| Labarna II King of the Hittites | |

|

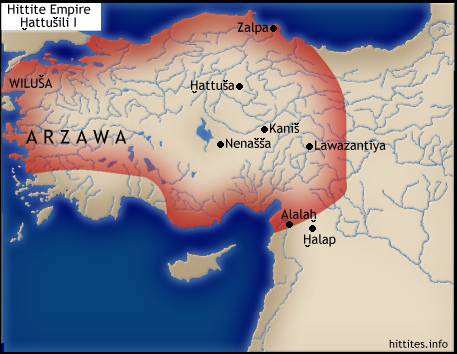

Labarna II was the first king of the Hittite empire, reigning in Hattusa (while the earlier kings had been at Nesa), and taking the throne name of Hattusili I on that occasion. He reigned ca. 1650–1620 BC (middle chronology). He is the earliest Hittite ruler for whom contemporary records have been found. In addition to "King of Hattusas", he took the title "Man of Kushara", a reference to the prehistoric capital and home of the Hittites, before they had occupied Nesa. A cuneiform tablet found in 1957 written in both the Hittite and the Akkadian language provides details of six years of his reign. In it, he claims to have extended Hittite domain to the sea, and in the second year, to have subdued Alalakh and other cities in Syria. In the third year, he campaigned against Arzawa in western Anatolia, then returned to Syria to spend the next three years retaking his former conquests from the Hurrians, who had occupied them in his absence. If Labarna I set an auspicious precedent for the fledgling Hittite dynasty, Hattušili I did not fail to carry the torch. While Labarna I remains a shadowy figure in the annals of history, Hattušili I did not go quietly into oblivion. The armies he led into battle would slash their way into the histories of foreign empires, and Hattušili himself left his mark in the archives and memories of the Hittites and, thereby, us. All of this in spite of the fact that he was not even Labarna's son. In his own Annals he a describes himself as “son of the brother of Tawannanna”. Obviously, this means that Hattušili was not a son of Labarna I, but rather a nephew of the queen. But the Hittite succession depended upon the male lineage, not the female. So why did Hattušili declare for the ages that he was related to the queen rather than to the king? The best answer comes from the one known condition whereupon the right to the throne came from the female side of the family:

Admittedly, this rule was only formally recorded several generations later, but all the evidence available to us indicates that at that time it was merely an official proclamation of an already prevailing custom. When we combine the evidence available to us from here and a few other sources, it seems likely that Hattušili's predecesor, Labarna I, was a son-in-law of PU-Šarruma who was married to “a daughter of the first rank”. He became the heir because the rebellion by the king's sons made them unacceptable for the kingship. This meant that it was Tawannanna who carried on the blood line of the Great King rather than Labarna. When Hattušili came to the throne, he wished to emphasize that he was truly of the royal line, a son of one of the disinherited princes, whom Labarna took as his own son by way of marriage - a custom known among the Hittites as antiyant-husbandship - and made the heir to the throne. The question then becomes, whose son was he? It has been suggested that he was the son of Papahdilmah, the rival who Labarna had to defeat in order to sit upon the Hittite throne. This is not necessary but at least has the advantage of historical precedent in another culture at another time (England). Whichever prince he was the son of, he was a true member of the Great Family and thereby brought its blood back to the throne of Hatti. Ironically, though, it means that Labarna I, the man who future Hittite kings considered the founder of their dynasty, was not actually of their genetic lineage! But what became of the sons of Labarna and Tawannanna? It is extremely unlikely that they would passively sit and watch their father's throne pass over to a cousin. After Hattušili came to the throne, his relation to Tawannanna, which had proven so useful for his succession, proved an impediment to his reign. For when he came to the throne, Tawannanna retained her position as Great Queen, and her aspirations for her own sons came into conflict with Hattušili's interests. In the end, no compromise proved possible, and he declared,

Hattušili thereby decreed the elimination of the lineage of the dowager queen from consideration for the throne. The way was now clear for his own sons. Rich Beal believes that the king referred to in the Zalpa Text (CTH #3.1) is Hattušili I. If so then Hattušili was responsible for the destruction of Zalpa. The Zalpa text outlines the course of conflict between the Hittite palace and Zalpa over three generations. The text is normally ascribed to Muršili I. His reign was similar to Labarna I's in that he was supposedly a successful leader who expanded Hittite territory and sent forth his sons to rule conquered lands. He expanded the Hittite borders to the sea. See the The Proclamation of Telipinu §§5-6. He seems to have expanded the state so that it encompassed Cappadocia as far as the Black Sea in the north and Kizzuwatna in the south. The Military Campaigns of Hattušili I, According to His Annals (From The Annals of Hattušili I)Year 1 The campaigns of his first year seem to have all taken place within Anatolia, although the Zalpa mentioned in his text was probably located in southeastern Anatolia, rather than the more famous Zalpa to the north. He began by campaigning against the city of Šanawitta/Šahwitta. (The “Šanahwitta” in which PU-Šarruma declared Labarna I to be his successor.) He didn't capture the city, so instead he destroyed its lands and garrisoned troops in its vicinity. Then he moved on and attacked Zalpa/Zalbar and destroyed it. Afterwards three MADNANU-chariots (A type of chariot which apparently had four wheels and a flat bed, see CAD sub madnanu and majāltu) which he had captured he dedicated to the Sun Goddess of Arinna. It's questionable how useful these four wheeled chariots would have been in warfare. The two wheeled light chariot began rapidly supplanting it as far back as the karum Kaniš period. By now it must have been relegated to the position of a hallowed prestige item. Even in this capacity it would not last much longer. In addition to these chariots, he gave one silver ox and one silver fist to the temple of the Storm God. The rest, referred to in the Akkadian copy as “its (i.e Zalbar's) nine deities”, he gave to the temple of the goddess Mezulla. Year 2 (Syrian campaign) This year Hattušili moved into Syria. His first target was Alalah, an important city that guarded the eastern end of a strategic mountain pass. At this time Alalah was ruled by Ammitaqu, who was himself in vassalage to Hammurapi of Halap. Hattušili destroyed this city (Archaeologically this destruction marks the end of Level VII), burning down both the palace and the city. After this destruction, Hattušili moved on against Waršuwa/Uršu. The Seige of Uršu Hattušili's seige of the city of Uršu inspired a rather interestng text named by scholars today, appropriately enough, The Seige of Uršu. The Hittite original is lost to us, but a fragmentary version translated into the Akkadian language (see Beckman (1995) 27) has been discovered. The document is clearly of a literary nature, so we would have difficulties trying to separate the facts from the fiction, but it is worth discussing this text for what it reveals about Hittite literature. Unfortunately, both the beginning and the end of the text have been lost, so we must open the story in its middle and close it before its conclusion. Where the text begins, the Hittite king, who is situated in the city of Lawazantiya, is giving certain orders to two of his military officials, named Šanda and Menaniya. These officers appear to have previously failed their king in battle, and they were being instructed on how to eliminate their offense. Although his specific commands are difficult to comprehend (Beckman suggests that they were meant to be humorous), the bottom line was clear;

His commanders dutifully replied,

Unfortunately, his officers did not meet his expectations,

But there was nothing for it but to carry on, and try a new approach. So the king commanded,

The seige works were to be constructed over the course of the winter. Šanda was summoned to the king's presence in Lawazantiya to inform the king of conditions in the enemy's territory. The king is informed that "the servant" (i.e. the king of Uršu?) will fall into Hittite hands if Uršu came to ruin, but that for the moment the king of Kargamiš was posting watches in the mountains. The strong position of the king of Kargamiš is blamed on a “foul deed” done by two men, Nunnu and Kuliat. These two men were probably Hittite, and their “deed” was probably the failure to act appropriately in some way in an earlier part of the text which is lost to us. This is unfortunate, since a man named Nunnu, who may be the same man mentioned in this text, also appears in the so-called Palace Chronicles, where he is punished for corruption. There follows a long, obscure section in which the king seems to lecture his officers about how he sees through the deceptions of his enemies. The Hurrian lands were divided, and the Hurrians, referred to as the “sons of the Son of the Storm God” (i.e. servants of a ruler, who is himself the servant of the Storm God?), were fighting with each other over kingship. The Hittite officers failed to take advantage of the situation, and the king berated them,

Instead of fighting, the Hittite officers only sang war songs and hesitated, just as a man named Tudhaliya had the previous year. Exasperated, the king makes them promise to go and burn down the city gates and engage in battle. The officers happily replied,

They did nothing. Instead, the enemy attacked them, and many were killed. Angered yet again, this time the king instructed them,

Even this could not be done properly by the officers. A fugitive came out from the city and revealed to the king that a servant of the ruler of Halap had entered the city five times, that the servant of Zuppa was in the city, that the men of Zaruar went in and out, and that the servant of the “Son of the Storm God” (the ruler of Uršu?) also went to and fro, bringing precious goods to the Hurrians to entice them to come to the city's aid. Just as the king begins to lecture his officers again, the text breaks. What can be made of this text? In its broken state, and without much of the cultural baggage that would make this text clearer, we may take it as a simple effort to extol the virtues of the king. But this text is probably a much more sophisticated work. The text deals with a subject that would be important to a military aristocracy - the beseiging of a city. But this knowledge is not instinctive, it must be learned - and this text seems to reveal the proper way to successfully lay seige to a city. It does extol the king in the sense that only a wise man would know the proper way to do this, and the king has been cast in this role. This is reminiscent of the later instruction texts for officials, which were said to be the words of the Great King himself. More than that, it reveals the proper way to respond to setbacks (always the fault of the officers, never the wise king). The only real difference between this text and the later Hittite instruction texts is that here the knowledge is made more entertaining by wrapping it up in an epic tale. The story, in turn, which was based on a real event, reminds us of another Old Hittite text, namely the Palace Chronicles, a series of lessons that were taught by way of anecdotes. The seige process revealed in this text is clear. When the text (as we have it) begins, we may be looking at the end of an attempt to capture the city by destroying its army in open battle. This having failed, it became neccessary to make an open attack on the city. But this failed when the battering ram broke. So the Hittite king gives instructions on how to lay seige to the city. Judging by the text, this decision would have been made when winter approached and the campaigning season drew to a close. This is itself interesting because later annals of Hittite kings do indeed seem to follow this pattern. In the central section, if we try to understand the lessons of the obscure anecdotes rather than fit them into the story, reveals that the enemy could be expected to post scouts, that the Hittites had to gather their own intelligence as well, that in the case of betrayal, local resources could be depended upon, and that the divided state of the enemy should be taken advantage of. Moving out of this otherwise obscure section, it then becomes clear that, according to Hittite military wisdom, he who hesitates is lost. A bit of advise which continues to hold true even today. Finally, just before the text breaks, the importance of completely cutting off the city is revealed, and the consequences of failing to do so. In short, this text seems to be a bit of wisdom literature. Not in the philosophical sense, but in a way that would have had immediate significance to a caste of men who were in a perpetual state of war. It outlines the combined wisdom of the Hittites on how to successfully capture a city. All of it was wrapped up in an interesting (and probably popular) story which further extolled the wisdom of the king. This is a literary expression of the architectural principle common today, namely “form follows function”. The real reason for the Seige of Uršu text must, unfortunately, remain speculative. Returning to our narrative, the capture of Uršu remained simply an episode presented in Hattušili's annals. After Uršu he moved on and attacked Ikakali and finally Tašhiniya/Tišhiniya. A just published letter from Hattušili I (“Labarna”) to a vassal king in Syria was written during this year's campaign (Salvini, Mirjo, SMEA 34 (1994) 61-80 + pics). Year 3 (Arzawa campaign) This year he marched against Arzawa, a land or kingdom in western Anatolia. This must have been a disastrous expedition, since he didn't capture any cities, and had to be satisfied with plundering cattle and sheep. This in turn must have resulted in a profound loss of faith in the king, since Hattušili's kingdom virtually disappeared behind his back. The Hurrians (referred to as "the enemy from Hanigalbat" in the Akkadian version) invaded his lands and all other lands revolted, leaving him only Hattuša. With the help of the Sun Goddess of Arinna, he began to reconquer the lands. First he went against Nenašša (= Turkish Aksaray), whose men opened its gates to him when they saw him coming. Then he had to fight two battles against Ulma/Ullumma (located to the south), which he destroyed and scattered cress over (i.e. left it abandoned). He then returned to the north, bringing booty with him. He carried off seven deities, one silver ox, and the goddess Katiti of Mt. Hapilanni, which he gave to the Sun Goddess of Arinna. The booty from the rest of the temples he gave to the temple of the goddess Mezulla. He then went to Šallahšuwa (to the south or southeast). Some sort of internal revolt must have taken place within the city, since the city set itself on fire and the citizens made themselves into Hattušili's subjects. After this, Hattušili returned to Hattuša. Year 4 (2nd Northern Campaign) This year began with a six month return campaign against Šanahuitta/Šanahut, located to the north or northeast of Hattuša. In the sixth month, Hattušili successfully destroyed it. He dedicated booty from the campaign to the Sun Goddess of Arinna. He then defeated the chariotry of the land of Abbaya. He then marched against the city of Parmanna, which was the leader of an anti-Hittite coalition. Parmanna did not offer resistence and opened its gates to Hattušili. Finally, he marched against and destroyed Alahha (location unknown). Year 5 (2nd Syrian Campaign & the Crossing of the Euphrates) Hattušili began this year by destroying the city of Zaruna. He then fought against the armies of Haššu (Mama? See under Waršama), a Hurrian city located to the east of the Euphrates. Hammurapi II, son of Yarim-Lim III and king of Yamhad (Hitt. Halap), sent Zukraši, the “Commander of the Regular Troops”, and Zaludi, the Chief of the Umman-manda troops, to Haššu's defense with troops and chariots. Hattušili's army defeated the combined troops of Halap and Haššu in the Adalur Mountain (in the Amanus range), crossed the Euphrates (The first Hittite king to do so), destroyed the city of Haššu(wa) itself, and brought its booty back to Hattuša. He gave booty to the temple of the Storm God. He then went on to destroy Tawanaga and cut off its king's head. Then on to destroy Zippašna. He brought its gods to the Sun Goddess of Arinna. He then went against Hahhu. It took him three battles outside of the city gates before he was finally victorious. He brought back booty and gave it to the Sun Goddess of Arinna. He compared his crossing the Euphrates to the achievements of Sargon, and points out that even Sargon couldn't destroy Hahhu, but he did. At this point, the text ends.

The empire after the conquests of Hattusili I. The conquest of Arzawa, including Wiluša, is historically attested. The Lukka Lands and Pamphylia have been left off due to uncertainty rather than definite knowledge. The extent of territory controlled to the north, east, and south is uncertain. At some point in his reign, perhaps during the campaign of Year 3 (Although this seems unlikely), Hattušili successfully subjugated Arzawa, including Wiluša. At some later, unspecified point in time, Arzawa and Wiluša freed themselves. Arzawa became hostile to the Hittites, but Wiluša remained friendly. See the Treaty with Alakšandu of Wiluša. Land Transactions The most important source of wealth in Hatti was land. This made the transfer of land from one party to the other a significant transaction, particularly when it involved high ranking members of Hittite society. It is during the reign of Hattušili which we find the appearance of documents, sealed by the king, which record the transfer of land from one individual to another. Typical of the evolving Hittite document style, we even receive a bit of the history involved in the transfer of the land. The tablet, believed to have been written during Hattušili's reign, was discovered not at Hattuša but rather at the site of İnandik. This in spite of the fact that the document itself claims to have been issued in Hattuša. However, İnandik is not very far from Hattuša and thus possibly within its administrative district (so Easton (1981)). It records that Tuttulla, the governor of Hanhana, took a man named Zidi as his son by making him the antiyant-husband of his daughter Zizzatta. He then gave him something, not entirely clear, but given the nature of the document it was probably a portion of land. This, however, seems to have caused some problems with his natural son, a man named Pappa. At this point, the Great King became involved. Probably in an attempt to resolve the dispute, he handed Pappa over to the Queen of Katapa, a goddess. We learn from the Palace Anecdotes that Pappa became an uriyani-temple official. The dedication of Pappa to the service of the goddess no doubt included the transfer of temple land to his authority, presumably thereby ending the conflict. The king emphasized the finality of his decision by forbidding either Pappa or his descendents to dispute the case with either Zidi or his descendents. It's interesting to note that several names which appear in this land grant document also appear in the Palace Anecdotes. Both Zidi and Pappa are subjects of anecdotes. Among the witness list to the land grant document appears prince Ašgaliya, and Ašgaliya, Lord of Hurma, appears among the anecdotes. Of course, the mere reoccurence of a name does not guarantee that they are the same people. In fact, in the land grant document, as well as having Ašgaliya the prince, the scribe who wrote the tablet also bore the name Ašgaliya. Nevertheless, the overlap of more than one name, the fact that Pappa appears in a temple setting in both documents, and the fact that we are dealing with the upper reaches of Hittite society in both documents is certainly strongly suggestive that we are indeed dealing with the same people. The Palace Chronicles The king's justice in the Old Kingdom could be harsh. The Great King had arbitrary power of life and death over his subjects, and his justice could be fierce. One of the Old Kingdom anecdotes, which probably speaks of Hattušili when it speaks of "the father of the king", tells the case of Nunnu, the Man of Hurma (the title of an official) in Arzawa. Nunnu had been taking for himself silver and gold which was owed to the king. The Man of Huntara informed on him, and so Nunnu was removed from his post and brought up to the king for punishment. Nunnu was to be replaced by another man named Šarmaššu. The king rendered Nunnu's punishment and administered a potent warning to Šarmaššu at one and the same time. The Gold Spearmen brought the two to Mt. Tahaya, where,

Such was the fierce and arbitrary nature of the Great King's power. To ensure that his justice had been properly administered, the king wanted to know that the blood of the victim had spattered both men - and he expected to see this evidence for himself:

While an unpleasent story, this anecdote reveals to us two fundamental princples of Hittite justice. The first is that the entire family could be held accountable for the sins of one of its members. In this case, it was not Nunnu himself who was killed for his crime, but rather a member of his family. Some three and a half centuries later this principle can still be seen to be in full force, when Great King Muršili II would warn the son of a rebel vassal, "Are you... not aware that if in Hatti someone commits the offense of revolt, the son of whatever father commits the offense is an offender too?" The second principle seen here is that an in-law was considered to be a true member of the family. It is this principle that made the antiyant-husband possible. This principle was enshrined in a myth in which a man who's father-in-law was about to be killed by his true father pleaded with his father to kill him as well, and his father complied. "I Have Now Become Ill" Hattušili's war against Halap would forever reduce the status of that once mighty city, but this energetic ruler would not live to see the Hittites' ultimate victory there. He received a mortal - if not immediately fatal - wound in a battle against that city. Back in Hatti he seems to have concluded that his nephew and adopted son Labarna, his chosen successor, did not show a proper concern for his welfare and so was no longer fit to replace him on the throne,

In spite of Hattušili's attempts to properly instruct him, Labarna would only listen to the words of his brothers, sisters, and especially his mother, who Hattušili repeatedly refers to as "the snake". Eventually Hattušili could take this disobedience no longer, declaring,

So he was exiled to an estate and given a position as a priest. Hattušili's problem with his sister's son Labarna was not the first time he had had such difficulties. In his Succession Proclamation (Extant copy is NH, the original was OH, perhaps copied by Hattušili III?), the mortally wounded Hattušili outlined all the problems he faced when establishing his successor. His own son Huzziya had been incited to revolt by the great houses of Tappaššanda, who desired tax exemptions. Hattušili successfully suppressed his son's uprising, but he was clearly no longer a fit candidate for the succession. Subsequently in Hattuša a daughter of his was incited to conspire against him so that her son could take the throne. As a result Hattušili exiled her to an estate. Then came Labarna, who, as we have seen, also proved himself unmerciful and unworthy, and followed his mother's, brothers', and sisters' advise rather than Hattušili's. Finally, an apparently quite young Muršili (he was not to be permitted to go on campaign for three years), who was one of Hattušili's grandsons, was selected as the new successor. See The Succession Proclamation of Hattušili I. Foreign Relations Aleppo: (Halap, Kingdom of Yamhad) Bagged Alalah, a vassal city of Yamhad which protected the eastern end of a strategic pass between Anatolia and Syria. He did not, however, capture Aleppo. By inflicting a heavy defeat on Yamhad's army and taking some of its territory, he ended the Great Kingship of Halap (Yamhad) (i.e. reduced its status to that of a minor kingdom). Hattušili may have died as a result of a campaign against Halap. Arzawa: Arzawa was the general Hittite term for western Anatolia. It could also be a specific kingdom. The Arzawa lands consisted of five major kingdoms, which sometimes were and sometimes were not united, depending on the time. These were the lands of Arzawa, Mira, Hapalla, Šeha River Land, and sometimes Wiluša. The lands of Kuwaliya and Appawiya are also named in The Treaty with Alakšandu of Wiluša. Wiluša (Homeric (W)ilios) was probably located in the extreme northwest of Anatolia and perhaps included Homeric Troy (Hittite ‘Taruiša’), although Troy might have been a land in its own right. Arzawa had a capital at a city named Apaša, which was probably Ephesos, and thus Arzawa was centered on the middle of the western coast of Anatolia. As far as our evidence allows us, all of these lands appear to have spoken Luwian (See Calvert Watkins (1986)). Hattušili raided Arzawa (Copy A says Šahuitta) in Year 3, taking cattle and sheep. The fact that he does not mention the destruction of any cities would seem to indicate that this campaign was a disaster. But at some point, he probably gained at least temporary dominion over the Arzawa lands, including the land of Wiluša. Wiluša: Probably Greek (W)ilios. The Greeks believed that Ilios was a city and Troy the land around it. How this fits the Hittite description of both Wiluša (Ilios) and Taruiša (Troy) as lands (KUR URU's, lit. "land of the city of...") is unclear (See Güterbock (1986) 40f.). Muwattalli II said, in The Treaty with Alakšandu of Wiluša, that "Labarna" had conquered Wiluša (Located in northwestern Anatolia). This was probably Hattušili I, since he is known to have campaigned in Arzawa. Wiluša later freed itself, but remained friendly with Hatti, demonstrated by the regular sending of envoys to the Hittite king, whereas the rest of the Arzawa lands became hostile to the Hittites. See The Treaty with Alakšandu of Wiluša. Kizzuwatna: Already possessed by the Hittites: Beal (1986) 425, says that the fact that Hattušili's first attack in Syria was against Alalah, which controlled the eastern (Syrian) end of the Beilan Pass between Anatolia and Syria, can be taken as evidence that Kizzuwatna, at this time known as Adaniya, was already a Hittite possession. Zalpa: Located at the mouth of the Kızıl Irmak. Currently may be drowned under the waters of the Black Sea. Probably sacked by Hattušili. |

|

| Some or all info taken from Hittites.info Free JavaScripts provided by The JavaScript Source | |