| Muršili II King of the Hittites 1339-1306 BC | |

|

He was the Son of Šuppiluliuma I

(Contemporary with Aššur-uballiṭ I of Assyria (See Peter Machinist (1987))

So spoke the enemies of the new Great King. Muršili succeeded to the throne at a young age due to his brother Arnuwanda’s unexpected and undesired death. Always ready to take advantage of such a predicament, the Hittites’ conquered territories dutifully revolted. But Muršili was a much more pious man than his father, a trait which would become characteristic of all succeeding Hittite Great Kings, and he chose to begin his reign tending to his religious duties. His father had spent so much of his time setting up garrisons in Mitanni that he had neglected the festivals of the Sun Goddess of Arinna. The punishment for this was the plague that took his life, that of his son, and even yet continued to haunt Hatti. Muršili felt that he would need the help of the Sun Goddess in order to be successful.

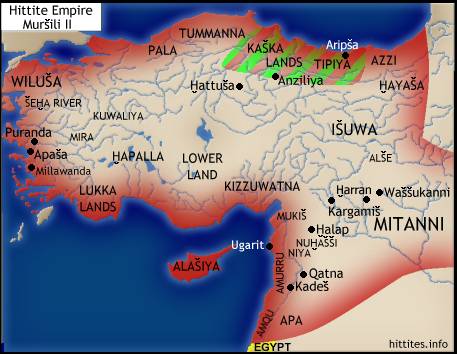

But he could not smite all the enemy lands at once, and so he made arrangements for his military officers to protect the status-quo. The Assyrians under Aššur-uballiṭ were still a hostile factor on the Hittite’s eastern flank, and so Muršili sent Nuwanza, the Great Wine Man, along with troops and chariots, to the aid of his brother Šarri-Kušuh (a.k.a. Piyaššili), King of Kargamiš. Both men were explicitly instructed to retaliate against any Assyrian attack. And yet the Assyrian threat appears to have been as empty at the beginning of Muršili’s reign as it had been at the end of Šuppiluliuma’s. Having heard that Hittite imperial troops had come to Kargamiš, the Assyrian ruler chose not to attack. Further, while these troops protected the eastern frontier, other troops guarded against the Arzawan enemy towards the western frontier (Extended Annals of Muršili II, Year 2). Also in the west, Muršili tried to maintain the status quo by recognizing Manapa-Tarhunta, whom he and his brother had helped earlier, in his position as ruler of the Šeha River Land. “The Sun Goddess of Arinna heard my words” Having duly attended to the proper religious festivals and the immediate security of his further borders, the following year Muršili began a long and distinguished series of campaigns which would affirm the Hittites’ newly regained position as a great power in the Near East. His attentions were first drawn to the Kaškans in the north, a region which would continue to trouble him for most of his reign. (YEAR 1) In this first campaign, the Kaškans located near the city of Turmitta rose up and began to attack that city. Muršili responded by attacking, looting, and burning down the two major Kaškan cities in the area, Halila and Dudduška. When the other Kaškans heard this, “all of Kaška” came to their comrades’ aid. It was of no avail. With the Sun Goddess of Arinna, the Storm God, and Mezzulla “running before him”, Muršili defeated his enemies and resubjugated the Kaškans near Turmitta. Having achieved this, he returned to Hattuša. But there was more trouble in Kaška. The Kaškans near the city of Išhupitta stopped sending Muršili the troop contingents that they were obligated to, and so Muršili marched forth and re-subjugated them as well, burning down one of their cities in the process. This reconquest didn’t last very long beyond Muršili’s stay in Išhupitta. (YEAR 2) With his brother Šarri-Kušuh protecting Kargamiš against the Assyrians, and having further sent troops into the Lower Land to protect against the Arzawans, Muršili was free to turn his small army to another northern campaign. This time he marched to the Upper Land and attacked the land of Tipiya, because it had stopped providing the troop contingents that it owed to the Hittite Great King. Its most important city seems to have been Kathaidwa, which Muršili attacked and burned down. He returned to Hattuša with his civilian captives and booty only to learn that there was trouble in Išhupitta again. So he turned around and subdued Išhupitta once more. But the leaders of the rebellion, Mr. Pazzanna and Mr. Nunnuta, former subjects of Muršili, escaped. Muršili marched after them. His first stop was at the city of Palhwišša. At this city, Muršili was helped by the fact that his foes had to depend upon levied troops, which were no match for Muršili’s regular army. The Kaškan army broke and fled before the Great King. So Muršili was able to burn down and plunder the city. He then moved on to the city of Ištahara, where he encamped. From here he was able to send back some plundered grain to Hattuša. Meanwhile the rebel leaders seem to have holed up in the city of Kammamma, so Muršili wrote to that city demanding their extradition. He then seems to have threatened the men of Kammamma with total destruction - a threat that proved effective. The men of Kammamma seized the two rebels, killed them, and subjugated themselves to Muršili. This seems to have quited Kaška for the time being, and Muršili returned to the city of Ankuwa where he passed the winter months. (YEAR 3) At the beginning of the third year Šarri-Kušuh seems to have been involved in some sort of altercation with troops from the city Huwaršanašša and one other city whose name is lost. The fact that these men fled into Arzawa indicates that Šarri-Kušuh’s troops who had been stationed in the Lower Land had been attacked. Muršili’s response led to what should probably be considered the most momentous achievement of his reign - the conquest and dismemberment of the kingdom of Arzawa. When Muršili’s enemies fled into Arzawa, Muršili sent messengers to its king, Uhha-ziti, demanding their extradition. Uhha-ziti refused. After all, he had no real reason to comply. The situation in the west seemed to have turned to the Arzawan’s advantage. He had allied himself with the King of Ahhiyawa, and as a result the King of Millawanda went over to the King of Ahhiyawa. Other leaders in the west were not slow to reassess their own positions. Manapa-Tarhunta, the King of the Šeha River Land, went over to Uhha-ziti. The land Hapalla and half of Mira-and-Kuwaliya (Mašhwiluwa retained control of the other half) were also allied with the Arzawan ruler. Wiluša, whose relations with Hatti always seem to have remained friendly even when forced out of treaty relations by the presence of Arzawa, was also allied with Arzawa at this time. With the entire western region of Anatolia under his control, it's no wonder that Uhha-ziti did not overly concern himself with the threatening demands of a distant and childlike enemy. It was a serious miscalculation. But Muršili’s immediate attentions were still pulled to the north, so that instead of personally dealing with the situation in the west he sent out two men, Gulla and Malla-ziti, to attack the rebel king of Millawanda. They succeeded and returned to Hattuša with their plunder and civilian captives. Uhha-ziti’s immediate response was directed towards that portion of the land of Mira which remained under the control of Mašhwiluwa, Muršili’s brother-in-law. Uhha-ziti attacked the city of Impaya. Mašhwiluwa was able to repulse the attack, but not utterly defeat the Arzawan king, who moved on and attacked the city of Hapanuwa. So the situation stood in the west as Muršili occupied himself in the north once again with the Kaškans in the vicinity of the city Išhupitta. The Kaškan city Pišhuru was beginning its rise to prominence, and it revived the city Palhwišša, which Muršili had burned down only the year before. Muršili was forced to march against this threat and burn down the city again. But this was not enough to pacify the territory. Kaškan troops occupied the city Kuzaštarina, and Muršili was forced to attack the city and conquer it. After this victory, Muršili pushed on as far as the city of Anziliya, reconquering the surrounding territories. The Conquest of Arzawa Having achieved a victory in the north, Muršili now turned his attentions to his problems in the west. It was time to deal with Uhha-ziti;

Muršili gathered his troops and began his march toward Arzawa. When he reached Mt. Lawaša near the Šehiriya River, he received what must be viewed as one of the most fortunate omens in history,

Having received such a favorable omen, Muršili continued his westward march. When he reached the city of Šallapa his brother Šarri-Kušuh joined forces with him, and then together they continued on. When Muršili reached the city of Aura, Mašhwiluwa drove into his presence and informed his lord about the effects of the thunderbolt on Uhha-ziti. The news could only have been seen as encouraging. Now was the perfect time to confront the Arzawan forces. Having been made lame by this object - possibly a meteorite which might still have been worshipped in Ephesus in the 1st century A.D. during the life of the Apostle Paul - Uhha-ziti could not come out against Muršili for battle himself. So instead he sent forth his son Piyama-Kurunta in his place. The forces met at the Aštarpa River near the city of Walma. The battle, once engaged, turned into a rout. Muršili pursued his fleeing enemies as far as Apaša itself. Uhha-ziti did not remain to defend his capital. He boarded a ship and sailed across the sea, never to return to the site of his ultimate humiliation. Piyama-Kurunta, his son, seems to have also fled across the sea to the King of Ahhiyawa (It is not known if Uhha-ziti and his son fled to the same place, or even at the same time). Now in control of the city, Muršili, a Hittite king with a central Anatolian capital, victoriously entered Apaša, a city with a port on the Aegean sea. The capture of the capital city did not immediately result in the subjugation of the entire land. Arzawans fled in two large bodies to Mt. Arinnanda and to the city of Puranda. Others had joined Uhha-ziti in his flight across the sea. Depending upon the assistance of his brother Šarri-Kušuh once again, Muršili chose to attack these places even though the year was growing short. He chose Mt. Arinnanda as his first target. It was a difficult goal. It lay on an island which was very high, overgrown, and rocky. It was impossible to attack it using chariots, and so Muršili used his infantry to climb up the mountain and lay seige to the fugitives. When the Arzawans began to suffer from hunger and thirst, they gave up and prostrated themselves at Muršili’s feet. As a result of this victory, Muršili claims to have personally gained 15,500 civilian captives, while his troops’ gains were beyond measure. After returning from Mt. Arinnanda, Muršili lay seige to the city of Puranda, the other hold out of the fugitive Arzawans. After having laid seige to the city, he gave them a chance to turn themselves in,

They refused to yield to him. Unfortunately for the Hittites, the season was definitely over. It had already begun to snow, and so Muršili drew back to the Aštarpa River and passed the winter at a fortress there. While there he celebrated the Month Festival. (YEAR 4) Over the course of the winter Uhha-ziti succumbed to his illness and died while still in exile from his land. When Spring came, one of his sons remained “in the sea” while the other one, Mr. Tapalazunawali, crossed over to the mainland and entered Puranda. Muršili broke winter quarters and marched back against Puranda. Tapalazunawali chose to come out for battle against his Hittite foe. His attack was repulsed, and Muršili laid seige to Puranda once again, this time cutting off its water supply. Tapalazunawali then snuck out of the city and fled, taking his children and some of his people with him. Muršili was informed of this and he sent troops in pursuit of him. Tapalazunawali himself managed to escape, but the Hittites captured his children and his people. With their leader gone and their water cut off, the city was doomed. Muršili captured the city and claimed to deport a further 15,500 civilian captives, while his troops took an even greater share. After this, Tapalazunawali seems to have fled to the King of Ahhiyawa “across the sea”, which is perhaps where he had come from before. But the situation, which seemed so favorable to the Arzawans the year before, had been dramatically reversed. So when Muršili sent a messenger by boat to the King of Ahhiyawa demanding Tapalazunawali’s extradition, he complied. Tapalazunawali and the civilians who were with him were all sent to the Hittite ruler, and were subsequently deported to Hatti. It was not only the end of the war, but also the end of Arzawa itself. In two campaign seasons, the youthful king had destroyed the only rival to Hittite power in Anatolia. The Organization of the West Having conquered Arzawa, it was now time for Muršili to organize it to suit Hittite policy. To this end, Muršili chose to break up the kingdom into several independent lands and send out Hittite troops to occupy and defend the new vassal kingdoms. But first Muršili had to be certain of his victory. Manapa-Tarhunta, the ruler of Šeha River Land, had betrayed him, and it was time for revenge. Muršili and his army set out for the Šeha River Land. When Manapa-Tarhunta heard that Muršili was coming, he grew fearful and wrote to the Great King,

But Muršili was not interested, replying,

Desperate times called for desperate measures, and Manapa-Tarhunta still had a trick up his sleeve. He sent out his mother, old men, and old women to Muršili to beg him to accept him as his vassal. When Manapa-Tarhunta’s mother prostrated herself at Muršili’s feet, Muršili relented and agreed, for the old mother’s sake, to accept Manapa-Tarhunta as his vassal once again. Never again would the western lands rise to become a single, independent kingdom. Muršili broke up that kingdom into three independent lands. In Šeha River Land and Appawiya he installed Manapa-Tarhunta. He then moved on to Mira, where he installed Mašhwiluwa as the ruler of all of Mira and Kuwaliya and fortified the cities of Aršani, Šarawa, and Impanna. He made a special point to remind Mašhwiluwa how he had supported him where his father Šuppiluliuma had not been able to, and how he had furthermore fortified towns for him. Then, declaring the men of Mira untrustworthy, he granted to, or perhaps more accurately, imposed on Mašhwiluwa a 600 man bodyguard. In the land of Hapalla, Muršili installed a man name Targašnalli. In this land Muršili installed Hittite garrison troops that Targašnalli was responsible for supporting and treating well. We further know that in the far northwestern corner of Anatolia Muršili made a treaty with a man named Alakšandu in the kingdom Wiluša (HDT #13). This name invokes obvious comparison to “Alexander”, and this image is of course further enhanced by the probable identification of Wiluša with “Ilios”, from which Homer’s Illiad takes its name. This “Alexander of Ilios” should not be equated with the Homeric Alexander (Paris) of Ilios responsible for the Trojan War, but here the Hittite evidence clearly provides a real cultural background for the fantastical epic. That the name Alexander was not uncommon in the west is suggested by the finding of the feminine form of this name in a Mycenaean tablet where it is written A-re-ka-sa-da-ra, and possibly its masculine form in A-re-ka-[sa-do-ro]. (YEAR 5) In his 5th year Muršili moved back into the Kaškan territories. He first marched against Mt. Ašharpaya. The Kaškans in this region had cut off the roads which led to the province of Pala. Cutting off Pala would have also cut off the province of Tummanna. So he marched and successfully conquered them. He then moved eastward to the land of Šamuha, where he stayed in the city of Ziulila. From there he moved on against the Arawannans, who had been attacking the land of Kaššiya since the days of his father. Muršili again proved successful. After this victory, he returned to Hattuša. (YEAR 6) The next year was a year of light activity in terms of Muršili’s campaigning. Since the days of his father, the Kaškans of Mt. Tarikarimu in the land of Zihhariya had been raiding Hatti. So Muršili now returned the favor and raided them and burned down their land. After this, he returned to Hattuša and campaigned no more that year. (YEAR 7) The beginning of this year is very poorly understood. This is very unfortunate, because it was a very important year. A Hostile Egypt Now here at the beginning of Muršili’s 7th year we find fragmentary references to Egypt. The men of Egypt and Hatti both seemed concerned with the men of Nuhašši. King Tette of Nuhašši rebelled against Muršili with the aid of EN-urta of Barga. But Muršili had another partisan of Barga on his side, Abi-radda. It is possible that Egypt had a hand in Nuhašši’s rebellion. Since Kadesh, too, seems to have revolted, it is possible that it went over to Egypt. Muršili sent Mr. Kantuzzili to Šarri-Kušuh in Kargamiš to attack Nuhašši, and, should the King of Egypt have come, he promised that he himself would also come. But someone defeated the Egyptian troops, so that they did not come. The situation, although unclear, seemed to be growing more and more unstable for the Hittites. A King of Kaška Muršili did not go against Nuhašši himself because a new and completely novel threat appeared in the Kaškan lands. A Kaškan named Pihhuniya of the land of Tipiya - active in the time of Šuppiluliuma - united the Kaškan lands under him and ruled them as a king - a situation which Muršili greatly marvelled at,

Pihhuniya continually led his forces against and finally captured the Upper Land and the city of Ištitina, turning it into his “pasturage.” Which such a serious Kaškan menace, Muršili had to turn his attention to the north. He sent a message demanding that Pihhuniya return what he had taken. But Pihhuniya was not interested in listening to Muršili’s threats,

This was not a promise that he managed to keep. Muršili marched into the Upper Land and attacked Pihhuniya, retaking all of his lost territory. As he retreated Pihhuniya resorted to a scorched earth policy against the Great King by burning down the towns which he had captured. But Muršili simply rebuilt them and continued on into the land of Tipiya, which he burned down in turn. Eventually, Pihhuniya’s will buckled, and he came to Muršili and prostrated himself at Muršili’s feet. Muršili carried him off to Hattuša, and so ended the career of the only known Kaškan king. The news in Syria seemed good, too. Šarri-Kušuh had managed to defeat an enemy (undoubtedly connected with Nuhašši in some way) while Muršili was off in the north. But the good news would not last. Muršili came out of Tipiya and settled in the city Ištitina in order to guide the reconstruction of it and the other fortresses that Pihhuniya had burnt down. While there, he made a poorly timed decision to pick a fight with Anniya, the King of Azzi and Hayaša. More Problems During the final campaigns of Šuppiluliuma I in the Hurrian lands, some Hittite civilians had fled into the land of Azzi. After his victory over Pihhuniya, Muršili decided that it was time to get them back. So he sent a letter to Anniya demanding the return of his subjects. Anniya could hardly have viewed this letter as anything less than a declaration of war, and he duly refused Muršili’s “request”, and launched an attack on the land of Dankuwa. It was all the excuse that Muršili needed. (YEAR 8) Muršili launched an attack on the city of Ura, a strongly fortified border town belonging to Anniya. This seems to have been sufficient to cow the men of Azzi, who sent a letter to Muršili promising to return the civilians Muršili had demanded. Unfortunately, they failed to do so. When Muršili wrote to Anniya complaining about this, Anniya replied that he had not been compensated for the Hittite civilians that he was being asked to return and for his own civilians who had been taken away to Hatti. For these reasons he once again refused to return the Hittite civilians who were in his land. Meanwhile, there were problems in the land Pala. Hutu-piyanza, who had conquered Pala in the reign of Šuppiluliuma I, was now governor of Pala and was at war with the city of Wašumana. Muršili responded to this by sending Mr. Nuwanza, the Great Wine Man, to his assistance. Together Hutu-piyanza and Nuwanza attacked, conquered, and burned down the city of Wašumana. The tensions in the north would have to wait, because “at that time the Hepat of Kummanni troubled me regarding the Festival of Calling Out,” and so Muršili’s presence was required in Kizzuwatna. So Muršili placed Nuwanza in charge of his northern operations, and he himself set off for Kummanni. Unfortunately, the Azzians saw this as an opportunity, and they used it to attack the cities of Ištitina and Kannuwara. Already weakened by the devastation caused by Pihhuniya, the city of Ištitina fell and was destroyed. Kannuwara managed to hold out and the Azzians were forced to lay seige to it. Death of a Valued Ally (YEAR 9) The problems in Nuhašši seem to have been related to a revitalization of Assyria. Whereas previously the Assyrians avoided contact with Hittite armies, now they seem to have begun attacking Kargamiš itself. So even though there were still problems with Nuhašši, when Muršili went to Kummanni to celebrate the Festival of Calling Out, his brother Šarri-Kušuh joined him there. It would be the last time the brothers were together. While in Kummanni, Šarri-Kušuh fell ill and died. The rites of death were performed in Muršili’s presence. It was a significant loss. Šarri-Kušuh had been Muršili’s most valuable support in the nine years of his reign, and he was also a great force for stability in Syria. With the war against Nuhašši dragging on, it was a bad time to lose such a strong personality. While he was busy in Kummanni, he sent out a man named Kurunta to deal with Nuhašši. He gave him instructions to destroy Nuhašši’s grain. Kurunta went forth to obey his king. While he was in Syria he lay seige to the city Kadesh, which had also rebelled (Amurru, still under Aziru’s rule, remained loyal). Aitakkama still ruled in Kadesh, but his time had come. When his son, Ari-Teššup, saw that the city’s grain supply was dwindling, he turned on his father and killed him. He then returned Kadesh to the Hittite fold, and he let Kurunta up into the city. Muršili was also informed about the seige of Kannuwara while he was in Kummanni. His solution to this problem was to instruct Nuwanza to relieve the beseiged city. Unfortunately, when Nuwanza took the omens before the campaign, they were unfavorable. So Nuwanza sent a message to his king informing him of the problem. With Anniya beseiging Kunnawara in the north, the Assyrians attacking Kargamiš in the south, Nuhašši in a state of unrest, and now the death of his brother, Muršili was nearly at his wits end. He was reluctant to leave Kargamiš in a dangerous state of transition for fear that the Assyrians would take advantage of the opportunity. So in a flurry of activity, he delegated authority. He took omens of his own concerning the relief of Kannuwara, and these turned out favorable. So when he left Kummanni and set out for the city of Aštata, he sent prince Nana-ziti to Nuwanza with news of the favorable omens. At Aštata he built up the fortifications. While in Aštata Ari-Teššup of Kadesh was brought before him and officially accepted as a Hittite vassal. Muršili then moved on towards Kargamiš. While en route, Nana-ziti returned to him and reported that Nuwanza had successfully relieved the seige of Kannuwara and that a large number of Azzians had been killed and captured. With this good news, Muršili entered Kargamiš in order to handle the succession to its throne. He duly installed Šahurunuwa, Šarri-Kušuh’s son, as the new king of Kargamiš. Shortly after this he swore in Talmi-Šarruma as king of Halap. With Syria properly organized, Muršili left Kargamiš and moved north to the city of Tegarama. But the year had grown short, so he chose not to march against Azzi. Instead, he marched to Harran, where he made provisions for his troops, and then moved on and attacked the city of Yahrešša. He made a surprise attack on this city at night and burned it down. He then moved on against the land of Piggainarešša. He attacked the Kaškans there, and he burned down the land. After this, he returned to Hattuša, and, finally, he wintered in the city Hakpiš. (YEAR 10) The next year, he finished his campaign against Azzi. The Azzians did not want to face Muršili in open battle, so they took to their citadels situated in places difficult to access. Muršili only dealt with two of those places, Aripša and Duškamma. Aripša lay on a rocky promontory jutting out into the Black Sea. In spite of this, he successfully captured it. The people of Duškamma heard this and gave themselves up to Muršili. This campaign took most of the year, so Muršili returned to Hattuša for the Year Festival without first organizing Azzi. (YEAR 11) In the next year, he returned to Azzi and organized it. (YEAR 12) Revolt of Mašhwiluwa. See below. His other campaigns seem to deal mostly with Kaška and Pala/Tummanna. Muršili writes Annals: Muršili wrote extensive annals both for his father (The Deeds of Šuppiluliuma, edition by Güterbock) and for himself. Possibly made a treaty with Horemheb of Egypt. Muršili’s Speech Loss: As a child, a thunderstorm frightened him and he couldn’t speak for awhile. Later, in a dream, the god caused him to lose his voice again. Priests from Ahhiyawa and Lazpa (= Lesbos) were sent to assist him. A ritual involving a scape-bull was performed in Kummanni for the Stormgod of Manuzziya (in Kizzuwatna), who had been established as the god at fault.

10 Year Annals:

(See Annals of Muršili II) A Plague in the Land The plague which took the life of Muršili’s father and brother continued to haunt the land of Hatti twenty years after Šuppiluliuma brought the infected Egyptian prisoner’s back to Hatti. It weighed heavily on Muršili’s conscience, so that he ultimately seems to have becomed obsessed with determining its cause and eliminating it. Several of his works deal with the topic. It ultimately found its way into the king and queen’s daily prayer to the gods. The Storm God Telipinu and the Sun Goddess of Arinna in particular received daily prayers which were essentially identical to each other (that to Telipinu is given below). Since Muršili himself could not continually devote himself to the task, he assigned priests to do it for him, (The following comes from ANET pp. 396f with changes of language. This must be replaced by a direct translation!)

The first task was to lure the wandering god to the temple so that he might receive the prayers,

Muršili then resorted to language which sounds strikingly similar to the long past plea by Arnuwanda I and Ašmu-Nikal about cult cities lost to the Kaškans,

After this very traditional argument for receiving divine favor from the god, there follows a rather unorthodox hymn for the god Telipinu. Hymns are known from Mesopotamian religious practice, but are somewhat out of place in Hittite religion, and so the inspiration for this hymn was presumably Mesopotamian,

After shamelessly flattering the deity so, the royal couple turned to the question of favors. The requests are mostly generic, but pressing problems, such as the long standing plague, found their way into the prayer,

To all of this the assembled witnesses of this daily prayer shouted, “Let is be so!”, the Hittite equivalent of “Amen!” Muršili later installed Aziru’s son DU-Tešup in Amurru, and later his grandson Tuppi-Tešup. The Hittites apparently took Mitanni from the Assyrians during Muršili’s reign as well. Muršili and Tawannanna: The Tawannanna Mal-Nikal was accussed of cursing Muršili’s wife which resulted in her death, so she was deposed and exiled to estates. So she began to curse Muršili himself. She seemed to try to get herself reinstalled in her priestess office, which is probably the purpose of Muršili’s text which relates the above information. Muršili was telling the gods why they should not reinstall her as Tawannanna. Was the will of the gods to be determined by taking an oracle? The reign of Muršili also saw the beginnings of a problem which would color the rest of Hittite history. Or more precisely, a problem who would color the rest of Hittite history. This was namely his youngest son, Hattušili. As a young man being raised in the imperial household, his earliest known position is that of a chariot driver. At this time in his life a serious illness struck the young prince, and the goddess Šaušga is said to have sent a message to Muršili by means of a dream in which Muwattalli, another of Muršili’s sons, appeared to him. In the dream Muwattalli conveyed to his father that Hattušili was not destined to live unless Hattušili was given over in servitude to Šaušga as her priest. Muršili accordingly did so, and Hattušili is said to have recovered from his illness. While the goddess may have been ultimately responsible for his recovery, she apparently worked through a human agent, as Hattušili would reveal much later in his life,

Hattušili appears to have remained quietly in his role as Priest of Šaušga of Šamuha for the rest of his father’s reign. Foreign Relations Amurru: Muršili installed Duppi-Tešup as king of Amurru. Arzawa: He conquered it and gave it to Piyama-Kurunta. Mira-and-Kuwaliya were given to Mašhwiluwa, the Šeha River Land and Appawiya were given to Manapa-Tarhunta, and Hapalla was given to Targašnalli. See The Treaty with Alakšandu of Wiluša. Wiluša: Kukkunni took Alakšandu for adoption and as his successor. See The Treaty with Alakšandu of Wiluša. Ugarit: First brought into the fold by Šuppiluliuma I. Šuppiluliuma I had a treaty with Niqmaddu. Muršili II made one with Niqmepa, son of Niqmaddu. Mira-and-Kuwaliya: Mašhwiluwa - In the fourth year of his reign, Muršili defeated Arzawa and divided up the land into new vassal states. For the kingship of Mira-and-Kuwaliya he installed Mašhwiluwa, an brother-in-law of his by marriage who had previously ruled there in the time of Šuppiluliuma before being driven out by his brothers (See under Šuppiluliuma I). Mašhwiluwa had no son, so with Muršili’s approval he adopted his nephew Kupanta-Kurunta as his heir. In spite of his long and close relations with the Hittites, Mašhwiluwa proved to be an undependable ally, rebelling against Muršili and convincing the Hittite city of Pitašša to join him. Muršili marched to Šallapa and sent for Mašhwiluwa in an attempt to find a peaceful settlement. Mašhwiluwa refused to come into the Great King’s presence, because he “saw his offense”, and fled to the land of Maša instead. Muršili marched against Maša and destroyed part of it. He then sent to Mašhwiluwa’s hosts, insisting that they return the errant vassal to him, and threatened to destroy them and their land if they did not. The threat worked, and the Mašaeans seized Mašhwiluwa and sent him to the Great King. Muršili treated his troublesome uncle with leniency and installed him as the ruler of a “sacred city” on the Šiyanta River. This seems to suggest that he became the priest of a town which was ruled by the local cult. Making errant relatives into priests is a practice that we have witnessed many times in Hittite history. Kupanta-Kurunta -

With this dire threat permanently established in his treaty, to be read out loud thrice yearly, Kupanta-Kurunta was duly installed by Muršili as the king of Mira-and-Kuwaliya in Year 12. This ruler seems to have remained loyal. Egypt: (See Murnane (1990)31-38)

These words come from the Egyptian heiroglyphic version of the treaty between Rameses II of Egypt and Hattušili III of Hatti. This is virtually the only evidence that there were two treaties made between the Hittites and Egyptians before this final, lasting treaty. The treaty present at the time of Šuppiluliuma I is believed to be a reference to the Kuruštama treaty mentioned in the Deeds and in Muršili’s plague prayer. The treaty present at the time of Muwattalli is more difficult. It was probably enacted during the Muršili’s reign. It certainly was not enacted during Šuppiluliuma’s reign, Arnuwanda’s reign was probably far too short, and according to Murnane the language used indicates that the treaty was probably already in force during Muwattalli’s reign. Other evidence for this second treaty comes from earlier in the same treaty quoted just above, where Hattušili claims that “the god did not permit hostility to occur between them by means of an arrangement. But in the time of Muwattalli, the Great Prince of Hatti, my brother, he fought with [...], the great ruler of Egypt.” (Murnane (1990) 37). This passage also suggests a treaty made during Muršili’s reign. Murnane presents Horemheb as the strongest candidate, although he also admits the weaker possibilities of Rameses I and Sety I. Muršili II or his father, Šuppiluliuma I, refounded Emar. Cause of Plague:Oracle: Šuppiluliuma I killing Tudhaliya the Younger. |

|

| Some or all info taken from Hittites.info Free JavaScripts provided by The JavaScript Source | |