to the correctness of this Markan order. The Lukan order would become a reflection of, or at most an acquiescence in, the Markan progression of incidents. The Explanatory ArgumentIn accordance with the explanatory argument, Mark is claimed as the most primitive of the Synoptic Gospels, on the ground that its order may be set up as a standard, upon comparison with which each of the other orders may be explained as a derivative.2 This Argument A Crude FallacyIt is an elementary error in logical procedure to claim that an hypothesis is established when it has been found to afford a satisfactory explanation of the facts. There may be other competent causes besides the one which constitutes the hypothesis, and these may be severally and equally competent to provide an explanation. In order to complete the proof, it is necessary to exclude all but the one. In the present case, the hypothesis that Mark was exemplar for Matthew and Luke is but one of four equally probable explanations. The moderately close correspondence of the Markan order with that of each of the other Synoptic Gospels and the comparatively wide divergence between Matthew and Luke in respect to order may be regarded as the facts to be explained. If we assume Mark prior both to Matthew and Luke, we have one explanation. But there are three others. Here are all four:

In all four alternatives, Mark always stands next before or next after Matthew and Luke. The moderately close correspondence of the Markan order with both the other orders is thus explained. In all the alternatives, Matthew and Luke may be regarded as independent of each other, or else as deriving their dependence indirectly through a third document, Mark. The wide divergence in order between Matthew and Luke is thus explained. The Explanatory Argument Applied To DetailsThe explanatory argument, when applied in a large way, yields, as we have seen, four equally probable alternatives. Two of these make Mark a source for Matthew:

And two make Matthew a source for Mark.

If it be granted that these four alternatives exhaust the possibilities, the way is open to take a further step and effect a reduction in the number. Thus, if a decision can be reached as to the relative priority between Matthew and Mark, two alternatives may in consequence at once be eliminated. If the Markan order can be shown to be a source for the Matthaean, this result will carry with it the elimination of Nos. (2) and (4) and in this way narrow the possibilities to Nos. (1) and (3). Strenuous efforts have been made to set up the Markan order as the more primitive and to show the Matthaean might have been derived from it.3 Reference may be made particularly to writings of the following investigators: C. Lachmann (1835), H. J. Holtzmann (1889), W. C. Allen (1900), B. W. Bacon (1920). The procedure, if successful, would not establish that the order of Mark is more primitive than that of Matthew, but only that it is permissible so to regard it. In fact, we have the explanatory argument over again. This time, however, it deals with details. Actual cases of deviation are brought forth and discussed, particularly those cases which occur in the earlier part of the Ministry as set forth in the Synoptic Gospels. Two Answers1. None of these efforts has produced an explanation which is tenable in respect to its competence to explain the facts.4 2. The argument is inconclusive, anyway. Even if it be granted that a competent explanation of the Mat-thaean deviations from the order of Mark has been found, we are still confronted with the possibility of an alternative explanation equally competent to explain the facts. That such an alternative really exists is shown in Answer No. 1 to “The Indirect Argument.” The Indirect ArgumentA decision, from the point of view of order, could be obtained, it has been thought, as to the relative priority between Matthew and Mark, if it could be shown that it is impossible to derive the Markan order from the Matthaean. This argument is based on the view that we have but two alternatives, so that the exclusion of one necessarily results in the establishment of the other. In order to effect such an exclusion, the assertion has been made that no motive can be assigned to account for the Markan deviations, when Matthew is set up as exemplar.5 Two Answers1. A motive can be assigned. As both documents continually assert a chronological purpose on the part of the writer, it may be claimed that the Markan compiler had, when making his deviations, the motive of correcting the chronology.6 2. It is unnecessary to assign a motive. It may be maintained, though perhaps not conclusively proved, that when the autographs came, sheet by sheet, from the hands of the writers, there were no deviations of one order of events from the other order. That is to say, there is in the field a thoroughly tenable—and, in the present case, this means sufficient—explanation of the Markan deviations which does not require any motive to be ascribed to the writer of Mark. The deviations exist, because an accident occurred to each of two ancient MSS. of Mark, before or after the sheets were secured together in a roll or a codex, in consequence of which the order of portions of the document was lost and in the re-assembling was only imperfectly recovered.7 In view of the fact that the modern advocacy of Mat-thaean dependence, in so far as this advocacy is based on the phenomena of order, was initiated as far back as 1835 by the publication of Lachmann’s paper, it may be of service to the cause of truth to tabulate here, though perhaps not exhaustively, principal reasons why a constructive investigation covering nearly nine decades, proves, upon a scientific inquiry into the basis for its alleged results, pitifully unable to justify itself. I proceed to make such a tabulation, and venture to suggest to those who in the future may be minded to continue urging the derivative character of Matthew by arguments based on order that prior to their assumption of the risk they study well this table of failures. Reasons Why The Study Of Order Has Misled Investigators1. Failure to ascertain the facts of order. 2. Failure to recognize the evidences of chronological intent contained in Matthew and Mark. 3. Failure to develop the four alternatives which equally well explain the moderately close correspondence in order when Mark is compared separately with the two other Synoptic Gospels, and the considerable difference in order when Matthew and Luke are brought into comparison. 4. Failure to develop to what extent the Markan order may be viewed as having been derived from Matthew. The “Absorption” Of MarkModern investigation and discussion with respect to the Synoptic Problem have now been going on for about a century and a half. As the total of text involved is quite moderate, one would naturally expect that by this time a clear understanding of the facts and a thorough apprehension of the logical processes necessary to the development of their significance would have emerged. But this has not been the case. We have already found in our examination of the matter of the order of events that apparently all or nearly all writers on Synoptic matters have been ignorant of the exact facts relative to the correspondences with, and deviations from, the Markan order or events that are to be found in Matthew and Luke when sufficiently precise, and adequately controlled, comparisons are made. Nor have Synoptic investigators appeared to be well advised as to the futility of inferring anything as to priority from the “corroboration” of the Markan order. They have, moreover, seemed unable to apprehend that the possibility of explaining in a general way the orders of Matthew and Luke from the order of Mark confers no right to single out Mark as the earliest of the three documents. In short, in respect to the matter of the agreements and disagreements in order, Synoptic scholars can scarcely be adjudged as having acquitted themselves as scientific investigators. The most elementary requirements of a scientific procedure have been wanting. The facts have not been ascertained nor the possible modes of the logical utilization of the facts established. We now come to the consideration of the “absorption” of Mark by Matthew alone or by Matthew and Luke conjointly. Here, too, confusion reigns. Its grip upon the minds of investigators may perhaps be less absolute. At the same time, it appears to be just as effective in promoting error. Some investigators say that nearly the entire substance of Mark is to be found again in Matthew. Thus, we have B. Weiss and W. C. Allen making such statements as the following:

These statements leave much to be desired. Such expressions as “der game Inhalt” and “the entire substance” are quite objectionable, since they tend to convey the meaning that what reappears in Matthew, if we except a few passages, is equivalent to the detailed text of Mark. This is not the case. In Matthew are to be found, in some form or other, nearly all the incidents of Mark. If, disregarding the Infancy Section consisting of the first two chapters, we should draw up a table of contents for Matthew in the form of a list of the incidents and should do the same for Mark, then the Matthaean table of contents would be found to contain nearly all the items of the Markan table of contents. That is to say, nearly all the incidents of Mark, considered as whole incidents, are paralleled in Matthew. But incident for incident, the Markan accounts are, on the average, far richer in information. There is in fact a large percentage of the total of text in Mark that is unrepresented in Matthew. Roughly, it amounts to about 27 per cent of the entire document. If by “substance” we mean content of import, then it is absurd to say that Matthew contains nearly all the substance of Mark. However, some writers treat this matter in language not subject to the criticism that has just been set forth. Amongst these may be mentioned F. H. Woods9 and H. B. Swete.10 Consider in this connection the following excerpt:

Other writers confuse the matter of the “absorption” of Mark by conjoining Matthew and Luke and stating to what extent the Markan material is reproduced when no point is made as to whether it is paralleled in the one or the other Gospel, or whether it is paralleled in both. Apparently, they consider it unimportant to state just what is the extent of the Matthaean parallelism of Mark and just what that of the Lukan. In their eyes, the important thing seems to be the view that only a small part of the text of Mark is unrepresented in the aggregate of Synoptic material made by lumping Matthew and Luke. The confusion produced is due not so much, nor perhaps at all, to any substantial inaccuracy of exposition, but rather to the apparent impossibility of making their statement the logical basis of an inference as to the relative priority between Matthew and Mark. That is to say, the statement once made and allowed to be correct seems to have no significance in connection with the question as to which of the first two Gospels is the derivative and which the primary. Examples of this mode of presenting the “absorption” of Markan material follow. The reader is to remember that my criticism of these refers not to such forms of statement as those in which “almost the entire Markan material” is said, but “almost the entire Markan table of contents” is meant; but rather to that mode of presenting the conception of an “absorption” of the Markan material which requires Matthew and Luke to be conjoined in order to make it possible to say that almost “the entire material” of Mark is to be found again, yet does not distinguish in this matter the parts played by these two Gospels.

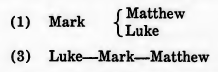

I do not call in question the truth of the foregoing statements. That is, for the time being at least, I am ready to allow that a statement is true which in effect asserts that the Markan content of import, within 30 or 50 verses, can be found again, not in Matthew, not in Luke, but in a conjoint document made up of Matthew and Luke; but what is to be done with such statements? They appear to have no importance as an argument for the priority of Mark. The fact that the entire substance of the document B can be found in the documents A and C, partly in A and partly in C and partly in both, does not lead to the conclusion that B was prior to A and C, nor to the conclusion that B was prior to A or C. The excerpts seem to me to have no especial importance of any kind, unless perhaps in connection with the old Griesbach hypothesis which made Mark an excerpt from Matthew and Luke. It might thoughtlessly be said, as in effect it is said by Rudolf Knopf, that there was no reason for the Markan writer to compile his book, if everything he was going to put into it was already available in Matthew and Luke. It is sufficient for the moment to say that it is the very business of compilers to set forth simply what is already extant in the world. In the present case, the Markan compiler would, indeed, be compiling almost exclusively from just two sources and this may seem a mild difficulty. But, when we consider that his purpose may very well have been the compilation of a short, highly authentic narrative which should set forth the mighty works of the Savior rather than His teaching, then we may readily understand (1) why he should omit many discourses and quite a number of miracles and other incidents, and (2) why he should limit himself pretty closely to two such authoritative documents as the First and Third Gospels. The reader will please not understand me to be an advocate of the Griesbach hypothesis. I am engaged, just now, in pointing out that the mere fact that, if we concede the Markan import as almost completely contained in the combined texts of Matthew and Luke, this concession appears to lead to little or no information respecting the question of priority between Matthew and Mark. There are at least four alternative explanations, the Griesbach hypothesis being one, and these four are, at the moment, equally probable: (1) Mark a source separately for Matthew and Luke; (2) Matthew and Luke conjointly a source for Mark; (3) Luke a source for Mark and Mark in turn a source for Matthew; and (4) Matthew a source for Mark and Mark in turn a source for Luke. In the excerpt from Holtzmann, the inference as to Markan priority is slovenly drawn. One would conclude that the writer thought the mere fact that the content of Mark was to be found again in the two other Gospels was sufficient to indicate its priority to them. In the context, he goes on to explain, not how one would be entitled to draw such an inference, but how the Markan order, not content, may be set up as the primitive one.14 In short, we are simply told that the occurrence of the Markan substance in Matthew and Luke conjointly is an indication of the priority of the Second Gospel. Of course, there is no basis in logic for this. In fact, the same writer elsewhere admits another alternative. Thus, we read in a volume devoted to The Synoptic Gospels:

Here we find two alternatives allowed—just two. One is the view that the Markan writer followed Matthew and Luke excerpting from both, and the other is the conception that he preceded both and provided them with a common exemplar. There are, however, two additional alternatives, both of which are also explanations of the fact that nearly the whole of the Markan substance may be traced in a combination of Matthew and Luke. These additional alternatives may briefly be expressed as lines of derivation in which the three Gospels succeed one another as follows: Lk—Mk—Mt Mt—Mk—Lk Those who propose to use the fact of the reappearance of the Markan substance in the combined text of Matthew and Luke as the basis of an argument favoring Markan priority, would do well to discipline themselves into an adequate realization of the exact logical situation. Their recognition of the limitations imposed by logic would be pretty sure to win the respect of competent persons. There are at least four independent alternatives. If these be set up and shown to exhaust the possibilities, then it becomes necessary to proceed by a process of elimination, and in this manner to establish the truth of their favorite by the reasoned exclusion of all the rest. There is a statement of the argument for the priority of Mark that is supposed to be derivable from the “absorption” of Markan material by Matthew and Luke which it is rather difficult to classify. From the facts as to choice of material, the author of the statement seeks to draw the inference that the Second Gospel preceded both the First and Third and was in fact their common exemplar. There is thus a union of Matthew and Luke in making them both followers of Mark. But in presenting the facts, they are separately dealt with, so that the “material” which Matthew is viewed as having taken over from Mark is distinguished from that which Luke is thought to have absorbed. The expression “material” (Stoff) is to be understood in a broad way. Thus, when Knopf says that Matthew contains, with a few exceptions, the material of Mark, we are to understand the sense to be that Matthew presents pretty much the same incidents and not that the First Gospel parallels the Second in the matter of details as well as in choice of topic. For example, Matthew contains an account of the incident of The great herd of swine equally with Mark, but the Matthaean narrative is much briefer and deals with a considerably less number of details, as may be seen by comparing Mt. 8:28–34 and Mk. 5:1–20.

When the author of the foregoing statement says, “almost the entire Markan material” in recounting what he supposes that Matthew absorbed and “nearly the whole of Mark” in stating what Luke is conceived as having taken over, we must understand that what is meant is “almost the entire” Markan range of incidents. If we understand the sense to be that Matthew and Luke separately absorbed nearly all the details contained in Mark, then the statements of the amounts transferred are absurdly untrue. In drawing his conclusions, the author couples Matthew and Luke and considers whether Mark preceded the pair or followed. First, he seeks to conclude against the view that Mark followed the two others, by claiming that under this assumption it would be impossible to explain the omission of so much excellent material when drawing from Matthew and also when drawing from Luke. Second, he goes on to conclude further against this view of a Mark posterior to the others by the claim that the assumption makes of the Markan writer an author without a purpose, one who had nothing new to add to his predecessors. One may well ask, But why consider the question of Markan priority or posteriority as if it were merely a question whether Mark preceded both Matthew and Luke or followed both Matthew and Luke? Why group the First and Third Gospels as if some indissoluble bond held them together? No doubt, it is the ghost of the old Griesbach hypothesis still on the trail of the Germans and those who take their guidance from them. This view arose prior to the Two Document Hypothesis and had to be combatted by the advocates of the latter. The Griesbach hypothesis made Matthew and Luke both predecessors of Mark, the last being conceived as a composite derivative of the others. V. H. Stanton supposes that Keim was the last eminent writer who advocated the Griesbach hypothesis. If this reflects the state of affairs, it would appear as if it were not thought impossible that the dead might at this late day still need to be killed again. However, we are but mildly interested in the psychology of the matter. There are other alternatives besides those set up by these rival hypotheses. To them may in fact be added two others—Lk-Mk-Mt and Mt-Mk-Lk. Consequently, with four alternatives instead of two on his hands, out author is attempting far from enough when he seeks merely to eliminate but one rival. Even if one were disposed to grant that Knopf had gotten rid of the Griesbach assumption as to the derivation of Mark from both Matthew and Luke, two other rivals remain. As to the view that Mark’s posteriority to Matthew or to Matthew and Luke is embarrassing because it requires us to assume that the Markan writer must then have passed over much notable material, I may point out as sufficient answer for the present that in the first place I have no desire to place Mark after Luke as well as Matthew. It is enough to make Mark a derivative of Matthew alone. In the second place, an excellent reason may then be assigned for Markan omissions of Matthaean topics. All that is necessary is to conceive that the writer wished to set forth principally the deeds of Jesus and was therefore quite willing to omit not only the Infancy Section but the Sermon on the Mount, the Discourse to the Twelve when about to set out on their missionary tour, the Discourse as to John the Baptist, four of the parables in the Matthaean cluster of seven, and other discourse material. There are but few incidents concerned with the activities of Jesus that are to be found in Matthew but not in Mark. A desire to produce an account mainly narrative, having to do only with the public life of the Savior, is a perfectly intelligible and reasonable purpose. A brief but sufficient answer may be given to the question raised by Knopf, in so far as the assumption of a prior Matthew is concerned: “Why did the Markan author write at all, if he was able to present absolutely nothing that was new, but only an abridged excerpt?” He did have something new to present. This concerned whole incidents and a mass of supplementary detail, which altogether amounted to about 27 per cent of the Markan text. The writer of Mark added but few topics, but he increased very much indeed the total of information. Mark is by no means a mere excerpt. This Gospel may, under the hypothesis of direct dependence between the First and Second, be viewed as reproducing the framework of the Matthaean narrative of the public life and much of the form, content and language. At the same time, much, very much, has been added to the content. This additional material appears, in large part, in the form of supplementary details. So, the Markan author had abundant reason to write. But the idea appears to have found lodgment also in England that if only the Griesbach view of the posteriority of Mark to Matthew and Luke could be destroyed, then the priority of the Second-Gospel to the others would be established. Logically, it is, of course, absurd to set up no more than the two alternatives. That is to say, it is absurd to maintain upon the premises given that either Mark is the root from which the others sprang, or else it is the stem and flower supported by them. We are not entitled to say, with respect to Matthew and Luke when regarded as a pair of documents, that Mark must be either cause or else effect. There may be a measure of explanation for this rather strange point of view in some feeling that all the other competing hypotheses had already been eliminated and that these two were the only possible survivors. However the matter may be explained, those who examine writings on Synoptic topics are pretty sure to run across what appear to be survivals of a conflict with the Griesbach hypothesis. I think perhaps there is a trace of such a survival in the second of the following excerpts, both from the same book. At all events, these excerpts constitute a good presentation of the view that Mark must have been prior to Matthew and Luke because of the way in which these two, considered together, reproduce the Markan table of contents. But let Professor Peake set this forth.

It may at once be agreed that we have, in the foregoing two excerpts from Professor Peake, a correct statement in so far as they assert the broad facts (1) that the Matthaean and Lukan narratives of the public ministry both begin with the same incident with which the Gospel of Mark begins and (2) that from this point on it is generally the case that whatever incident is included both by Matthew and Luke that same incident is also an event in Mark. However, when we come to the question of the difference in choice of incident as between Matthew and Luke, it is, I think, a very considerable error indeed to say that these two Gospels “agree in the main within the limits covered by the Gospel of Mark.” It will perhaps be sufficient to point out that a comparison of Matthew and Luke “within the limits covered by the Gospel of Mark” will disclose, amongst other differences, two quite extensive ones. (1) Matthew, in the section 14:23–16:12, presents a series of eight consecutive incidents, none of which is to be found in Luke. (2) Luke, similarly, has an equal or perhaps a larger number of non-Matthaean incidents in 9:51–18:14.17 It is not the fact then that large differences between Matthew and Luke, in respect to choice of events, are confined to the two Infancy Sections (Mt. 1:1–2:23 and Lk. 1:1–2:52) and to those portions which record the happenings which followed the incidents of the early morning of the day of the Savior’s Resurrection. The case, is however, more damaging than this. It is not possible to assert with any degree of confidence that the departure of Matthew and Luke, each from the other, occurred at the end of Mark. We do not know that Mk. 16:8 is the end point. Very probably, Mark was originally a longer document. It is not permissible, then, to insist that Matthew and Luke agreed all through from the appearance of John the Baptist to the point where the Second Gospel came to an end. If the endeavor is made to evade this conclusion by saying that when the First and Third Gospels were written the book of Mark ended exactly where it does now,—that is, at 16:8—I may point out that this assumes the thing which it is sought to prove —namely, that Mark ante-dated both the other Synoptic Gospels. The resultant situation may be stated as follows: 1. In the case of nearly all incidents common to Matthew and Luke, the same incident is also to be found in Mark. 2. The first of the incidents that are common thus to all three Synoptic Gospels is also the very first of the Markan narrative. That there is some significance to be attached to these facts is, perhaps, not to be denied. That they are, however, premises sufficient in their import to warrant the conclusion that Mark was a source for Matthew and Luke, I do deny. No doubt, if we assume the Second Gospel as a source for the others, we have an explanation of the two facts. This assumption may accordingly be regarded as a competent cause, at this stage of our inquiry. But, if we are going to deal with the matter upon a scientific basis, it will be necessary to determine whether other competent causes may not also be set up. As a matter of fact, two other explanations may be made of facts Nos. 1 and 2. That is, there are two assumptions which may be added to the first one already before us. They may briefly be expressed as follows: Lk—Mk—Mt Mt—Mk—Lk That is to say, in the former case, we assume that Mark was derived from Luke and that Matthew in turn was derived from Mark. In this way, the duplication of an incident in Luke and Matthew is provided for by the fact that Mark is in an intermediate position. The second assumption may be shown, in a similar manner, to afford an explanation for fact No. 1.18 As to fact No. 2, it seems sufficient to point out that it is reasonable to assume that the purpose for the composition of the Second Gospel was to provide a short and authentic account of the events (as distinguished from the teaching) of the public ministry. This would account for the omission of an Infancy Section, although such a section was in the exemplar. That the first incident of the ministry should be the appearance of John the Baptist is no cause for surprise, as may be perceived upon considering the fact that the first event narrated by the Fourth Gospel is also this same appearance. We have had before us in the preceding discussion certain broad facts as to the inclusion in Matthew and Luke separately of parallels to a very considerable proportion of Markan narratives; and also the conception that nearly the whole of the import of Mark is to be found again in the conjoined text of the other Synoptic Gospels. What is the significance of these things? So far, no final answer has been ascertained; but it has been pointed out that prominent advocates of Markan priority are in error in claiming a decision favorable to their view, since other alternative exist. It remains to inquire, in connection with the “absorption of Mark,” as to how the matter stands when a more detailed examination is made and when a proper consideration is given not to one alternative but to all.

|

|

|

|

|

1) See, for an extended discussion of this matter, BIBLIOTHECA SACRA, January, 1924, second installment of my investigation entitled “The Synoptic Problem,” pp. 59-77. 2) For a fuller treatment of this matter, the reader is referred to pp. 78-80 of the issue of BIBLIOTHECA SACRA, already cited. 3) See, for a considerable treatment of the matters here in question, the whole of the third installment of the investigation already referred to in note 1, and to the earlier part of the fourth installment. These are to be found in BIBLIOTHECA SACRA, April and July, 1924, pp. 201-239 and pp. 323-346. 4) These explanations fail in two principal respects: (1) either they are unconvincing because of the assumptions that must be made in order that they may be workable, or because there is a plain failure to meet the situation in sufficient detail; and (2) they are out of accord with an important part of the evidence. (1) With respect to the first point, it is pertinent to call attention to the fact that the Lachmann explanation requires three very considerable assumptions: (a) that there was in existence prior to the composition of Matthew a document or definite body of tradition consisting of the great Matthaean discourses and arranged in the present Matthaean order: (6) that this order did not fully reflect the order of delivery; and (c) that the compilers of Matthew preferred to follow the non-chronological order when inserting the narratives of events rather than the known historical succession of these narratives now preserved to us in the Second Gospel. The Holtzmann explanation is flagrantly inadequate because it does not grapple (when dealing with the Ten Miracles between the Sermon on the Mount and the discourse to the Twelve when they were about to go forth upon their missionary journey), with the details of the Matthaean deviations from the Markan order. The explanation of Allen demands that we conceive the Matthaean compiler as actuated by the desire to present three groups of three miracles each, the first to exemplify healings of disease, the second to present manifestations of power over natural forces, and the third to set forth displays of Christ’s power to restore life, sight and speech. This last group ignores the healing of the woman with the issue of blood and is a cluster with no comprehensive motive to give it coherence. It is not even an arrangement in the form of a climax, as Bacon points out. Bacon’s explanation proposes Ten Mighty Works in Matthew, chapters 8 and 9, and divides this series into two groups of three and one group of four. The motives proposed for the several groups are (1) testimony to Israel, (2) increase of faith, and (3) parting of belief from unbelief. That these were actual motives in the mind of the writer is opposed by the fact that in each group occurs one or more miracles which are not at all outstanding examples of the corresponding motive. The curing of Peter’s mother-in-law and the miracles not particularly described, and occurring upon the evening of the same day, are not outstanding examples of “testimony to Israel.” The miracle performed when the demons were permitted to enter the great herd of swine is not an outstanding example of “increase of faith.” Nor may the miracles concerned with the woman having the issue of blood and with the two blind men be set up as noteworthy examples of the “parting of belief from unbelief.” In short, the efforts of all four writers to provide an explanation for a part or the whole of the more serious of the Matthaean deviations from the Markan order are decidedly unconvincing when considered from the point of view of explanations. (2) With respect to the second point that the explanations are out of accord with an important part of the evidence, I may say at once that all these explanations disregard the numerous assertions of chronological intent scattered throughout both Matthew and Mark, about 100 instances occurring in Matthew and about 40 in Mark. [It will perhaps be not especially irrelevant at this point to call attention to the fact that we are by no means compelled to regard the writer of either Gospel as a historian wrongly informed as to the chronology when we view both as intent upon carrying out the chronological purpose evidenced so frequently in their Gospels. The Markan deviations from the Matthaean order may be explained otherwise than by referring them to the writer of Mark. See the article by the present writer in the April and July (1922) issues of BIBLIOTHECA SACRA, entitled The Order of Events in Matthew and Mark, pp. 131-152 and 321–350.] 5) The “Indirect Argument” is treated with greater fullness in the latter part of the fourth installment of the investigation before mentioned, that is in BIBLIOTHECA SACRA, July, 1924, pp. 346-354. 6) It should be particularly noted that this hypothesis of a Markan compiler intent upon correcting the chronology of his exemplar does not need to have any greater support than the hypothesis that a Matthaean compiler had the Markan order before him. The four explanations are all enormously weakened by the fact that they do not take into account the great basic fact that both Gospels repeatedly assert chronological intention. It seems folly to conduct searches for motives, when both Gospels are everywhere calling attention to chronological purpose. Nor can the hypothesis be very well maintained of a Matthaean compiler controlled by a purpose to set straight the chronology of Mark, since it is almost necessary to add to this purpose another which had as its object the construction of a series of Ten Great Works between two considerable discourses. That is to say, the view that a Matthaean compiler corrected the chronology of Mark is complicated by the fact that Ten Great Works do stand between the Sermon on the Mount and the Address to the Twelve. An original writer could very well carry out the combination of purposes, but not a compiler. 7) An extended presentation of this explanation has already been cited at the end of foot-note 4. 8) So ist also mit Ausnahme einiger ganz kleinen Stücke, deren Uebergehung sich uns aufs Einfachste erklärt hat, der ganze Inhalt des Marcus in unser Evang. übergegangen und zwar in derselben Anordnung und Gruppirung. . . . 9) Studia Biblica, Vol. II (1890), article “The Origin and Mutual Relation of the Synoptic Gospels” (November 16, 1886), pp. 61 f., sections Nos. 1 and 2. 10) The Gospel according to St. Mark (1902), Introduction, p. lxix. 11) Bei Mt. liegt die Sache so, dass er fast den ganzen Mk.-Stoff, mit Ausnahme von acht kurzen Perikopen, zwischen 3:1 und 28:8 bringt. 12) Dagegen liegen ungleich mehr Anzeichen der Ursprünglichkeit auf Seite des 2. Evglms. Bis auf etwa 30 im Zusammenhang des Ganzen verlorene Verse ist der gesammte Stoff desselben in den beiden anderen Werken wiederzufinden. 13) Dafür sprechen in der Tat die stärksten Gründe. Ich deute einige an. Hätte Marcus die andern Evangelien benutzt, so könnte man nicht verstehen, weshalb er so vieles von ihrem Stoffe aus-gelassen hätte; wenn Markus dagegen die Grundlage ist, so haben die beiden Nachfolger fast sein ganzes Evangelium in sich auf-genommen; weshalb sie aber einige wenige Stücke ausgelassen haben, das lässt sich durchweg gut erklären. 14) This succeeding context is given at length in the issue of BIBLIOTHECA SACRA for January, 1924, under the sub-heading The Explanatory Argument, pp. 78-88. 15) Bis auf etwa 30, im Zusammenhang des Ganzen verlorene, Verse, ist der gesammte Stoff des 2. Evglms. in den beiden anderen Werken wiederzufinden. Dies weist entweder auf ein Excerpt (Griesbach’sche Combinationshypothese) oder auf die gemeinsame Vorlage (Mc.-Hypothese). 16) I. Mk. ist die eine Quelle für Mt. und Lk.—Dieser Satz lässt sich mehrfach und eindringlich beweisen. 1. aus der Stoffauswahl. Der Erzählungsstoff des Mk. kehrt bei den beiden andern wieder. Bei Mt. liegt die Sache so, dass er fast den ganzen Mk.-Stoff, mit Ausnahme von acht kurzen Perikopen, zwischen 3:1 und 28:8 bringt. Unterbrochen wird der Mk.-Stoff bei ihm vor allem durch die grossen Redestücke (5–7, 10 u. a. w.), in denen er meist den ihm und Lk. gemeinsamen Stoff bringt, an dem Mk. keinen Anteil hat (vgl. unten). Lk. legt diesen ihm und Mt. gemeinsamen Stoff in seinen beiden “Einschaltungen” vor, dem Reisebericht, 9:51–18:14, und der “kleinen Einschaltung,” 6:20–8:3. In den Teilen nun, die ausserhalb der Einschaltungen liegen, kehrt bei Lk. nahezu der ganze Mk. wieder, mit Ausnahme von etwa zwölf zusammenhangenden Mk.-Stücken, unter denen manche sehr geringfügig sind, Einzelverse und angeben, unter denen aber freilich auch ein sehr umfangreiches steht: Mk. 6:45–8:26, die “grosse Lücke” des Lk., eine Perikopenreihe, aus der kein einziges Stück sich bei Lk. wiederfindet. Nimmt man an, Mk. sei nicht die Vorlage der beiden andern gewesen, sondern er benutze seinerseits den Mt. oder den Mt. und Lk., dann kann man nicht erklären, wie so er um die schönen und wertvollen Stoffe, die er bei Mt. in den trefflichen Kompositionen der Bergpredight, der Aussendungsrede, des Parabelkapitels, der grossen antipharisäischen Streitreden, u. s. w., bei Lk. in den beiden Einschaltungen las, sorgfältig herumging und sie weg lies. Warum schrieb Mk. überhaupt, wenn er gar nichts Neues, sondern nur einen verkürzten Auszug beiten konnte? So folgt schon aus der Auswahl des Stoffes, dass Mk. das älteste Evangelium und die Vorlage der beiden andern ist. 17) I cite: Lk. 9:51–56; 10:1–24, 25–37, 38–42; 13:10–17, 22–30, 31–35; 14:1–24; 17:11–19. 18) I do not enumerate the Griesbach Hypothesis as an alternative explanation, for the reason that it seems very improbable that with Matthew and Luke before him the compiler of Mark would include in his account almost all the incidents narrated in common by his two exemplars. There is thus a failure to explain fact No. 1. |

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD