The Synoptic Problem

Part 10 of 14

By J. F. Springer, New York

Small Matthaean Omissions Of Markan AdditionsWe have now had before us a succession of lists of short Markan passages involving matters of possible difficulty. One class of notices has not been included. That is to say, I am reserving for future consideration those short Matthaean omissions, or Markan additions, which are conceivably disparagements of the apostles. I am inclined to believe not only that the succession of lists of passages involving possible difficulty, which has already been presented, constitutes the most complete single statement of the kind in the literature of the Synoptic Problem, but that this statement is more comprehensive than any that could be made by combining all the tabulations of those who have maintained the priority of Mark over Matthew. Included in my lists are nearly all those instances which have been tabulated by W. C. Allen in his A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel according to St. Matthew (1907), Introduction, pp. xxxi-xxxiii, sec. 6 [see also his The Gospel according to Saint Mark (1915), pp. 23-24]; and by Sir J. C. Hawkins in his Horae Synopticae (2d ed., 1909), pp. 117-125. I have added many others. It would appear that the reader is admirably situated to weigh the matter of priority in the presence of the kinds of evidence that have been presented in the foregoing lists. If such evidence really has any substantial value in determining whether Matthew or Mark is the derivative document, then the reader has had before him what may perhaps be regarded as fairly equivalent to the possible total. In fact, if evidence of this description affords a basis upon which may be erected an argument for the compilation of the First Gospel from the Second or an argument against the derivation of Mark from Matthew, then one or both of these arguments should be disclosed upon a due consideration of the evidential aggregate now available to the reader. If the secondary character of Matthew, and the non-secondary character of Mark, do not receive substantial support from this collection of notices, there is little hope that the future will enlarge it to such an extent that it will then afford an adequate basis for these contentions. Omissions or AdditionsAre these short notices, found in Mark but not in Matthew, omissions or additions? That is, did a Matthaean compiler omit them from his compilation, or did a Markan secondary writer add them to the information obtained from his exemplar? If they are omissions, then the book of Matthew is a compilation based on the Gospel of Mark. But, if they are additions, then the First Gospel preceded the Second in time and supplied it with its framework and something more than two-thirds of its substance. However, although I maintain the position that if one or the other of the two Gospels is a derivative of the remaining one, Mark is the derivative and Matthew the primary—although I hold this, I am nevertheless not much concerned to show that the preceding aggregate of short notices must be viewed as consisting of additions. I am content to make it clear that they may be so considered. “Must” is unnecessary to my programme; “may” is quite sufficient. I am not depending upon these notices to prove my case. On the other hand, passages of this character constitute the basis for part of the argument relied upon by certain investigators to establish the proposition that Matthew was compiled from Mark. We are entitled to expect, then, from those who see in these Markan fragments involving possible difficulty a considerable logical reason why Matthew is to be viewed as the secondary document, an inquiry conducted along scientific lines and directed (1) to the uncovering of all important relevant evidence, and (2) to the exposition of the logical principles involved in the utilization of this evidence. I am aware of no such inquiry, and have no substantial reason to believe that it anywhere exists. Investigators of the Synoptic Problem, when conducting inquiries into the various classes of facts, have, it would appear, not been particularly interested in developing all the evidence. Part of the evidence seems to have satisfied them. Nor is it apparent that they have busied themselves successfully in opening up the logic necessary to the scientific interpretation of the data. This is my impression of the general situation. Abundant illustration of the correctness of my view may be found in preceding instalments of this present examination of the bases, upon which rests the proposition that in Mark we have a parent document and in Matthew a daughter writing. It is the business of those who would advance the short Markan notices as evidence of the secondary character of Matthew to show that they do in fact constitute a logical basis for the inference they wish to draw. I might leave the matter with this remark and await the presentation on their part of a development of the whole of the evidence, and of the logical principles controlling the situation; but I am persuaded that if ever an adequate inquiry would be made it would be long before it would be undertaken and carried to its conclusion. Apparently, scientific procedure and advocacy of Markan priority do not go hand in hand. So, then, let us investigate for ourselves, even though it is not our business to do so. Let us take as one point of departure the claim that the presence in Mark of a lot of short passages involving possibility of difficulty. and the absence of these passages from the Matthaean text constitute evidence of a substantial character that the difficulties were omitted by a compiler engaged in constructing the First Gospel. What logical basis for this claim can be discerned? It may at once be said that the logical situation is simplified by the consideration that ex-hypothesi we have but two possibilities. Either Mark is the primary document and Matthew the secondary, or else Matthew is the exemplar and Mark the compilation. The fact that these two propositions exhaust the possibilities enables us to find in the denial of the one an assertion of the other. Apparently, no direct argument for the secondary character of Matthew can be based on the aggregate of short notices. For example, it does not seem possible to infer directly, from the presence in Mark of the phrase, “with anger,” and from its absence from Matthew, that we have to do with an omission. There is nothing in the Matthaean text, it would seem, to indicate that something has been left out, that the writer was aware of an additional piece of information but decided to omit it. We may see, perhaps, that the language in Matthew is such that it may very well have been founded on an account containing the phrase in question. But, even so, we get no affirmative argument. The utmost we obtain is that there is nothing against the hypothesis of an omission made by the Matthaean writer. Nor is it apparent how to take a considerable aggregate of such instances and construct a direct argument that the passages are omissions—that the writer of the First Gospel was aware of them but concluded to leave them out. On the other hand, it is possible to proceed in an indirect manner. If it can be shown that the alternative proposition is untrue—that, in fact, Mark cannot be viewed as a derivative from Matthew—then this denial amounts to an affirmation of the proposition that Matthew is a secondary document based on Mark. We would then get by indirection what we are unable to obtain by a direct method. Here, then, appears to be the hope of the advocates of a derivative Matthew. If they can show that a Markan compiler, working with Matthew before him, would not have added the short notices, then the Second Gospel cannot be considered a compilation based on the First. The only possibility that would then remain is the one stated by the proposition that the Second Gospel was employed by the writer of the First. I proceed to set forth two logical methods in accordance with which the derivative character of Mark may be attacked. If it can be shown that all short passages present in Mark but absent from Matthew are members of a class characterized by difficulty, whether real or imaginary, then the fact of this limitation of the whole body of short non-Matthaean Markan notices to a single classification may be set up as evidence that these fragments are not additions but omissions. It is conceivable that an entire numerous group of short passages may be omitted by a compiler because all members of it involve difficulty; but it is hardly possible that a secondary writer would add a considerable number of brief notices, every one of which is characterized by the circumstance that it contains elements of difficulty. A large number of difficulties may be the only omissions, but they cannot be the only additions. This method of attack is effective, when applicable. In the present case it cannot be used, as the brief non-Matthaean Markan passages are by no means confined to the class characterized by the possession of elements of difficulty. There are, in fact, hundreds of short notices present in Mark but absent from Matthew in which no difficulty is discernible. (2) The secondary character of Mark may be assailed by introducing the element of time. We have already seen that nothing as to priority of composition is to be read out of the circumstance that one Gospel writer contains short passages absent from the work of another. Lists of such notices may be drawn up for any pair of the three Synoptic Gospels. That is, there is evidence, if the principle that absence of short passages signifies derivation be true, that each of the three documents was subsequent to each of the two remaining. We turn, then, to the matter of time. What hope remains to the advocate of Markan priority over Matthew, when the time factor is introduced? Our inquiry, accordingly, now centers upon the question, Would it have been impossible for a compiler, who was making his compilation at a somewhat later date than that at which the composition of Matthew took place, to make additions of the kinds indicated in the foregoing lists? That there is nothing impossible associated with the mere inclusion of such notices is evident from the very fact that they occur in the Gospel of Mark. Let us now introduce the time element and ask, Are we to suppose that the writer of this document could have included these difficult passages in his text upon the assumption that he was an original author but that he could, or would, not have done so upon the double assumption that he was a compiler and that he wrote at a somewhat later date than the Matthaean writer? It has already been pointed out that we are not at liberty to suppose that any impossibility attaches to the simple proposition that one early Gospel writer made minor additions when compiling from a document written by another. There remains, accordingly, only the time question. Did a change of Christian sentiment occur, during the period in which the four Gospels were written, which was of such a character as to deter writers from including in their works passages of the kinds illustrated by the Markan notices? If such a change of sentiment did opportunely occur, and if its existence and influence can be established, then we have, in the evidence for this existence and influence, some basis for claiming that a compiler could not have added what we find in Mark. This denial, as has already been sufficiently pointed out, would amount to an affirmation of the secondary character of the First Gospel. Unfortunately for the advocates of a derivative Matthew, however, it is apparently the case that not only can no substantial evidence for the early change in Christian sentiment and its influence upon writers be adduced but actual proof of the non-existence of this change can be set forth. In fact, all four Gospels are full of short passages involving the elements of difficulty. The entire period of Gospel composition is characterized by a disregard of the possibilities attaching to the inclusion of difficult matter. There are a few passages in Luke which may, perhaps, owe their form of language to the purpose of avoiding difficulty, and a lesser number in John which expressly avow such an intention.1 On the other hand, there are many instances in all four Gospels which afford, in their several aggregates, evidence of a cogent character that the writers made little or no attempt to exclude facts and forms of expression of a character suggestive of difficulty. The documents which they produced are too full of short notices, belonging both to narrative and to discourse, and involving difficult matters, for us to concede that at some point within the period during which the Gospel writings were produced occurred a change in Christian sentiment, such that from that time on great care was exercised to omit fragments of descriptive matter and of discourse material which, though true and authentic, were liable to cause trouble. I give tabulations which show—even though, perhaps, they fall short of completeness—the evidence as to the inclusion of fragments of difficult matter in Matthew, Luke and John. We are already familiar with the fact that in Mark there are numerous items of this character. It is to be noted that in the Matthaean list are enumerated passages of two descriptions—(1) those which, on the hypothesis of a secondary Matthew, represent additions made by the compiler upon his own initiative; and (2) those which are substantially repetitions of things found in his exemplar. The members of the former class are listed without any distinctive mark, and those of the latter class are indicated by the presence of an asterisk. As to the passages so distinguished, let it be observed that in them we have good evidence for the non-existence, at the time when the First Gospel was written—whenever that was—of any attitude upon the part of Christians of such character as to result, after its origin, in the elimination of troublesome passages. The Matthaean compiler was content to reproduce them from the Markan text lying before him. So, then, all the passages in the list, those marked and unmarked, constitute a heavy body of evidence in denial of the existence of a prohibitive attitude at whatever period the Gospel of Matthew was written.

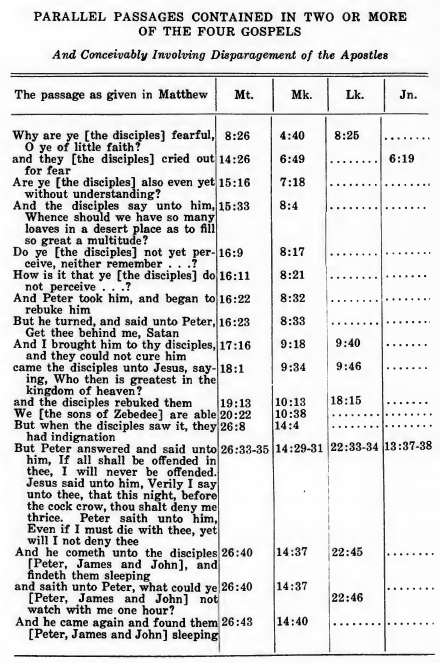

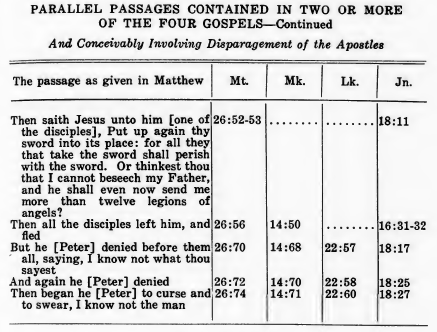

If now we make up a general list, including in it all the Markan, Matthaean, Lukan and Johannine passages which suggest difficulty and which occur in but a single Gospel, we will have a very weighty aggregation of evidence against the view that, at any time during the period when the Four Gospels were composed, a sentiment existed among the Christian communities of such character as successfuly to prohibit the inclusion of difficult matters. There may be here and there instances where the writer modified or omitted something that seemed provocative of possible difficulty. On the other hand, all the Gospels include, upon the initiative of the several writers, considerable amounts of such matter. And, when we arrange the Synoptic Gospels in accordance with any hypothesis of interdependence, we may readily gather together, in corroboration of the foregoing body of evidence, another mass of evidential material. This mass will consist of passages where secondary writers—and consequently writers later than the primitive one—have been content to follow their exemplars in giving publicity to sayings and narrative passages involving possible difficulty. As the Gospel of John is to be included as a source of evidence against a prohibitive sentiment, the great aggregate of passages showing a willingness or readiness to take the initiative or to follow an exemplar covers the entire period of Gospel composition. Disparagements of the Apostles.Certain writers2 have brought forth Markan passages which are perhaps susceptible of being viewed as tending to disparage the apostles. Such passages, it is thought by some, are indications of an early period. Quite a number are present in Mark and absent at the corresponding points in Matthew, and much the same conception has been entertained of them as of the unparalleled Markan passages conceivably involving difficulty of various descriptions. That is, they are, in the eyes of some, evidence of Markan priority and Matthaean dependence. However, when the whole field is comprised in our view —Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, all being taken into account—the result, as before is seen to be as follows: — (1) disparagement passages occur in every Gospel that has no parallels; (2) other similar passages occur, which, upon any hypothesis of interdependence of the Synoptic Gospels, are instances of disparaging matter accepted by writers later than the one or ones made the most primitive; and (3) still others occur in John alone. In fact, the Fourth Gospel also agrees with groups of one, two and three Synoptic writings in recounting disparagement matter. Disparagement passages were penned, of their own initiative, by all four Gospel writers, and other similar passages were retained by compilers amongst them. There is discernible no point of time in the whole period of Gospel composition after which, under any hypothesis of the order of publication of the several documents, it is permissible to assume that there existed a sentiment prohibitive of the inclusion of matter disparaging to the apostles.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1) Examples of what may perhaps be Lukan avoidances are the following instances of Markan expressions absent from Luke: Mk. 1:43, “And he strictly [or, sternly] charged him”; 1:45, “insomuch that Jesus could no more openly enter into a city”; 2:17, “when Jesus heard it”; 2:26, “when Abiathar was high priest”; 2:27, “The sabbath was made for man, and not man for the sabbath”; 3:5, “with anger”; 10:14, “when Jesus saw it” Express statements of John in avoidance of difficulty are these: Jn. 6:6, “And this he said to prove him: for he himself knew what he would do”; 7:22, “(not that it [circumcision] is of Moses, but of the fathers.”]) 2) 2 See, for example, W. C. Allen, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel according to St. Matthew (1907), Introduction, pp. XXXIII-XXXIV, sec. 7; and the same writer’s The Gospel according to Saint Mark (1915), pp. 20-23. Also, see J. C. Hawkins, Horae Synopticae (2d ed., 1909), pp. 121-122. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD