| Hattušili III King of the Hittites 1275-1250 BC | |

|

He was the Son of Muršili II

(Contemporary with Adad-nirari I and Šalmaneser I of Assyria (See Peter Machinist (1987))) (Ascends to throne Year 14 to Year 17 of reign of Rameses II of Egypt. See Rowton (1960) 18) Hattušili's seizure of the throne sowed the seeds of the end of the Hittite Empire. But even in its slow demise the empire would remain a great power for a further two generations. In fact, it would see its greatest material splendour under the reign of Hattušili's son. How, then, can we speak of the the destruction of the empire at this early date? After all, Hattušili was hardly the first member of the Great Family to usurp the throne. What was so unique about his coup? A comparison with the coups of earlier rulers will reveal an extremely important difference: armies. Without any known exceptions, previous usurpers came to the throne through assassination, not civil war. The reason for this was fairly straight forward. Until the empire, armies were led by generals who were appointed by the king on a campaign-by-campaign basis. Therefore a general had little opportunity to build up a power base against his sovreign. The vassal treaty system would ultimately undermine this system. Šuppiluliuma I introduced the widespread use of the treaty to control vassal kings. His reasons were undoubtedly sound. He made treaties with kings of distant lands which he could not reasonably incorporate into the closely controlled provincial system. But, from the very beginning, this system demonstrated a dismal record for maintaining a vassal's loyalty. Even worse, as we have seen, this system was internalized by Muwattalli II when he created the kingdom of Hakpiš for Hattušili. This may have meant a reduction in imperial expenditure on this deeply troubled region, but it also meant that there was now an army whose loyalty was centered around the vassal king, rather than upon the Great King. Whether or not he realized it, Muršili III undoubtedly had the right idea when he tried to eliminate this threat to his authority. In the end, however, Muršili proved unable to undo the damage done by his father. Hattušili used the army of Hakpiš to defeat the imperial army and seize the imperial throne. Hattušili, however, does not seem to have been aware of the threat that his own actions were evidence for. For, as will be seen, the internalization of the treaty system would continue under his reign. For the moment, however, all he sought was to return the empire to the old status quo as it was under his brother's reign. In this vein, the family of Hattušili's old benefactor Mittanna-muwa was rewarded handsomely for its long-time support. Mittanna-muwa himself appears to have grown far too old to play any sort of active role in the government, but he had many sons whom Hattušili did not forget. Alihhešni became a halipe-functionary, the role of which is unclear. Walwa-ziti ("Lion-man") received his father's old position as Chief of the Scribes. Two other sons, Adduwa and ŠEŠ-ZI (reading uncertain) were also rewarded by Hattušili. All of these sons swore an oath of loyalty and support to Hattušili, Pudu-Hepa, and their descendents, in return for which Hattušili and Pudu-Hepa swore that the welfare and positions of the descendents of Mittanna-muwa would be perpetually maintained. Another man to benefit was Ura-Tarhunta who, as we saw, had sided with Hattušili against his own father, Kantuzzili. For this support, Ura-Tarhunta's house was exempted from taxation for his own lifetime and down through the generations as well. It was further stipulated that, even if some descendant of his should commit a crime which should cause his estate to be seized, it could only be given to another of Ura-Tarhunta's descendents. An Official Version of History While assassination may have once been common among the royal family, it seems to have gradually grown less and less acceptable. The last known assassination was that of Tudhaliya the Younger, the designated heir of Tudhaliya III. The last known Great King to fall at the hands of one of his subjects was Muwattalli I, who had been killed over one hundred and fifty years before Hattušili seized the throne. So there was no current tradition of regicide in Hatti, and moreover, the Great King seems to have taken on greater religious sanctity in the interim. This, along with his family ties and his obvious desire to appear magnanimous in victory, may have been what stayed Hattušili's hand in his treatment of his captive nephew. Instead of execution, Hattušili followed the long standing Hittite practice of banishment. Muršili was given fortified towns on the edge of the empire - in the land of Nuhašše - to rule over. Having removed his nephew far from the presence of the imperial city, Hattušili launched a vigorous propaganda campaign wherein he established the official justification for his revolt and for his usurpation of the throne. The first of the propaganda texts was probably the loyalty oath which the Men of Hatti were required to swear to the new Great King and, after his reign, to one of his descendents by Pudu-Hepa (KUB 21.37). In this oath they were specifically forbidden to seek after Muršili or his sons for kingship. This text also introduces all the elements of Hattušili's version of events that would reappear in his other texts. Speaking to the men of Hatti, he accuses,

Other official elements appear: how Hattušili took up Muršili when Muwattalli died and made him Great King, how Hattušili was loyal to Muršili, but Muršili broke his word to Hattušili and did wrong against him, so that Hattušili revolted against this oppression. The judgment of the gods made Hattušili victorious. All of these elements would be elaborated upon in other documents. Hattušili would never forgive Muršili, nor his old nemesis, Arma-Tarhunta. In later years, his son Tudhaliya reported that his father refused to take part in a ritual which would have healed the estrangement between Hattušili and the sons of those men. Muršili's defeat was the final crushing blow to the house of Arma-Tarhunta. Half of his estate had been dedicated to Šaušga of Šamuha during the reign of Muwattalli II when he had been found guilty of black magic and handed over to Hattušili. Now the plans of his son Šippa-ziti had come to ruin, and the remaining half of the family estate was seized and similarly dedicated to Šaušga of Šamuha. It is this occassion which inspired Hattušili to write his famous Apology, which has been the source of so much of our information about the reigns of Muwattalli II and Muršili III. The Apology is actually the text granting Arma-Tarhunta's estate to the cult of Šaušga of Šamuha. Hattušili has simply used the historical introduction, similar to those of vassal treaties, to promote his own version of his life and his conflict with Muršili III. In fact, the historical section was so greatly expanded that the actual grant only covers the final three paragraphs of the document. According to the Apology, stelas and grain storage facilities were set up in the houses and cities that previously belonged to Arma-Tarhunta. Šaušga was to be sacrificed to as "Šaušga the Exalted". Hattušili further dedicated the Bone House (i.e mausoleum) which he had built. He also installed his son, Tudhaliya, as the Priest of Šaušga. This may imply that Tudhaliya became the King of Hakpiš in his father's stead. Future generations were forbidden to take away the descendants of Hattušili and Pudu-Hepa from the service of Šaušga or to covet the cult's possessions. He also freed those future Priests from goods and labor obligations. Finally, he permanently elevated Šaušga's position in the royal cult by requiring his descendants who would later sit on the Hittite throne to be reverent towards her. A Palace Worthy of a Great King

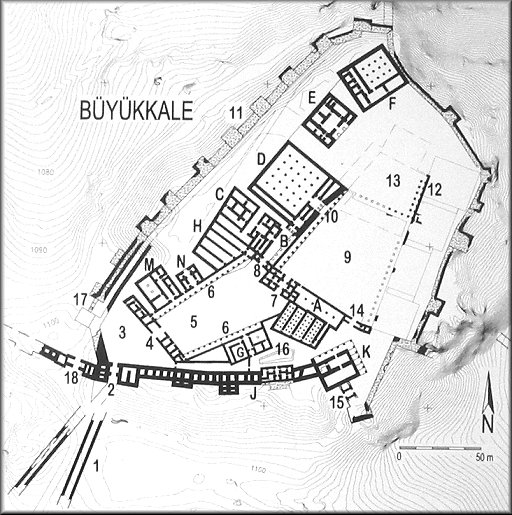

At least part of the palace on Büyükkale had been destroyed during Hattušili's struggle for the throne. Now that he was in possession of the capital as Great King, he took advantage of the opportunity and completely rebuilt the citadel plateau. On the east and west sides of the peak, which his grandfather Šuppiluliuma I had enlarged by means of man-made terraces, he built new terraces even further down the slopes of the hill (11). To the south, he did away with the last of the domestic buildings and now used the entire area for his palatial buildings. The entrance to the citadel in the southwest corner of the plateau seems to have been the most important. There were three gateways at this corner. On the western edge of this corner, a gate and a long, narrow ramp led down through the citadel wall to the Lower City (17). There was a spring at the base of the hill near this gate, which probably served as the citadel's source of water, as there isn't any in the citadel itself. Where the citadel wall met with the city wall, there were two gates: One gate opened from the Lower City to the exterior of the city wall (18), and the other, immediately to its east, opened from the citadel to the exterior of the city wall (2). Ramps led down to the lower level of the plain (1). This juncture seems to have served as the main entrence to the citadel , and when one entered into the citadel from this corner from either the Lower City or from outside the city walls one found himself in the Citadel Entrance Court (3), which had an irregularly trapezoidal shape. When you faced north, you faced a long, flat wall, which was actually the outside wall of the Southwest Hall. The hall was pierced by a main gate (4), which a walkway paved with red marble slabs led up to. If you went around this building's western corner, you would wind up in a sort of "service" area which ran all along the back side of the palatial buildings. To the east, a door blocked access to a long paved corridor which eventually opened up at a rather important looking water basin (16) which filled most of a courtyard surrounded by four buildings. Ritual objects have been discovered in this water basin, so at least one of the functions of this pool was religious. If you passed through the main gate in the Southwest Hall, you would find yourself in a large courtyard known as the Lower Court (5). This was surrounded by about half a dozen buildings of varying size. On the east side, two of these buildings opened up on their opposite side to the water basin. The building in the northwestern corner of this courtyard seems to have been some sort of storage facility (H). Two buildings adjacent to this (B, C) may have been shrines. Building C had a deep (2.3m) pool in its center, in which various ceramic vessels , believed to be votive offerings, have been discovered. The pool may have been open to the sky. Since these buildings were accessed from either the western service area or the Lower Court, and since this was the furthest court from the royal apartments, the Lower Court was probably an area for lower level court functionaries. One possibility is that the royal guard ("Golden Spear Men") resided here as well. On the northern face of the Lower Court was a gate (8) which led to a corridor which in turn led to the storage building and the service area. Next to that jutted out the Gate Building. By passing through this building (7), you found yourself standing in the Central Court (9). Here were the Audience Hall building on the west (Building D) and various other buildings whose remains are unfortunately very scanty. In addition to the Audience Hall, a significant cache of sealings were found in Building D. It seems that one of these (Building A) may have served as the royal archives, and at least some of these buildings served as stables. The courtyard with the water basin could be accessed from the southeastern corner of this court (14). Next to this was a large gate (15) with a broad ramp leading down and out of the city walls. An archive of tablets was discovered in Building K by this gate. It has been conjectured that chariots could have used this gate. All in all, the Middle Court gives the impression of being the place where the Great King could perform his royal duties. By passing through another gate one entered the Upper Court (13), the private domain of the Great King. It is a smaller, rectangular courtyard with a colannade surrounded by a handful of buildings. Only those on the western side are at all preserved. Buildings E and F are believed to have been the private apartments of the Great King of Hatti, with views over the city and across the valley. Building E also contained an archive of tablets. Either grain silos or cisterns seem to have been constructed on part of the eastern side of the courtyard (12). It is this version of the citadel which is best preserved and which can be seen when you visit the site today. Trouble in the West Hattušili's seizure of the Hittite throne left the Hittites' vassal kingdoms in an uncertain yet advantageous position. They were sworn to support the legitimate king, and to attack an usurper. If ever a vassal wished to throw off the yoke of Hittite rule, he was now presented with the perfect excuse to do so. But obviously, political realities and personal ambitions determined the actual position taken by each kingdom. Ahhiyawa, Hatti's rival for control of western Anatolia, would benefit from the coup more than any other foreign power, as it now found an opportunity to increase its influence in western Anatolia. Its policy seems to have been supremely and rather coldly influenced by its own ambitions. During the civil war, it had officially sided with Muršili, but apparently had failed to actually support him. While Hatti's resources were squandered on the war, Ahhiyawa could simply watch and wait. Muršili's defeat released Ahhiyawa from any friendly obligations towards the Hittite dynasty, and in fact it would have been entirely proper for Ahhiyawa to declare war against Hatti once Hattušili seized the throne. For Ahhiyawa, the civil war was win-win, and their subsequent actions reveal that they were not slow to take advantage of the situation. In the north the land of Wiluša seems to have slipped into the Ahhiyawan camp. In the far south the Lukka Lands seem to have fallen into general disorder. As in the north, it was the Ahhiyawans who benifitted. The Lukkans transferred their allegiance to a man named Tawagalawa, a brother of the King of Ahhiyawa. Here we find another possible connection with the world of the Homeric epics. It has been proposed, if not proven, that the name Tawagalawa(s) can be transformed into the name Etewokléwēs, i.e. Eteocles, a figure from Homeric tales, the son of Andreus, King of Orchomenos. While trying to directly equate Tawagalawa(s) with Eteocles is probably too much for the evidence to bear, it would not be unreasonable to draw an etymological connection between the two. There are two strong reasons to do so. Where the Greek language has an e-grade in many words, in Luwian we would not be surprised to find it in an a-grade, an argument which could be used to transform Etewokléwēs into Atawoklawas. Further, in the Luwian language, initial a's are frequently dropped, thus further transforming the name into Tawoklawas. From here, only a few more readily available arguments are needed to fully transform the Greek name into the form found in the Hittite document, Tawagalawa(s). But it should be noted that we have no reaseon to believe that a Hittite scribe hearing Etewokléwēs would ponder the neccessary transformations and then write the name down as Tawagalawa(s). The implication is that the Greek name had undergone this transformation over time, which means that we find ourselves with a Greek prince bearing a Luwian, or at least Luwianized, name. Whether he bore this name as some sort of Lukkan throne name, or whether it was actually his given name, we cannot know at this time. Under Tawagalawa's auspices, Lukkan warriors began attacking Hittite territory. In fact, Hattušili rapidly lost control of the situation, and Lukkan warriors burst into the Hulaya River Land. One of the Hittite border districts belonging to this land, that centered on the city of Hawaliya, rose in revolt along with the Lukkans at the frontier districts of Nataš, Parha (Cl. Perge in Pamphylia), Harhaššuwanta, and other lands whose names are only poorly preserved. Hattušili had now lost not only the Lukka lands, but his entire southern coast west of Kizzuwatna! These rebel lands invaded and conquered Hittite border territories such as Wašuwatta and Harputtawana. It seems that at this time there was little that Hattušili could do to stop them. This weakness, of course, opened the door for even further incursions. Either now or shortly in the future in connection with these raids, the Hittite's old enemy Piyama-radu reappeared and seems to have seen an opportunity to once again further his own interests at the Hittites' expense. Apparently based now out of the the city Millawanda, he began invading Hittite territory. Naturally Hattušili sent a messenger to Piyama-radu protesting his behavior. It doesn't seem to have accomplished very much, since someone, presumably Piyama-radu, went on to essentially conquer all of the Hulaya River Land, even managing to conquer at least part of the Lower Land and penetrate as far east as the land Nahita. All of southwestern and south central Anatolia had been lost to Lukkan raiders operating under Ahhiyawan auspices. At no other time in history had the Aegean kingdom's influence been felt so far eastward. The Lukkan reach now extended eastward even farther than the Arzawans had penetrated at the beginning of the reign of Šuppiluliuma I! Hattušili desperately needed to take control of the situation. Fortunately, Hittite might proved more formidable than the Ahhiyawans anticipated. Hattušili marched against the enemy and managed to push them back away from the Lower Land and at least regain control of a part of the Hulaya River, although he does not appear to have regained control of the coast. On the west, his borders at this time probably did not include the plain of Pamphylia. But it was a start, and Hattušili had other problems that he needed to concern himself with. Faced with the dilemma of how to reassert Hittite authority in the south and southwest while not devoting too much of his resources to the task, he apparently chose a solution that resembled the solution his brother Muwattalli had used to regain control of the northern Kaškan lands. Here in the south Hattušili created a vast new kingdom, that of Tarhuntašša, whose king would have the responsibility of using his own resources in the reconquest of the lost territories. The natural choice for the king of this new kingdom was Ulmi-Teššup, the son of Muwattalli II whom Hattušili had raised in his own household since childhood. So Hattušili secured a treaty with his nephew which gave a detailed outline of Ulmi-Teššup's borders and responsibilities towards the Great King. Ulmi-Teššup's borders with respect to the neighboring lands of Pitašša, Ušša, and Hatti were fairly well established, but his south and southwestern borders were more fluid, since Hattušili had not fully restored Hittite prominence in these regions. So Ulmi-Teššup was expected to expand his dominion in this direction, so that,

Although the course of subsequent events in Tarhuntašša remains somewhat vague, we do know the ultimate outcome. By the reign of Hattušili's successor, the borders of Tarhuntašša would be pushed south to the Mediterraenean Sea and west to the Kaštaraya River (Cl. Kestros) across from the city of Parha (Cl. Perge), deep into the Pamphylian plain, which was itself expected to fall into Hittite hands. Ulmi-Teššup would soon take on a second, non-Hurrian name which he would come to be better known by. Under the name of Kurunta, this son of Muwattalli would acquire prominence in the west which Hattušili would seek to use to his own advantage in his dealings with the kingdom of Ahhiyawa. Peace Among the Lands Having taken the imperial throne, it was now Hattušili's task to secure his position in the eyes of Hatti's foreign neighbors. In the east Hattušili made an effort to normalize relations with the rising power of Assyria. Messengers and goods seem to have passed between the two lands since at least the days of Muwattalli II. But there was the occasional glitch. Muršili III seems to have maintained his father's general antipathy towards Assyria, so when Hattušili seized the throne, it's perhaps not surprising that the Assyrian king, probably Adad-nirari I, failed to properly handle Hattušili's accsession. Not to mention that Hattušili's accession wasn't exactly regular. Either genuinely or strategically insulted by this, Hattušili presumed to give the Assyrian an etiquette lesson;

As a result of this social blunder, Hattušili detained the Hittite messenger to Assyria and his counterpart, the Assyrian messenger Bēl-qarrād. Nevertheless, Hattušili sought recognition, not war, and so he was not prepared to let the insult endanger his hopes for good relations. In fact he was willing to make some extraordinary concessions. To begin with, he sent out the requests that the Assyrian had already made. He further tried to assuage any fears that the Assyrian ruler might have that his messenger was being ill treated during his detention, and at the same time he managed to put in a plug against Muršili III,

If the scholarly textual restorations are correct, then the type of trade highlighted in this letter is interesting. The Assyrian king sought only one thing from his Hittite companion: iron. He requested "good iron", which Hattušili claimed was not available from his storehouse in Kizzuwatna because it was "a bad time for making iron". This may imply that iron working, still in its infancy, was a seasonal affair. It has been suggested, on comparison with other cultures, that Hittite iron working was a sort of cottage industry at this time. The Assyrian king had also sent suits of armor to the Hittite emperor, in return for which he expected "blades [of iron]". Again, it was Hittite iron that the Assyrians desired. More frustrating is the fact that we have no idea of the quantities of goods involved, which, in royal trade, could be either staggering large or just as surprisingly small. How many suits of armor did the Hittite king receive? How many iron blades did the Assyrian receive? Given the scarcity of iron, its value, and the fact that the technique of creating steel had not yet been discovered, we may hestitatingly suggest that this was the trade of prestige goods, to be distributed among the privileged classes, rather than basic equipment for war. After all, relations between the two lands were still in an awkward phase. Hattušili still carefully refrained from calling his correspondant "brother". But relations between the two lands were too important to him to disrupt. This same letter contains other strong evidence of the warming relations between these two distant lands and also how rapidly the Assyrian empire had grown under Adad-nirari's care,

The Assryian empire had grown so rapidly that Adad-nirari wasn't even certain whether or not Turira was a part of it! As for Hattušili, he was willing to let the Assyrian handle the problem himself, even though Kargamiš, his most important Syrian possession, was being continually attacked! Relations with Babylonia became even friendlier, although Hattušili initially had some problems in this area. Muršili, not content to remain passively on his estates in Nuhašši, planned to flee to Babylonia. But Hattušili discovered his plans and banished him to "the seacoast" (i.e. Cyprus? Helck, JCS 17, 38). Soon after, Hattušili was able to establish a relationship of brotherhood and aid with Kadašman-Turgu. One wonders if perhaps it was the King of Babylonia himself who exposed Muršili's plans. The new found brotherhood between these two kings was dramatically confirmed when Hattušili's initial relations with Egypt broke down. Someone who Hattušili refers to as "my enemy" escaped to another land and thence into Egypt. This "enemy" was almost certainly the deposed king Muršili III. Hattušili wrote to Rameses and demanded the extradition of his enemy, but Rameses refused. The result was inevitable: "[Because of this, I and the King] of Egypt became angry with one another." When Hattušili wrote to Kadašman-Turgu about these hostilities, he got a more enthusiastic response than he probably anticipated. The Babylonian king cut off the messenger of the King of Egypt and further promised,

But Hattušili was not prepared for anything other than a cold war with Egypt, and he never called upon the Babylonian king's promised aid. In fact, relations between the two lands were to turn for the better. Eventually, these feelings would blossom into the most famous peace established in the ancient world, where the two mortal enemies, Hatti and Egypt, finally resolved their differences in a manner which would ring down the ages to our own day. Peace in the West Hattušili's efforts at war in the western half of his empire finally stabilized the situation there. Kurunta, as King of Tarhuntašša, established himself as a ruler of some reputation in the west. The efforts of the Ahhiyawans to dominate there seem to have resulted in little success. Ultimately, they came to terms with Hattušili, and seem to have largely abandoned all their Anatolian aspirations. The dispute over Wiluša was resolved in Hattušili's favor, returning the land of the Trojans once more to the Hittite fold. In the south, Kurunta, acting on behalf of Hattušili, helped secure Hittite interests, and even met with the Ahhiyawan king in the city of Millawanda, one of the few Anatolian possessions which remained in Ahhiyawan hands. Little else did, however, and as the Ahhiyawans withdrew, the Lukka lands returned their allegiance to the Hittites. The withdrawal of the Ahhiyawans resulted in the scrambling of the local rulers to seek allegiance with the Hittites. Among these rulers was Piyama-radu, who had spent a good portion of his career waging war against the Hittites. Knowledge of his previous crimes against the Hittites seem to have stirred feelings of paranoia in him, and his actions became erratic. At first, like the other Lukkan leaders, he decided to swear allegiance to Hattušili. To this end, as Hattušili was riding to the Lukka lands in order to assert his authority in the region, he wrote to him in the city Šallapa,

Hattušili was willing, and so he sent the Crown Prince to Piyama-radu in the city Millawanda, still under Ahhiyawan control under the leadership of Piyama-radu's in-law Atpa, ordering him to ride back with Piyama-radu on a chariot. But by the time the Crown Prince arrived, Piyama-radu appears to have had second thoughts, and could not bring himself to trust his wellbeing to the Hittites. Further, it turned out that the Crown Prince was nothing more than a boy. Piyama-radu's confidence in Hattušili's sincerity evaporated. So, in spite of his earlier request, he now refused to ride into Hattušili's presence. It was a humiliation for the Crown Prince, and did little to endear Piyama-radu to Hattušili. But Piyama-radu was still willing to subject himself to the Hittites, as long as he could do so in friendly territory. So now he demanded,

Hattušili was still willing to continue negotiations with Piyama-radu, but his journey westward continued. He sought a sign of goodwill from Piyama-radu, and so when he reached the city Wiyanawanda, he wrote to him,

Piyama-radu agreed, but his word proved untrustworthy. As Hattušili approached Yalanda, Piyama-radu's brother Lahurzi ambushed him in three places. The terrain was difficult, and Hattušili had to approach it on foot, but even so he managed to secure victory for himself. Yalanda paid for Lahurzi's betrayal, and Hattušili ravaged it and took control of the city itself. From here he moved on to the city Apawiya, from which he wrote to Piyama-radu in Millawanda, ordering him to come to him. He also wrote to his new ally, the king of Ahhiyawa, protesting Piyama-radu's behavior and asking him whether or not he knew about it. The king's reply was not as friendly as Hattušili had wanted, as it included no greeting or gifts, but simply the bare statement by his messenger that,

He further gave Hattušili permission to bring Piyama-radu into his prescence, on the condition that he would not take him away. Hattušili agreed. Having gained the Ahhiyawan ruler's permission, Hattušili began his journey to the city Millawanda. At each stop along the way, he wrote to Atpa in Millawanda,

But these assurances were still not enough for Piyama-radu. The spectacle of the Crown Prince's journey weighed heavily in his mind, and Atpa wrote to Hattušili on his behalf, "Does My Sun give (his) hand to a boy?" It was an added insult to injury, and Hattušili indignantly replied,

Still expecting to resolve the matter, he promised that, if he should come to him, he would resolve all issues, and keep the king of Ahhiyawa informed of his comings and goings. Yet it was not enough. In spite of his growing annoyance, he was still anxious not to offend his new ally, and to keep his dealings with the Aegean king strictly on the up-and-up. So, he came to Millawanda to present his case against Piyama-radu, declaring,

One of these subjects was Tawagalawa, who came to Millawanda to meet with Hattušili on this occassion. Atpa also heard Hattušili's protests, as did another of Piyama-radu's relations, Awayana. But the presence of the Hittite Great King himself in the city of his refuge was too much for Piyama-radu to bear, and, declaring that he still feared for his life, he boarded a ship and sailed away. It was all becoming a little too much for Hattušili to bear, and his protests to the Ahhiyawan king became more strenuous,

Finally, Hattušili wrote directly to the king of Ahhiyawa about the matter. The letter took up fully three tablets outlining Piyama-radu's offenses and Hattušili's attempts to deal with him fairly. Only the last tablet has been discovered today. In spite of his growing frustration, Hattušili was still anxious to resolve the situation peacefully. Piyama-radu certainly still retained the favor of Atpa, and presumably the king of Ahhiyawa still supported him as well. So, in spite of Piyama-radu's growing offenses, Hattušili still attempted to bring Piyama-radu to heel through diplomacy. In his letter to the king of Ahhiyawa, Hattušili highlights the warm relations that now existed between their two lands,

If Piyama-radu failed to make such a promise, then Hattušili asked that the king of Ahhiyawa at least return the 7,000 civilian captives that Piyama-radu had taken from Hatti. Hattušili even agreed to establish a sort of panel which, under Ahhiyawan auspices, would take testimony from these civilians. Those who claimed they had fled from Hatti as fugitives would remain in Ahhiyawan territory, while those who had been taken by force would be returned to Hatti. Piyama-radu's activities could not be permitted to continue. Apparently, after he fled from Millawanda, he sought his fortune once again in the north, where he began raiding Hittite territory. This in spite of the peace established between Hatti and Ahhiyawa. Hattušili had difficulty believing that his brother would support such activity,

Obviously, Hattušili did not expect the king of Ahhiyawa to approve. Not shy about telling others what they should do, Hattušili suggested that, if Piyama-radu still wanted Hattušili as his lord, then his brother should write a letter to Piyama-radu with the following command,

The ultimate outcome of Hattušili's efforts is not, of course, preserved in his letter to the king of Ahhiyawa. However, we learn later, from Hattušili's son, that Piyama-radu apparently was extradited to Hatti. Whether his fate was for the better or the worse, his days of hostility against the Hittites seem to have finally ended. Eternal Brotherhood On the 21st day, of the 1st month of the winter season, in the 21st year of his reign (1259 B.C.), Rameses received in his capital city of Pi-Ramesse a distinguished party of visitors. Accompagning his own three Egyptian messengers came three Hittite messengers; the 1st and 2nd messengers of Hatti - named Tili-Teššup and Ramose, and the messenger of Kargamiš - named Yapušili. These messengers bore a silver tablet which was the Hittite version of a treaty of eternal brotherhood between the rulers of Hatti and the rulers of Egypt. It was the culmination of months of negotiation between the two rulers. Written in the Akkadian rather than the Hittite language, it presented the words of the treaty as if Hattušili were himself the speaker. Likewise, Hattušili received a version of the treaty written as if Rameses were the speaker. While treaties were common within the Hittite empire, they were foreign novelties in Egypt. Rameses took a great interest in this strange document, later inscribing the version he received from Hattušili on the walls of Karnak and at the Ramesseum in Thebes. The historical section of the treaties are unfortunately meager, and instead the treaties quickly move on to the establishment of brotherhood between the two rulers,

The treaty went on to cover topics by now familiar from other treaties. The two Great Kings agreed not to begin hostilities against each other or take anything which belonged to the other. A defensive alliance was set up in which either one of the Great Kings would himself come to the aid of the other, or that he would at least send troops. Interestingly, only Hattušili's sons were guaranteed support for when it was their time to come to the throne. Also of great interest are the provisions concerning the extradition of fugitives. In the cuneiform copies from Hattuša they appear as one long section of the treaty. But in the Egyptian version they seem to reveal their real significance. After the standard promise to return fugitives to each other's lands, the divine witnesses, curses, and blessings are recorded. These items normally indicate the end of the treaty. But after these items, another section pertaining to the return of fugitives is recorded. And the specifics of this section of the treaty are interesting. It begins with fugitives from Egypt, but the parallel and more historically significant passage from the Hittite perspective reads,

The fact that this was included after the normal conclusion to the treaty makes this seem like a special, last minute addition to the terms. It is generally suspected that there was one particular person in mind when this clause was written - Muršili III, currently residing in Egypt under Rameses' care. Since Muršili had fled to Egypt before the drawing up of the peace treaty, Rameses could hardly honorably agree to send Muršili back to Hatti only to be executed, which probably accounts for the extended description of how such a returned fugitive would be treated. Although Muršili might be seen to be excluded from the provisions of the treaty altogether, since his arrival in Egypt predated its formulation, Hattušili would nonetheless later use this clause in an effort to get Rameses to send the deposed ruler back to Hatti. The novelty of the treaty also expresses itself in the attention the Egyptians gave to the seals found on the treaty, which they described in detail,

It is easy for us to imagine the general look of the treaty. Land donations bore the king's seal in their middle dating back to the Old Kingdom. We have seen seals where the king is embraced by the god beginning with Muwattalli II, although this is the only evidence we have that Hattušili continued this practice. This also reveals that seals could be commemorated for specific events, something that we have not known before. From the Hittite point of view, there is also another extremely significant point. While the obverse contained a seal depicting Hattušili in the embrace of the Storm God, the reverse contained a seal depicting Great Queen Pudu-Hepa in the embrace of the Sun Goddess of Arinna. Here we see Pudu-Hepa prominently taking part in international relations of the highest order. Pudu-Hepa, although always officially subordinate to the Great King himself, would prove herself to be the real force behind the throne, as is revealed by the letters that passed between these two courts after the treaty had been made. Pudu-Hepa associated herself to all important documents of state. Even in the letters written to the Egyptian court, there were occasions when one letter was written by Hattušili and a matching letter was written by Pudu-Hepa. Likewise, both Hattušili and Pudu-Hepa could receive letters as well. But in truth, the families of both men became involved in this exhuberant good will. Egyptian and Hittite princes would write to their "fathers", Rameses' wife Nefertari wrote to Pudu-Hepa, and even the King of Mira wrote to Rameses. Each letter, of course, was accompagnied by sumptuous gifts - jewelry, gold cups, fine garments, linen clothes and bedspreads, and dyed cloaks and tunics. One of the Hittite princes to become involved in these exchanges was Tašmi-Šarruma, who may have been the future Great King Tudhaliya IV. But this newfound friendship wasn't quite everything that Hattušili seems to have desired. His nephew Muršili remained in Rameses' hands. Hattušili seems to have wanted him extradited under the terms of the treaty, but Rameses refused to budge on this point. Rumors about Rameses' intentions seem to have begun circulating. At some point, Kupanta-Kurunta, a true Methuselah who had been the King of Mira and Kuwaliya since the 12th year of Muršili II's reign, wrote to Rameses to confront him about these rumors. Rameses' reply seems to have been sent to the Hittite court, where his reply letter was found. Why a vassal king was corresponding with the pharaoh about affairs of state remains a mystery to us, although at his age Kupanta-Kurunta may have been held in the very highest of regard. There is no mystery, however, in Rameses' reply,

But it was not only Kupanta-Kurunta who had been pressuring Rameses,

To all of these rumors and demands, Rameses replied, "What have I done? Where would I recognize Urhi-Teššup (as ruler)?", and offered the stern opinion that, "[The word] which men speak to you is worthless. Do not trust in it!" (HDT #22D). Both Hattušili and Kupanta-Kurunta seem to have viewed Rameses' reluctance to return Urhi-Teššup as a violation of the terms of the treaty, which Rameses vigorously denied, reiterating that he had taken the oath of brotherhood and good relations and that he intended to stand by it. There was also the issue of Rameses overbearing tone in his letters. The god-king was unaccustomed to having equals, and his haughty words ruffled Hattušili's feathers, "Why did you, my brother, write to me as if I were a subject of yours?" (Kitchen (1982) 82). Rameses protested to this as vigorously as he did to the other accusations,

In spite of these sensitive subjects, relations between the two courts continued to warm over time. It was just as well for Hattušili, since the situation in Babylonia soon deteriorated upon the death of his ally Kadašman-Turgu. After an appropriate mourning period in which Hattušili "wept for him like a brother", Hattušili dried his tears and fulfilled his treaty obligation, writing to the Babylonians,

But the new king, Kadašman-Enlil II, was only a minor. His vizier, Itti-Marduk-balatu, did not take kindly the Hittite king's interference, and leveled an accusation against Hattušili which probably sounded a lot better to Hattušili when he had been the one making it,

So relations with Babylonia became strained. It's also around this time that relations with Assyria fell apart, although the particular causes are not known. In all likelihood the problem was caused by disputes over what was left of the once mighty Mitanni. Sometime shortly before the death of Adad-nirari I, Mitanni appears to have freed itself from its Assyrian overlord. Whether this was with Hittite aid is unknown, but this land clearly moved over into the Hittite camp. The bad relations that this caused between the two lands seems to have remained for the rest of Hattušili's reign. Once Kadašman-Enlil of Babylon came of age, Hattušili tried to mend the breach between their two lands. He wrote to the Babylonian Great King telling him how he had tried to support him when he was first raised to the throne, and how his actions were misinterpreted by Itti-Marduk-balatu, an "evil man" whom "the gods have caused to live far too long." He was also concerned about the interruption of messengers from Babylon - a sign of hostility - on account of the Ahlamu, a people who would one day come to play an important role in Near Eastern history. Hattušili could not believe that they were the real reason that messengers no longer came to Hatti, "Is the might of your kingdom small, my brother? Or has perhaps Itti-Marduk-balatu spoken unfavorable words before my brother, so that my brother has cut off the messengers?" If the Ahlamu weren't excuse enough, Kadašman-Enlil stalled further by bringing in the Assyrians, too, "The King of Assyria will not allow my messenger [to enter] his land". Hattušili wasn't any more willing to accept that excuse,

Hattušili took several steps in an effort to placate his reluctant ally. He assured him that he had no reason to object to messengers passing back and forth between Babylonia and Egypt. He made arrangements to deal with various legal disputes, one of which involved Bentišina, King of Amurru. He spoke of the death of a Babylonian physician who had come to live in Hatti and who had married one of Hattušili's own relations. Having heard that Kadašman-Enlil now regularly went out on hunt but not for war, he encouraged the young king to "go and plunder an enemy land in this manner so that I might hear about it." Hattušili never names a specific land against which he wanted the Babylonian to march, but when he encourages Kadašman-Enlil to "go against a land over which you enjoy a three- or fourfold numerical superiority," it sounds suspiciously as if Hattušili is hinting at Assyria. The remainder of the letter deals with requests for a sculptor, stallions which are taller than the ones sent by Kadašman-Turgu, particularly foals, since old horses could not survive the harsh winters in Hatti, and silver. All these efforts seem to have eventually paid off. Relations between the two lands were fully normalized, and at some point Hattušili sent one of his daughters to Babylonia to marry the Babylonian Great King, and he himself married a Babylonian princess. And what better way to demonstrate friendship and brotherhood could there be? Such a marriage generated great esteem. And if it could work with Babylonia, what about an even more important neighbor? A Royal Wedding Hattušili's relations with Egypt continued to become closer and closer. The correspondence between the two kings eventually turned to matters of a marriage between one of Hattušili's daughters and Rameses. It was to be a wedding beyond compare. So it was that in the 33rd year of Rameses' reign, Hattušili promised Rameses that "greater will be her dowry than that of the daughter of the King of Babylon, and that of the daughter of the King of B[arga(?)] ... This year, I will send my daughter, who will bring servants, cattle, sheep, and horses to the (Hittite border)land of Aya". At Aya Rameses arranged to have a man named Suta, the governor of Kumidi in Apa, receive "these Kaškan slaves, these droves of horses, these flocks and herds which she will bring". From there Suta would escort the bride to Egypt. But after this, delays occured on the Hittite side. After having made such extravagent promises concerning the size of the princess's dowry, the Hittites had some trouble gathering everything together. This delay pulled out an irritated response from Rameses, to which Pudu-Hepa replied with an equally irritated defense. She claimed that a daughter could not be sent at this time because the storehouse of Hatti was "a burnt out structure", and that Urhi-Teššup had given what remained to "the Great God". If Rameses did not believe her, then he could ask Urhi-Teššup himself, since he was still there in Egypt. Rameses' blatant desire for the Hittite princess's goods did not sit well with Pudu-Hepa, either,

Bureaucratic snafus had also delayed things until winter came and put everything on hold. Nevertheless, Pudu-Hepa promised that the marriage party would move down as far as Kizzuwatna where they would pass the winter. Pudu-Hepa herself had plans to visit Amurru, from which she would write to Rameses. We learn incidentally from another letter from Rameses to Pudu-Hepa that Tili-Teššup and Ramose, the 1st and 2nd messengers of Hatti who brought the silver treaty tablet to Rameses thirteen years earlier, were still the Hittite messengers to the Egyptian court, where they now carried on the correspondence dealing with the royal marriage and other matters. One of these involved the sons of a man named Mašniyalli, Hittite subjects who were currently residing with Rameses in Egypt. Tili-Teššup was told that these two sons were to return to Hatti, but Ramose was not given this message. In fact, no one but Tili-Teššup seems to have been aware of this order. While Rameses was still willing to send back the boys with Tili-Teššup, now it was Tili-Teššup who balked, saying, "No, I will not take them until the tablet of the Great King, the King of Hatti, together with the tablet of the Queen, arrives, saying 'Send them!'" So Rameses duly requested that Pudu-Hepa send clarifying instructions. The following spring, in Year 34 of Rameses' reign, Hattušili set in motion the marriage procession, writing to Rameses, "Let people come to pour fine oil upon my daughter's head, and may she be brought into the house of the Great King, the King of Egypt!", to which Rameses replied, "Excellent, excellent is this decision about which my brother has written to me... the two great lands will become as one land forever!" Probably that autumn, the Hittite princess crossed over from Hittite territory into Egyptian territory, perhaps bidding farewell to the Great Queen in Amurru. About February of the the next year (still the same year by ancient reckoning) she arrived at the Egyptian capital where she was duly wedded to Rameses II, Great King of Egypt. Her trip had been a pleasant one, and Rameses was not reluctant to take the credit:

Their arrival in Egypt heralded a new age of unprecedented peace that echoed out to the petty chiefs of Palestine,

As usual, humility was nowhere to be seen where Rameses was involved. Rameses proclaimed the princess's beauty and how he loved her more than anything else, and we may presume that the wedding got off to a happy start. The wedding was even more prominent in Rameses' inscriptions than the earlier treaty, with copies of a special commemorative inscription being carved in Karnak, Elephantine, Aksha, Abu Simbel, and Amara West. The following year the happy occassion was still strong in Rameses' mind. Another inscription was written to accompagny the marriage inscriptions which spoke of the unprecedented peace that existed between Egypt and Hatti. The new queen resided with her husband at Pi-Ramesse where her name was carved on its monuments. But eventually, as she aged, so would her popularity with the pharaoh, until finally she would be sent to reside at the harem by the Fayum garden province, some 120 miles away from Rameses' capital city. But for now all was goodness and brotherhood. Not only did messengers pass to and fro between the lands, but soon royal personages also began to make the journey. Even Hešmi-Šarruma, the later Great King Tudhaliya IV, travelled to Egypt, choosing to set out, like his sister before him, in the winter months. It seems that even the Hittites were interested in warmer climes during the harsh Anatolian winter. What impression Egypt had on the future king is not known, although it has certainly been speculated about. The Happy Correspondence (This situation is not likely to remain. I just wanted to get the passage about Kadesh in here. As I translate the letters and work out a chronology for them of some sort, then I will likely find a better arrangement.) While relations between Hattušili and Rameses continued warmly over time, they did not always agree about everything. It seems that Hattušili had come to hear about Rameses' portrayal of the events which took place at Kadesh, and took exception his depiction of them. He brought up his objections to his ally, but Rameses was not about to back down from his own official version of history,

Then followed a more detailed recounting of Rameses' version of the battle, which agrees with the events as depicted by the pharaoh in his other works on the subject. Not even for a man who had been a witness to the events would Rameses dilute his propaganda! A Royal Trip to Egypt The Egyptian and Hittite rulers seem to have enthusiastically embraced their friendship, particularly Rameses. At some point he even invited Hattuš ili to come and visit Egypt so that they could actually meet each other. Hattušili's reply was less than enthusiastic, "May my brother write and tell me just what we would do there!" But Rameses was persistant, and he offered to meet Hattušili in Canaan, and then to escort him to his capital at Pi-Rameses. A problem (real or feigned) with Hattušili's feet delayed the trip, but ultimately Hattušili did indeed set out for Egypt, to meet with Rameses. The last time these men had met was in the field of battle, when Hattušili was only an officer in the army of Muwattalli II. Now he was Great King, and he met Rameses in peace. The Desire for Egyptian Know-how The Hittites seem to have been in constant need of foreign doctors with greater medical know-how than their own. When Kurunta, King of Tarhuntašša, fell ill, a physician by the name of Pariamahu was sent to prepare herbs for him. This was not Pariamahu's only trip, and on one occasion two Egyptian doctors returned as he was sent out. Hattušili's faith in the powers of Egyptian physicians was a little excessive. He wrote to Rameses requesting a physician who could enable his sister Maššanuzzi, the Queen of the Šeha River land, to bear children. Rameses reply was frank,

Nonetheless, Rameses duly sent forth a physician, along with his best wishes for success. Famine Relief from Egypt Some time after the treaty was concluded, Egypt sent grain to Hatti to relieve a famine (CTH #165, see Klengel (1974) 167 w/ n. 13). Another Marriage At some point in time Hattušili sent a second daughter to Egypt to marry the elderly pharaoh. The so-called "Marriage Stela" shows Hattušili himself handing over his daughter to Rameses. We know little about this marriage, only what Rameses put on his inscriptions. The date is unknown, but probably occurred during the forties of Rameses' regnal years. Close of an Era The close relations with Egypt probably continued for the rest of Hattušili's reign. At some point, the crown prince Tudhaliya appears to have become some sort of co-regent with his father. Since Tudhaliya himself had visited Egypt, we may suppose that the friendship and brotherhood created by Hattušili continued much the same in his son's reign. But we do not have any of the correspondence, and Egypt largely disappears from the Hittite historical documents. New generations were taking control in both lands, and the novelty of the situation might have simply worn off. In spite of this, there is nothing to indicate that the peace established by these two long-lived rulers was ever broken again. Relations with the West: Gifts exchanged with Ahhiyawa. Arzawa freed itself, probably during the civil war between Hattušili III and Muršili III. Fighting in the Lukka-Lands. Šeha River Land, after supporting Hattušili in the civil war, became a loyal vassal. Pudu-Hepa: Pudu-Hepa was the most powerful of the Tawannannas. Royal correspondance was regularly sealed with both her name and Hattušili's. She would also seal correspondance with only her name. There is a group of correspondances between Rameses II and her (CTH #158, #164 (Rameses to Pudu-Hepa), #160 (Pudu-Hepa to Rameses, see translation by SRT)), Rameses II and her together with Hattušili III CTH #159 (Rameses II to them both?), #162 (Rameses II to them)), and Rameses II and Hattušili III (CTH #157 (Rameses II to Hattušili III)), concerning the wedding arrangements between a Hittite princess and Rameses. There is also a letter from Rameses's wife to Pudu-Hepa (CTH #167), and another one which was written by Rameses's mother (CTH #168). The reason for Pudu-Hepa's deep involvement in Hittite politics (other than her strong character) might be related to the fact that Hattušili often seems to have fallen ill. A prayer made by Pudu-Hepa on behalf of her sick husband can be found in ANET, pp. 393f. Foreign Relations Amurru: Bente-šina re-installed as king of Amurru. Arzawa: Mašturi, king of the Šeha River Land, became a Hittite vassal. Hattušili campaigned in the Lukka Lands. Kaškans: Still causing difficulties. Hattušili campaigned against them for 15 years, while his son, as a general, campaigned against them for at least 12 years (CTH #83, CAH 2.2 p. 260). Tarhuntašša: Kurunta, son of Muwatalli II, was installed in Tarhuntašša (CTH #97) because he had sided with Hattušili in his war against Muršili III. |

|

| Some or all info taken from Hittites.info Free JavaScripts provided by The JavaScript Source | |